Lord Weidenfeld: Remembering the refugee who lived to tell the stories of giants

The publisher, columnist and philianthropist recently launched fund to save Christians threatened by Isis - at the age of 96

Before he fled Vienna in 1938 as the Anschluss united Austria with Hitler’s Germany, George Weidenfeld duelled with a Nazi. The fight was drawn, although the Jewish student’s left-handed grip allowed him to outmanoeuvre his opponent.

After the Second World War ended, the refugee returned from London to Vienna while working for the BBC. He tracked down his fellow-duellist, gravely injured on the Russian front. The former foes shared a salami sandwich.

That sandwich, a bridge between seemingly irreconcilable people and worlds, might stand as a symbol of Weidenfeld’s approach to a life that saw him become perhaps the foremost figure in British publishing, until his death on 20 January aged 96.

It baffled some observers that a proud Jew and stalwart Zionist – who commissioned memoirs from Israeli premiers and even worked for the state’s first president, Chaim Weizmann – also published books by repentant Nazis: Hitler’s finance minister Hjalmar Schacht, and the architect Albert Speer.

Readers deserved, so the publisher insisted, to understand the motives and hear the voices of the history-makers – and in their own words, if possible.

In its peerless list of top-flight memoirs, diaries and biographies, his company opened doors to ministries, chancelleries and palaces. Lord Weidenfeld, the supreme big-game hunter of publishing, bagged books by the giants of his time, from Charles de Gaulle to Pope John Paul II.

In his perspective, power was always personal. Thanks to the diplomatic wizardry of the co-founder and the skill of expert editors such as the late Ion Trewin, the books of Weidenfeld & Nicolson made it accessible to all.

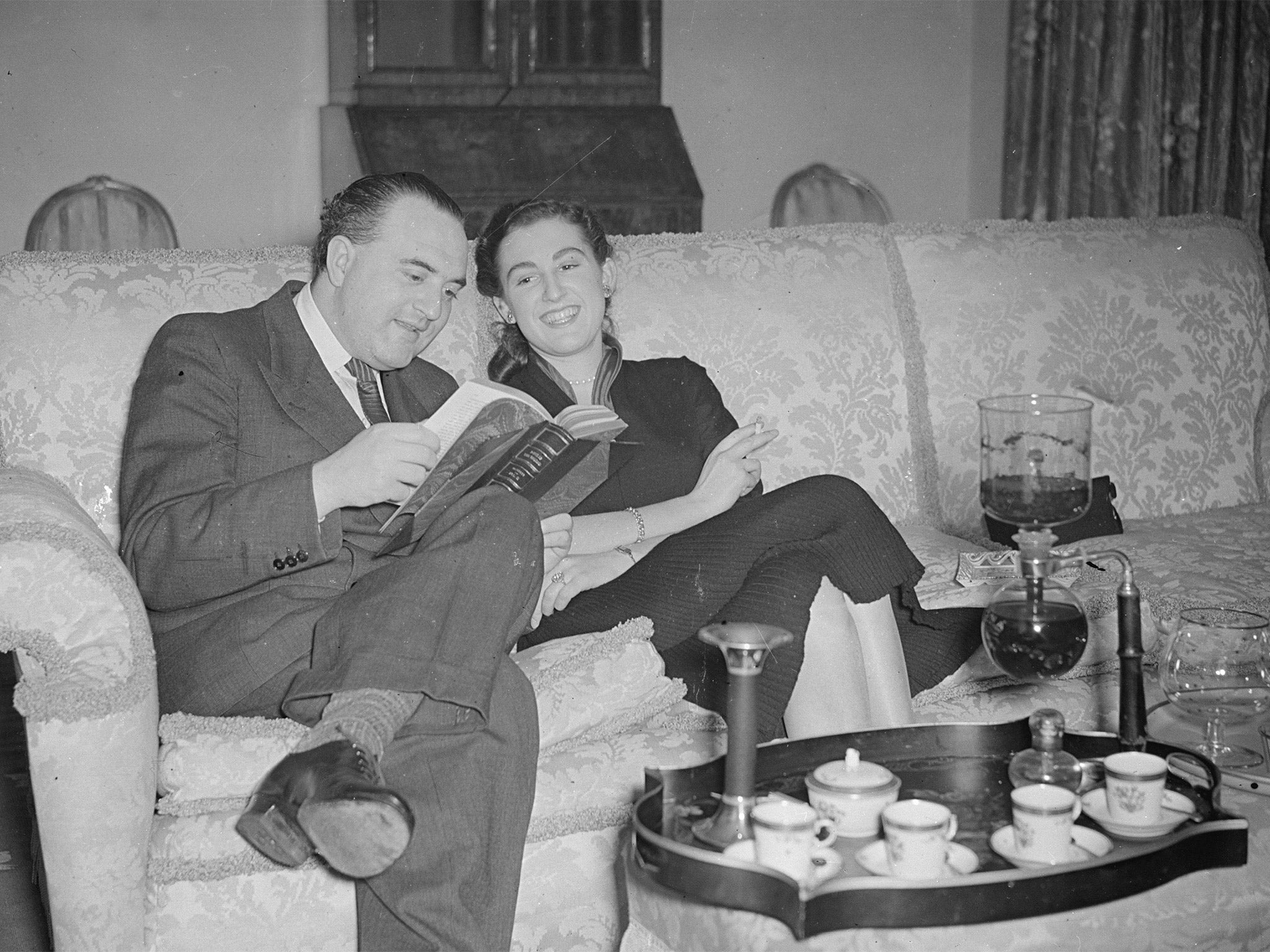

The much-married Weidenfeld used to complain that, in Britain, gossip-mongers showed an immature obsession with his romantic life. On the Continent, in contrast, he ranked as a serious philanthropist, patron and all-round intellectual go-between.

He had a point, especially as his humanitarian support continued right up to his creation in 2015 of the Safe Havens Fund to rescue Christians in Iraq and Syria from the deadly grip of Isis. Typically, he framed this generosity as the late repayment of a debt to the evangelical Christian family who had welcomed the 19-year-old refugee.

Individuals, and the relationships they might forge, mattered more than any abstraction. Only through them – statesman, scholars, thinkers, novelists – could ideas come to life.

Among his friends was Isaiah Berlin, who stands in relation to philosophy as Weidenfeld did to publishing. Human stories, in all their wayward complexity, give meaning to the principles and processes that govern our lives. And the axiom that Berlin borrowed from Immanuel Kant could serve as motto for the cross-grained, flawed but fascinating world of ambition and action revealed by Weidenfeld’s books and authors: “Out of the crooked timber of humanity, nothing straight was ever made”.

In the age of accountants and ideologists, he worked with the human grain.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments