Gough Whitlam: Charismatic and abrasive politician who was undone by the biggest constitutional crisis in Australia's history

Born in Melbourne, Whitlam grew up in Sydney until the transfer of federal parliament to the new capital resulted in his family moving to Canberra

Gough Whitlam, one of Australia's best known prime ministers, was in office for only three years, but was his country's most controversial and influential political identity for a decade. As prime minister he made at least as striking an impact as either of his two successors, Malcolm Fraser and Bob Hawke, although their terms were much longer than Whitlam's.

Assessments of Whitlam's impact vary. Because Australia had never known such a wholeheartedly reformist prime minister, it was not surprising that he was loathed and feared by conservatives (who tended to keep to themselves their admiration for his articulate stylishness). But he was a heroic figure to many Australians – younger voters especially – who felt that after a generation of conservative rule their country needed the programme of reform which his Labor government so purposefully tried to implement. However, some Labor enthusiasts were critical of what they saw as its naive zeal and political amateurishness.

Born in Melbourne, Whitlam grew up in Sydney until the transfer of federal parliament to the new capital resulted in his family moving to Canberra, where his father was deputy Crown Solicitor. From his parents Whitlam acquired a taste for intellectual pursuits and a predilection for precise speech. He followed his father into the law, interrupting his course during the Second World War to serve in the air force as a navigator. He joined the Labor Party in 1945.

From the moment he entered federal parliament in 1952 he stood out. Tall and confident, the 36-year-old barrister had a brilliant mind, a dazzling wit and a willingness to flaunt both.

His maiden speech highlighted the difficulties with housing and other amenities faced by residents in the outer suburbs which developed rapidly in Australia's largest cities after the war. These problems proved an enduring preoccupation. Labor's long spell in the wilderness after 1949 frustrated him, but it assisted his ascent. Becoming deputy leader to Arthur Calwell in 1960, he succeeded him after Labor's devastating defeat at the 1966 election.

His rise was a product of sheer ability. He shunned calculated friendships and factional support and throughout his career often treated colleagues with abrasiveness and contempt. He became the most brilliant opposition leader Australian politics had seen. Bold and resourceful, he modernised his party's structures and policies while mastering a trio of Liberal prime ministers. His willingness to stake all in daring manoeuvres was epitomised in a later comment which became a personal testament: "When you are faced with an impasse you have got to crash through or you've got to crash."

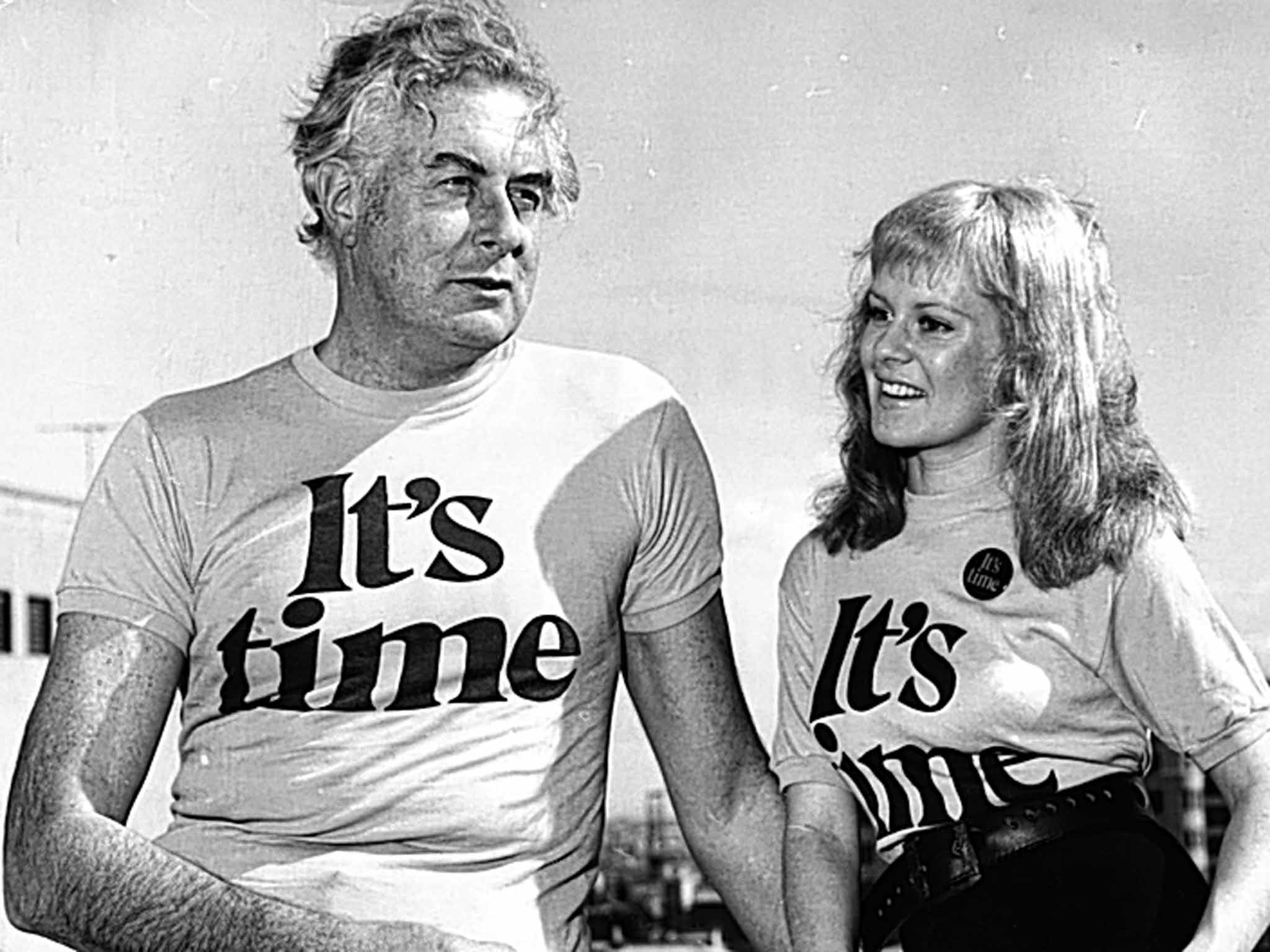

After a huge swing at the 1969 election almost carried Labor to victory, success came in 1972 after Whitlam spearheaded the memorable "It's time" campaign. The new government made a stunning start. The Labor custom that the parliamentary party elects the ministry together with other necessary formalities meant that a cabinet could not be assembled for weeks; Whitlam was so impatient to begin that an interim administration comprising himself and his deputy was sworn in to initiate the avalanche of change outlined in his policy speech.

For three years the pace of reform remained hectic, Whitlam devoting particular attention to education, health and community services. He was also vitally interested in foreign affairs, and ensured that nations previously oblivious or contemptuous of Australia became aware that it was now led by a progressive government. His vigorous support for the arts sparked a national cultural renaissance.

After being accustomed to a staid and insular national government for so long, many Australians felt uplifted. However, the government's helter-skelter approach to alleviating the neglect of decades not only led to some ill-considered decisions; it left no time for adequate consultation, explanation or promotion. Whitlam seemed not to grasp or care that while the dizzy pace of change excited and exhilarated some, more were alarmed and alienated.

Whitlam's sense of priorities was instrumental in another of his government's crucial shortcomings, economic management. Influenced by Australia's easy economic growth during the 1950s and '60s, Whitlam regarded monitoring the economy and making adjustments to it as tasks for lesser minds; the real creative challenge, he believed, was to formulate imaginative ways to redistribute Australia's wealth.

Accordingly, when his government encountered severe economic difficulties (mostly not of its own making), he was ill-equipped to deal with them. As inflation and unemployment grew, Whitlam's admirers applauded his insistence that economic problems were no alibi for slackening the momentum, but his detractors concluded that his priorities were askew.

Fundamental to Whitlam's approach in office was his concept of his mandate from the electorate. He regarded it as a sacred contract which obliged his government to implement all the reforms outlined in the policy speech. When cabinet made a decision that honoured a particular commitment Whitlam would often reach for his copy of the policy speech and tick the relevant item with a satisfied flourish.

But his commitment to reform generated virulent opposition. Conservatives and defenders of vested interests resorted to desperate and unscrupulous tactics. They used their majority in the Senate to block the supply of money to a prime minister with a majority in the lower chamber twice in 18 months.

On the first occasion Whitlam responded by dissolving both houses. His government was returned in the lower house but narrowly failed to secure a majority in the Senate. When supply was blocked again in October 1975, the government's popularity among uncommitted voters was low owing to a series of administrative "scandals" (notably the "loans affair", an unsuccessful attempt by the government to borrow an immense sum from unconventional international financial sources) as well as the ailing economy. This time he refused to call an election, opting to "tough it out." During the ensuing constitutional crisis Whitlam was at his inspirational best as he tried to intimidate the opposition into an ignominious backdown.

The deadlock lasted four weeks. At no other time have Australians followed a political confrontation more attentively or more passionately. Whitlam seemed on the verge of "crashing through" – with opinion polls showing strong support – when the Governor-General Sir John Kerr made a sensational intervention on 11 November, ordering an election.

Being dismissed by the Governor-General he had appointed was the biggest shock of Whitlam's life, Kerr had hidden from Whitlam his view that the Governor-General was no mere ceremonial figurehead, and about his particular intentions in the crisis. There have been assertions that foreign surveillance agencies were involved in Whitlam's dismissal; CIA sources have confirmed that their alarm about developments in Australia was conveyed to Kerr, and it has been claimed that British intelligence services were used to relay the message to him.

Whitlam's response was characteristic. "Well may we say 'God save the Queen' because nothing will save the Governor-General," he declared on the front steps of Parliament House in a fiery impromptu speech which generated the most memorable images of that remarkable day. He also referred to the new prime minister, Fraser, as "Kerr's cur" and exhorted ALP supporters to "maintain your rage and your enthusiasm... until polling day."

Whitlam's campaign rallies were massive and fervent, but swinging voters tended to see the constitutional issue as resolved by Kerr's action and voted on other issues. Labor was routed. Whitlam stayed on as opposition leader but was no longer the same formidable and confident figure. When Labor suffered another rout at the 1977 election he retired from parliament.

He became an ambassador to Unesco, but his most significant activity was writing. After Kerr published his self-justifying Matters for Judgment Whitlam wrote a witty rejoinder, The Truth of the Matter, and followed it with the massive The Whitlam Government 1972-1975.

Gough Whitlam's commanding presence and intellect made him a towering figure. The vicissitudes of his adventurous government will always be seen as a stirring era in Australia's history, when his vision, verve and brilliance in the public arena won him the veneration of hordes of admirers. His death and the inevitable spate of media retrospectives will unleash waves of nostalgia in the minds of many Australians who idolised him during the most politically animated time of their lives.

Edward Gough Whitlam, politician: born Melbourne 11 July 1916; married 1942 Margaret Elaine Dovey (died 2012; one daughter, three sons); died Elizabeth Bay, New South Wales 21 October 2014.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies