James Lawton: The highs and lows of a tennis superstar

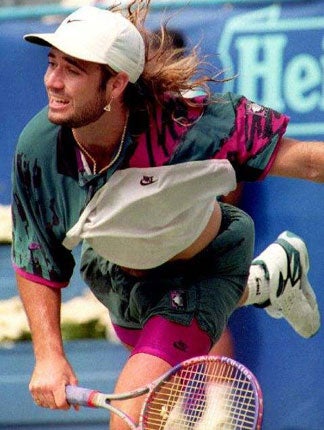

As Andre Agassi reveals the pressures of the game drove him to take the drug crystal meth, our writer recalls two astonishing encounters with the sporting legend

His former lover Barbra Streisand sent him flowers and called him her Zen Buddha, but that was when Andre Agassi was a young and apparently uncomplicated god of sport.

Now, at 39, he recalls the agonies that came with doing something he didn't like, the tyranny of his prototype bullying tennis father and a terrible moment of breakdown when he took the often lethally addictive drug crystal methamphetamine.

Millions of fans who loved the panache of the quirky Las Vegan, who won Wimbledon superbly as a 22-year-old and declared that henceforth he would consider the Centre Court his first home, will be further shocked by the revelation in his autobiography that he lied to the tennis authorities when he failed a drugs test in 1997. He produced the classic explanation: his drink had been spiked.

The truth was that the pressures of his life had become impossible to manage. It is also true that when you re-visit the young Agassi who seemed to have the world at his feet, there is some evidence that he was in the early stages of a crisis that has afflicted so many of the greatest achievers in sport down the years, not least in the superficially glamorous world of tennis.

My first encounters with the star came in Florida and Germany in the spring and early summer of 1993, when injury was threatening his defence of the Wimbledon crown he had won so brilliantly the previous year when he repelled the awesome serve of Goran Ivanisevic.

In Florida, he agreed to a lengthy interview, but bizarrely only if I agreed to drive his golf buggy while he played a round that he had been aching for during long sessions of work and rehabilitation in Nick Bollettieri's tennis camp – an early clue, perhaps, that the boundaries of the game in which he had achieved so much fame were already pressing in.

It was one of the more astonishing golf rounds anyone is ever likely to witness. He played it at lightning pace, at one point complaining, albeit with some charm, that my driving was not as perfect or as quick as he would like. He leapt from the buggy and played shots which he had barely addressed. They were astonishing shots, beautifully flighted and controlled to the point where his par was never endangered. He finished with a birdie, his face lighting up when the ball went in. In between shots, he released a stream of consciousness that was relentlessly and perhaps, on reflection, suspiciously upbeat.

He talked of his close relationship with John McEnroe, and of how he had spent hours on the telephone drawing out the secrets of a great competitor. He spoke of his special relationship with the great diva Streisand, one that went so much deeper than passing romance. Most obsessively he talked of the "high" that came with winning Wimbledon. Yes, the high.

He packed the private plane that flew him home to Vegas with newspapers containing accounts of his defeat of Ivanisevic. "I read them all and then re-read them all over again repeatedly, because I wanted to confirm in my mind what had happened. It went on for weeks after I got home. I would be with friends, talking about all kinds of things but my mind was still stuck on what happened at Wimbledon, what it meant to me and how it might affect the rest of my life."

We know better now that what it meant was the building up of demands which ultimately became impossible to meet, at least without some chemical assistance. In his autobiography he is candid about the weight of his father's presence and the rage he knew would follow if ever he whispered his hatred of the game which dominated his life.

Agassi goes all the way back to the age of seven and his desire to just walk off court and have a sense of heaven, free from the promptings of his father. "But I couldn't," he reports now, "because if I did my father Mike (a former wrestler) would have chased me around the house with a racquet."

Tennis is of course littered with such stories of unbridled demands on children, and perhaps the only surprise in the Agassi case is that he avoided any suspicions about his own traumas for so long. Equally accessible is the evidence of the havoc wrought in sportsmen and women not only by performance-enhancing drugs but also by those of "recreation", which have so frequently been employed by "stressed" superstars.

The authors of a new book on pressures in sport, Winning At All Costs: Sporting Gods and their Demons, devote a whole chapter to "The Svengali Syndrome – Fathers Stalking the Tennis Courts". Their chief challenge must have been where to start.

The victims are, after all, known well enough. Jennifer Capriati was rushed into professional tennis at the age of 13 and, soon enough, was arrested in a motel after a drugs episode. She fought her way back with some distinction, an epic performance when you consider her father had gone on record with his strategy. It was to get his daughter into the professional game early enough to win some big money before the onset of "burn-out". He also joked that he had had Jennifer performing push-ups in her cot.

At one of Capriati's first tournaments, Martina Navratilova said: "I would never have a daughter of my own out there in the professional game at that age." She also expressed reservations about the pressure on her namesake, Martina Hingis, whose career was interrupted by charges that she had resorted to cocaine.

Andrea Jaeger retired to a nunnery after precocious progress in professional tennis and allegations that her father had introduced her to the game at the age of eight – and reinforced his ambitions for her with his belt. So it goes, case after case. Now Agassi tells us that all those lost and bewildered little girls had companions on the other side of the gender net.

I saw Agassi a little later in that summer of 1993. He was competing at the Halle championships in Germany, one of the main sources of preparation for Wimbledon, along with the Queen's Club in west London, but still under the cloud of injury. He practised indoors when the rain came – and then hurried to his hotel room, his face strained and his mood much less buoyant than when shooting his quick-fire round on the Florida golf course.

He said: "It's hard to describe the feelings I've had on the way to Wimbledon, especially back in April when I had to pull out of tennis for a while. It's just unbelievable how down you get when you fear that something has gone wrong with your body.

"That's what it comes down to in the end. You take certain things for granted and then, so soon after I won Wimbledon and believed I had made this great breakthrough, I was going through these various levels of concern and then something very close to despair. One minute you are the king of the world and then you are wondering if you are going to survive.

"You have all these business commitments, this life mapped out ahead of you, all built on the premise that you are going to carry on being a tennis star. And then you wake up one day and have some really serious problems and wonder if it is all over, and everything has gone. Will you ever be able to play in the old way again?"

In view of his revelations this week, it is maybe reasonable to speculate that there was something else at the heart of his questioning. He must have wondered, once he had arrived back in that most diverting of cities, Las Vegas, if he would ever again get the rush that came when he won Wimbledon – the exhilaration that came when he beat the world.

If that was the case, he was undoubtedly not the first or the last to ask the question. When the Bath rugby player Matt Stevens recently confessed to cocaine use and the collapse of a brilliantly unfolding career, he talked of both a void and an illness. Diego Maradona would have understood this only too well. After his astonishing displays in the Mexican World Cup of 1986, Maradona returned to club football in Naples and for a while continued to perform phenomenally, winning the scudetto league title and bringing such joy to its citizens that they flew the club colours up to the peak of Vesuvius. But by then there were other fires burning in the life of the great star, and soon enough he was one of the Camorra's best cocaine customers.

So much more than Andre Agassi, Maradona is a living, tortured example that some glories come at a potentially devastating price.

In the case of Agassi, though, perhaps those who feel betrayed by his confessions might better reflect on the fact that he does appear to have survived some the worst of the pain that came to him at such an early age.

After his meths and his lies, two years later he won two more Grand Slam titles, the French and the US Opens, and after winning in Paris he danced the victory waltz with the women's champion, Steffi Graf. When they married soon after, they were hailed as tennis's perfect couple.

It is an image they have maintained impeccably until this week of revelation and even now it is, surely, not so hard to understand, at least a little, the severity of the wounds that have so long been hidden by their A-list smiles.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies