How to be a recluse

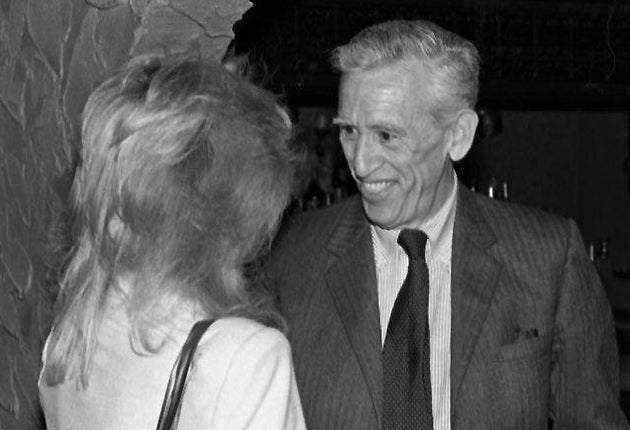

The late J D Salinger, Howard Hughes, Greta Garbo – all masters at hiding from the public. But it works only if the public wants to see you in the first place

Much as I admired the writing of J D Salinger the thought uppermost in my mind at any mention of his name was: how far was his reclusiveness a publicity stunt? Had Salinger, who died last Wednesday at the age of 91, calculated that his talent was ebbing, and so decided to cut his losses after that final published work appeared in 1965? It's surely possible that The Catcher in the Rye would not have sold 65 million copies if he had been knocking out a novel a year ever since. Catcher might have been buried by the subsequent output.

There would be a case for telling any author of a genuinely brilliant book "Hold it right there", and reclusiveness is a strategy always open to an author, whereas it is not an option for chat-show hosts, politicians or heads of corporations. (It's unfortunate, that... I mean, just think how much more charming Richard Branson would be if we never saw him or heard him.) The true appeal of reclusiveness in an author is paradoxical: it implies both modesty and arrogance, but especially the latter. Salinger broke all the rules that a young author is supposed to follow. First, he wouldn't do interviews, whereas I should say that the average first-time British novelist in 2010 is allowed to turn down one offer of an interview from Radio Stoke-on-Trent, and one request from some solicitous blogger to say where he gets his ideas from before his career is quietly terminated. Second, Salinger wouldn't give approval to the designs his publishers sent him for his books' covers. With normal authors, what happens is that the proposed cover is sent with a note to the effect, "We all love this, and we hope you do", the implied coda being "And if you don't, tough". But Salinger went so far as to insist that his books didn't have images on the cover, but only the title. After that, there was only one more commodity to withhold: words.

Withholding words is a high-risk strategy if you happen to be a writer, and in the case of Salinger, you do think he must have been at least partly mad. Then again, true reclusiveness always appears to shade into madness because, on the face of it, the practitioner is turning down money. This is the basis for all the mythology that develops. Did Salinger actually drink his own urine? How long exactly were Howard Hughes's fingernails? Was Greta Garbo really a promiscuous bisexual? And the madness – if it exists – risks undermining the reclusiveness because control is lost, as it very frequently is in the case of the desperate fame seekers at the other end of the celebrity hierarchy. As the failed actor Withnail (Richard E Grant) says in Withnail and I: "The only programme I'm likely to get on is the fucking news."

Short of hiding from the public for decades, the next most intriguing strategy is to be a writer or performer who "guards his privacy". This is the option favoured by most of the British elite. It is after all much harder to be a proper recluse in Britain, the available land mass being relatively small. When I think of the great American literary recluses, Salinger and Thomas Pynchon, I have a cinematic sensation of the huge scale of the country they inhabit. (My ignoble thought in the case of Pynchon, by the way, is this: is he copying Salinger, having noted Salinger's sales figures? If he is emulating the master, then he's very good at it – to the point where it has even been suggested that Pynchon is Salinger.)

If you're not going to stop writing entirely then you should at least be regularly turning down interviews, complaining when people say nice things about you, and imposing embargos on review copies of your books, as Martin Amis has done with his latest, The Pregnant Widow. This is not so much about withholding oneself from the public as about regulating the supply. As a young journalist, I once asked Martin Amis's publicity people whether I could interview him. "You can't interview him now," they carefully stated, "because he has nothing to promote. When he has something to promote, then you can interview him." It fascinated me that (a) he had licensed these third parties to say this on his behalf and (b) that he didn't immediately find something to promote (options would include his last book, or his next one, or just himself in general) purely for the sake of being in the papers. But no. There was a time to be famous, and a time not to be.

Julian Barnes was equally parsimonious with himself, and I knew a magazine editor who used to ring him up and try to commission him, always proffering double the usual rate of pay just to hear the silkiness of his, "I'm so sorry, but I'm rather tied up at the moment. So kind of you to ask..."

The success of the strategy of semi-reclusiveness is determined by the degree to which the number of offers of publicity refused at inconvenient times is exceeded by the numbers of opportunities accepted at convenient ones. One of our leading semi-recluses is Alan Bennett, who generally succeeds in being either everywhere or nowhere at any given moment. The one biography of him, written by Alex Games, is called Backing Into the Limelight, which seems about right, although Bennett has never said that he means to withhold all biographical details, rather that he will disclose them in a setting of his own choosing, by which he means for money, rather than by just incontinently yarning away on chat shows and panel games. (He stopped being on Quote... Unquote on Radio 4 because he found he was giving away all his best stories for a derisory fee.)

Of course you can't hide from people – to whatever degree – unless people want to see you (I mean, nobody would notice), and a brilliant work of art will not in itself make its creator famous. There must always be an element of PR, and the only ones able to refuse it or decry it are the ones for whom it has at some point truly worked.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies