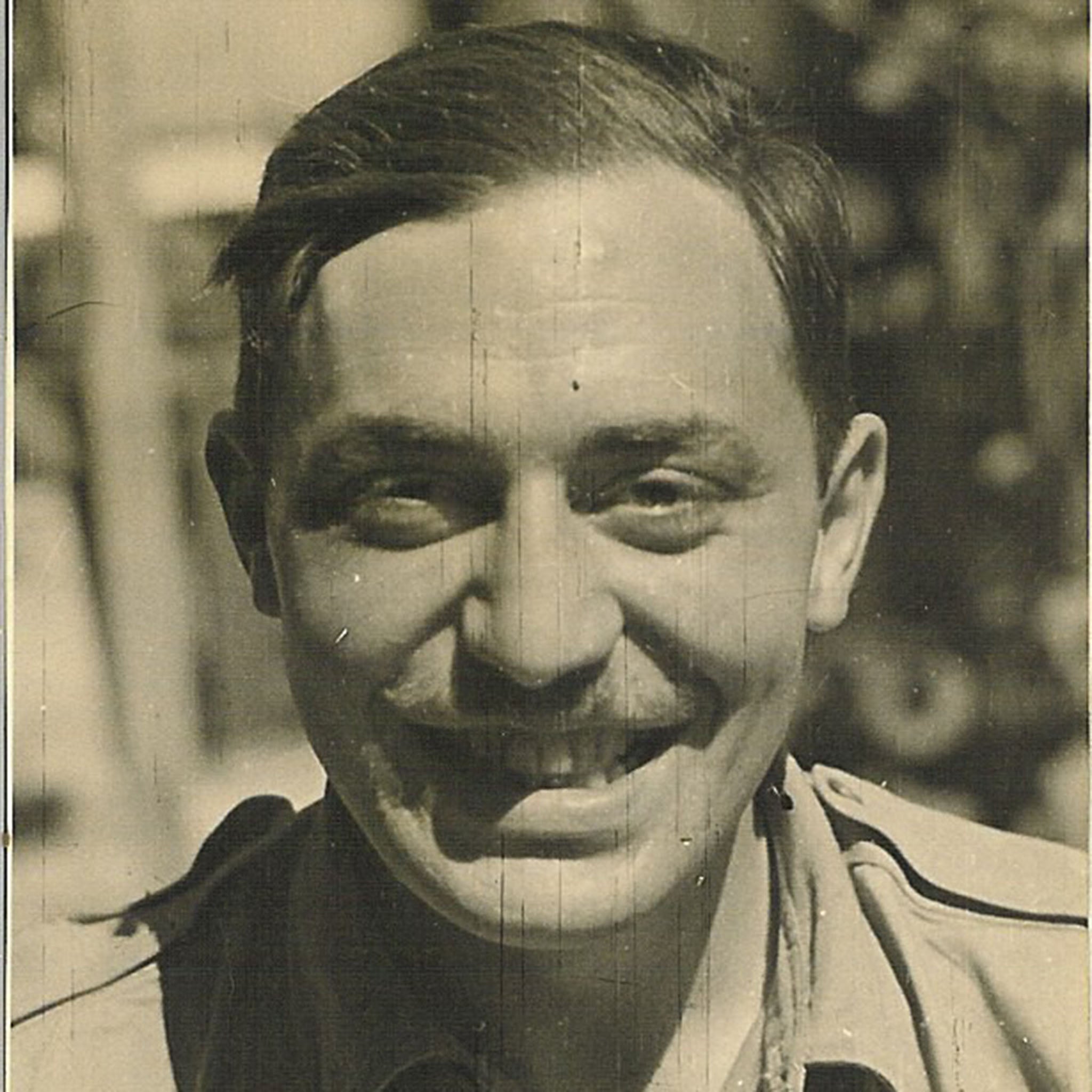

Major John Campbell: Special forces officer who was decorated for valour and played a crucial role in the campaign for Italy

'This feat of arms is one of the best examples of courage, leadership and self-control of an officer,' his MC citation read

Stealth and timing were the weapons “S” Patrol used again and again. It was the winter of 1944, in the marshes and forests south of Ravenna in Italy. In lonely farmhouses detachments of Germans, who had been told not to retreat before the advancing British Eighth Army, became prey to fear. At a homestead called “La Favorita”, for instance, after some unseen visitation not one man remained, yet half-eaten food still lay on the table, and there was no sign of a struggle.

Wild stories circulated and the frightened Hun forbore to replenish his positions with new troops. For the man who led these cloak-and-dagger raids, success was sweet. John Campbell, the “big awkward lad” whose orders the ranks had once scorned, was now hailed “the most daring of us all”.

With the surprise attack on and soon after 1 December, on the German-occupied customs post of Caserna dei Fiume Uniti, in which Campbell and his handful of men took 70 prisoners, the Germans had lost their last stronghold south of Ravenna. For his prowess, Campbell received an immediate Military Cross. “This feat of arms,” the recommendation says, “is one of the best examples of courage and leadership and self-control of an officer.”

It was also a feat of bluff, “S” Patrol having first done all they could to appear larger than they were. For some time they and the other few dozen men of PPA – “Popski’s Private Army” – had been steering their Jeeps fast along pine forest paths, firing their mortars and Browning machine guns, deliberately making multiple track-marks with their one self-propelled artillery gun for German aircraft to spot. This was because Allied forces on the Adriatic front line were sparse, troops having been transferred to France to join the D-Day invasion force.

Campbell, just turned 23, was a master of ruse, the silent approach, the attack so fast that not a shot was fired. In preparation for the customs-post triumph he led his men breast-deep in swamp water for six miles then lay up in a cowshed, observing the enemy’s routine, before pouncing. He also had luck: he once found his own large footprint less than an inch from a mine; and he survived the blowing-up of his jeep three times within 24 hours, an event that brought him the nickname “Bulldozer.”

In April 1945 he won his second MC, capturing 300 Germans with a force of 18 men, when “S” Patrol came upon a battery of four 88mm guns at Vigonovo firing upon British forces at Padua. Again Campbell led a rush, this time using Jeeps in line abreast, all guns blazing, against which the Germans were helpless.

Campbell had found his metier with the smallest of the Allied special forces, No 1 Demolition Squadron, more engagingly known as “Popski’s Private Army”. This was one of the more colourful elements of the scratch group of front-line units called “Porterforce”, headed by Lt Col Andrew Horsbrugh-Porter’s 27th Lancers. PPA, with about 80 members, was formed by a Belgian of Russian descent, Vladimir Peniakoff, re-christened Popski as Britons found his name hard to remember.

Peniakoff at first doubted Campbell, and forbade the La Favorita raid on 13 November, but then relented: “He pleaded so urgently,” Peniakoff recalled, “that I saw it would be hard on him and his men, and I let them go.”

Campbell’s plea sprang from a need to prove himself, made pressing by his experience during the second Battle of El Alamein in late 1942, when he found that his men, caught in cross-fire, had disobeyed his order and bolted.

He never could have lived with himself, he said later, had he shot the corporal who incited the flight. Nor could he bring himself to cast blame when explaining himself to his superiors. Thus, unjustly, did the label of coward stick, not to the corporal, but to Campbell, and would rankle for the rest of his life.

He had joined the 7th Battalion, Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders after being selected for officer training from the ranks of the East Kent Regiment. War drew him from studies in physics, chemistry and mathematics at St Andrews, and the expectation of a career with ICI.

The son of a society beauty, the Hon Eugenie Westenra, and her soldier husband, Major William Hastings Campbell, John was educated at Cheltenham College. After the war he was to prove himself again and again. When a fishing business he started in his native Ireland foundered when its only boat sank, he joined the Colonial Service. He was appointed MBE in 1957 for his work as a district officer and magistrate in Kenya, and in the same year was Mentioned in Dispatches for “distinguished service” as a territorial army officer there. What he did is not recorded, but he was known never to carry a gun. In Kenya he added to his French, German, Italian, and Serbo-Croat, as well as the Kikuyu, Dholuo, and Swahili languages.

He married Shirley Bouch, a secretary, in Nairobi Cathedral in 1959. Born Catholic, he became Anglican, and enjoyed the support of a helpmeet steeped in adventure: an oilman’s daughter, she had lived in Venezuela and fled the Japanese advance in Burma.

Returning to Britain in 1961, Campbell joined the Diplomatic Service, and the couple, having experienced African mud huts and a bungalow on Lake Victoria, lived for a time in a house boat at Twickenham. He was posted to New York, Belgrade, Bonn and Ottawa before becoming Consul General in Naples. The Queen, who visited in October 1980, appointed him CVO, and he and his wife distributed aid after the earthquake there the following month. On retirement he was made CBE.

Setting up home in Luston, near Leominster, Herefordshire, with three school-aged children, he established a business stripping road, farmyard, and runway surfaces, using a machine of his own design, and travelled to far-flung assignments in a motorised caravan. One sorrow was that his medals were stolen and have not been found. In his later years, as the last surviving PPA officer, he was chairman of the Friends of Popski’s Private Army, and wrote an appreciation of Popski for the 2002 edition of Peniakoff’s book, Popski’s Private Army, first published in 1950.

John Davies Campbell, special forces officer, businessman and diplomat: born Monasterevan, Co Kildare, Ireland 11 November 1921; MC 1944, and Bar 1945, MBE 1957, CVO 1980, CBE 1981; married 1959 Shirley Bouch (two daughters, one son); died Ludlow, Shropshire 30 July 2015.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies