Ernie Terrell: Boxer who won a world title but suffered a savage beating after inadvertently calling Muhammad Ali Cassius Clay

In every round, Ali would ask, 'What’s my name?'

When Ernie Terrell signed a contract to fight Muhammad Ali in 1967 he made an honest and understandable mistake and called his former friend, roommate and sparring partner Clay and not Ali. Terrell and the then Cassius Clay had shared rooms, rings, gyms in Miami and long car journeys in the early 1960s when they were both young prospects in the heavyweight business. They had lounged on idle afternoons talking about religion and politics in one of Miami’s two black-only hotels.

"I had only known him as Cassius Clay," Terrell told me one day in Las Vegas. "It was not an intentional insult, nothing that I planned, but I saw how he reacted and I just kept on calling him Clay." At the same time the US government, which was desperate to get Ali inducted into the army, also called him Clay, as did most of the British and American press.

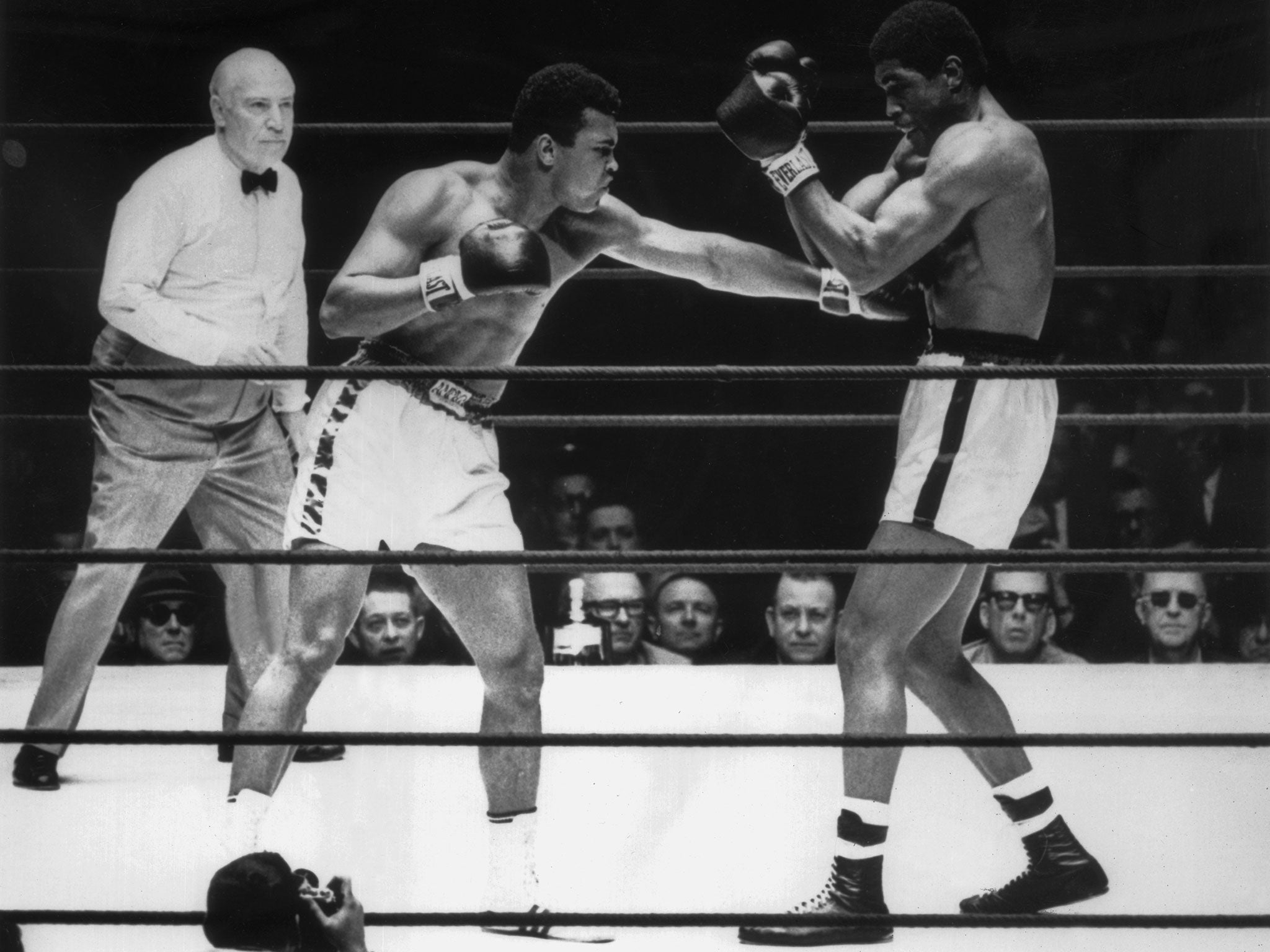

Ali was vicious in the build-up to their unification heavyweight championship fight at the Astrodome in Houston, Texas, and called Terrell a series of disgraceful names; in the ring the verbal savagery continued but was surpassed by what many considered to be the most appalling and deliberate beating ever seen in a title fight. It was also a brilliant display from an angry Ali.

Terrell had won the WBA version of the world heavyweight title in 1965 and had defended the championship twice before finally, at the second attempt, agreeing terms to fight Ali. A planned fight in 1966 in Chicago, where Terrell had lived since leaving his rural Mississippi home as teenager, had been scrapped by the Illinois Attorney General, William Clark. The pair, according to Clark, violated various trivial state laws but in reality Ali’s increasingly militant anti-Vietnam war stance was slowly reducing the available cities for him to continue fighting in.

In Houston a crowd of 37,321 gathered inside the gleaming arena to witness the darkest side of Ali’s perfected arts – it is a side denied by too many but it is impossible to ignore what the great champion did to Terrell that evening under the neon; it was also considered to be a real test for Ali as Terrell was taller and had beaten the best in the division.

"We had known each other a long time and had shared a lot of experiences," Terrell said. "I remember one time we drove from Miami to his home in Louisville and on the way we stopped at an all-black college; he was preaching to the students. He asked them: 'What country is called Negro?' And somebody said: 'I don’t know, but I never heard of a country called 'White Folks' either.' He never liked that."

In Houston during the intense build-up there were men who had called the fight "The Battle of the Century", and most ringside experts expected Ali to be tested against a man that he had dubbed The Octopus; it was, however, no pantomime of innocent, comical name-calling.

Terrell had not lost for five years and that defeat, to Cleveland Williams, was understandable as Williams remains one of the most avoided boxers in history. Terrell was in the fight for a round or two, able to jab, hold and move. However, Ali had an evil plan and each round he continued to ask the question: "What’s my name?" Terrell never replied, just taking a slow beating, but it was not Ali’s fists that damaged the big man from Chicago in what, in many ways, was a night of shame for the dirty old game.

Ali rubbed Terrell’s eyes along the ropes, stuck a thumb in the left eye and, at the start of the 13th round, spat at Terrell’s blood-stained boots. "What could I do?" Terrell asked. "I could not quit and that meant I had to keep fighting – I could see two or three of him because of the damage and trust me, one is enough."

At ringside the great sage of British boxing, George Whiting of the London Evening Standard, marvelled at the barbarity he was witness to: "Clay sneered and snarled and taunted, an even on one occasion, spat at the feet of the poor wreck of a Terrell."

Even Ali’s greatest defenders fall silent when the 15 rounds in Texas against Terrell is mentioned. Whiting, I should add, also described Ali as excellent.

Ali took the decision at the end and Terrell left for hospital. Terrell finally quit the ring in 1973 and became a powerful figure in his adopted home town of Chicago. He worked as a boxing promoter and then ran a large janitorial company. He also had some success as a singer and songwriter – his sister, Jean, replaced Diana Ross in the Supremes.

"We are friends now, good friends," Terrell insisted whenever he was asked about Ali. I have seen it, and I believe it, but what happened in the Astrodome ring will never be forgotten. On that night Big Ern, as Whiting called him, met the greatest heavyweight ever at the very peak of his powers. Ali would never be that good again and, sadly, Terrell would never be the same again.

Ernest Terrell, boxer: born Belzoni, Mississippi 4 April 1939; died Evergreen Park, Illinois 16 December 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments