Albert McQuarrie: Thatcherite known as ‘the Buchan Bulldog’ for his staunch defence of Scottish fishing industry

McQuarrie spent much of his time as a consultant, carrying out development projects in the building industry

So devoted was Albert McQuarrie to Margaret Thatcher that he pursued her at every possible opportunity. On one occasion, at a Conservative conference in Scotland, he followed her into the ladies’ toilet. “No, Albert,” she intoned in her familiar way, “this is one place where you cannot follow me.”

This story – which is not apocryphal – is but one of the cascade of McQuarrie stories that added to the gaiety of the House of Commons village. That he got away with an assortment of enormities can be attributed to the fact that Albert – everyone, down to the newest doorkeeper, knew who “Albert” was – did not have a ministerial job in his sights. McQuarrie just wanted to make his point – usually, though not always, a sensible point. He was not an eccentric; he was not a maverick; he was a Parliamentary original. In his character, any sense of embarrassment was non-existent. When others might have blushed, McQuarrie would just produce a broad smile and a chuckle.

He was the son of Algernon McQuarrie, a Greenock shipping businessman. After Greenock High School, he went to the Royal College of Science and Technology, but immediately volunteered when war was declared in September 1939. Ever courageous, he became a bomb disposal officer in the Royal Engineers.

Posted to Plymouth, he worked hazardously through the Devonport Blitz, and in the aftermath of the Baedeker bombing at Exeter. In 1942, he was among a handful of fellow sapper officers and warrant officers thanked personally and individually for their work at Avonmouth docks.

McQuarrie’s first foray into Parliamentary politics could hardly have been more challenging. Willie Ross, the son of an Ayrshire railway guard, had been a Kilmarnock MP since 1945, when he had campaigned as Major Ross of the Highland Light Infantry. By 1966 he had been Secretary of State for Scotland for two years and one of Harold Wilson’s most valued Cabinet colleagues. The result – 26,036 votes to Ross, 11,949 to McQuarrie – hid the fact that McQuarrie was the only candidate in Scotland to reduce a Labour majority.

In 1970 and February 1974, McQuarrie looked in vain for winnable Tory seats, a scarce commodity in Scotland by that time. In any case, he was fully committed as chairman of A McQuarrie and Son, a successful company of builders and suppliers in the North-east of Scotland. In October 1974, out of duty to the Conservatives, he reluctantly agreed to be standard-bearer in Caithness and Sutherland against the up-and-coming Labour minister, Robert MacLennan. Finishing a distant fourth, he resigned himself to never entering Parliament. But in 1978 a feisty candidate was required to fight the SNP’s pugilistic Douglas Henderson, who had won the East Aberdeenshire seat in 1970, and McQuarrie fitted the bill.

Throughout the campaign he invoked memories of, and comparisons with, the well-remembered Bob Boothby, who had represented the area, with its important fishing ports of Fraserburgh and Peterhead, and when McQuarrie narrowly won – 16,827 votes to Henderson’s 16,269 – like Boothby he would, for the next eight years, extol the advantages of eating kippers at every appropriate (and inappropriate) opportunity. Following a boundary adjustment he represented Banff and Buchan, and become known as “the Buchan Bulldog” for his ferocious defence of Scottish fishing.

Huge dissatisfactions with the EU Common Fisheries Policy contributed to McQuarrie being one of the few Tories to lose his seat in 1987; His opponent, a Royal Bank of Scotland economist named Alec Salmond, was an excellent campaigner, exploiting every possible discontent, real or imaginary.

In the Commons, Gibraltar had no more doughty champion than McQuarrie. I well remember his fierce question to Geoffrey Howe on 24 October 1984: Howe had just returned from a difficult meeting of the EEC Foreign Affairs Council. “When the Foreign Secretary was with the Spanish Foreign Minister,” boomed McQuarrie, “did he discuss with him whether the Lisbon Agreement, which was signed on 10 April 1980, would be implemented? Did he tell the Foreign Minister that there is no question of Spain being allowed to enter the European Community so long as the restrictions on the border continue against Gibraltarians and British citizens?”

Telling McQuarrie that he was “rightly, continuously astute on this matter”, Howe went on to make an emollient answer – a wise response whenever McQuarrie was on the warpath.

McQuarrie told me some years later, “the loss of my seat, due to tactical voting and protests about the Poll Tax, was a big disappointment. Even with an increase of almost 1,000 votes over my 1983 victory result, the protestors won the day. I was sorry to have lost my seat in this manner, as I had worked hard as an MP.”

I know at first hand, from visits to the Peterhead Labour Party, that he had their respect for diligently applying himself to the problems of constituents who, he must have guessed, had no intention of giving him their vote. He ruefully recalled to me, “In 1985 I told Margaret Thatcher that we would lose our seats, but she said, ‘Oh, no, Albert, that can’t happen.’” In the event Tories were annihilated in Scotland.

In 1989 McQuarrie bravely agreed to stand in the Highlands and Islands, one of eight Scottish constituencies in the election for the European Parliament. He was trounced by Winnie Ewing – “Madame Ecosse”, as her colleagues in Strasbourg dubbed her.

Remarkably, as a mid-nonagenarian, McQuarrie spent much of his time as a consultant, carrying out development projects in the building industry – “This keeps my mind and body active,” he told me. Until recently, as the oldest member of the Association of Former Members of Parliament he was a regular attender of meetings in the Commons and a contributor to the Association’s magazine Order, Order. He told all and sundry that he enjoyed watching proceedings in Parliament on television, usually adding, “Often, I wish I was there in person.” I, for one, wish he was, too. µ TAM DALYELL

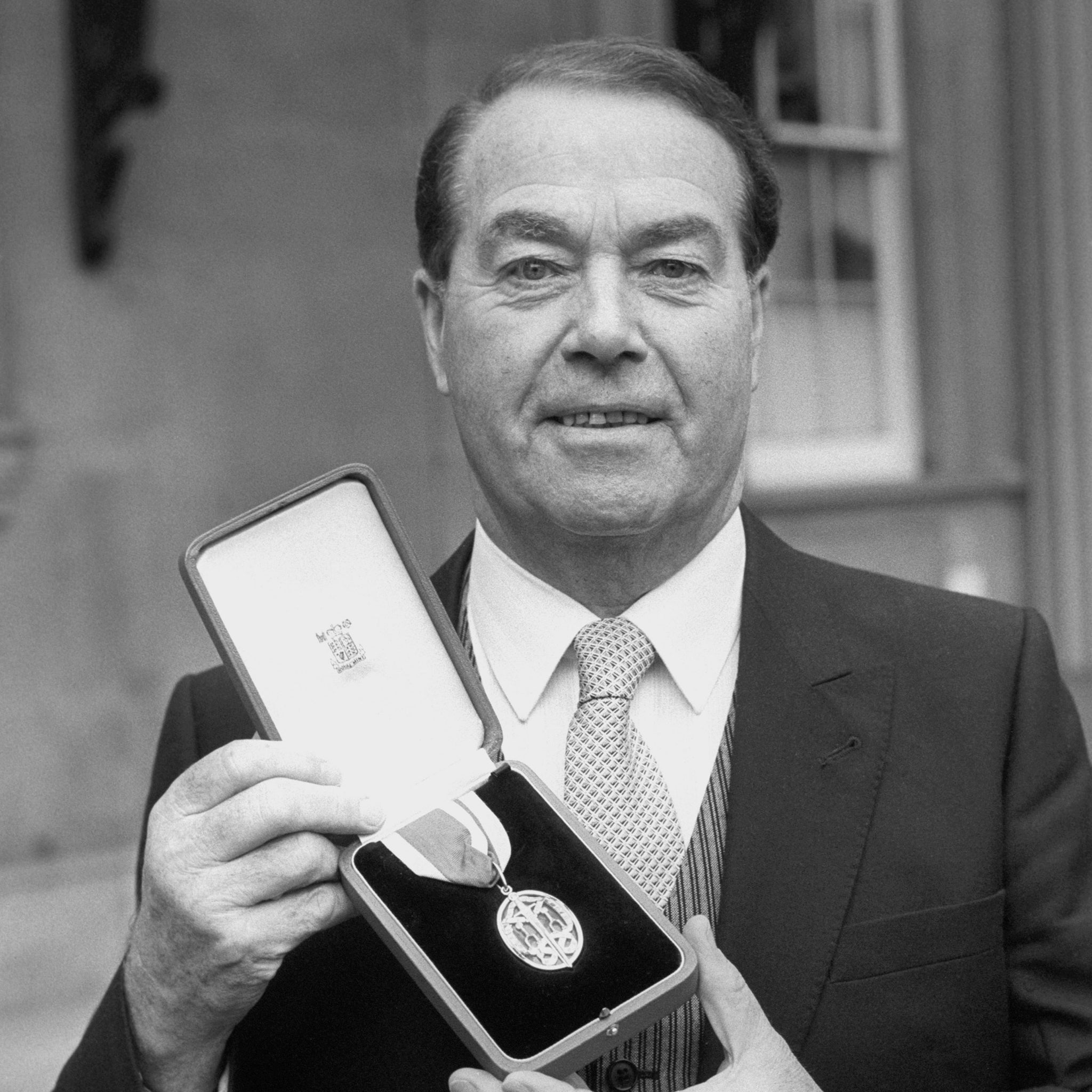

Albert McQuarrie, politician: born Greenock 1 January 1918; MP for Aberdeenshire East 1979–83, Banff and Buchan 1983–87; Kt 1987; married 1945 Roseleen McCaffery (died 1986; one son), 1989 Rhoda Annie Gall; died 13 January 2016.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments