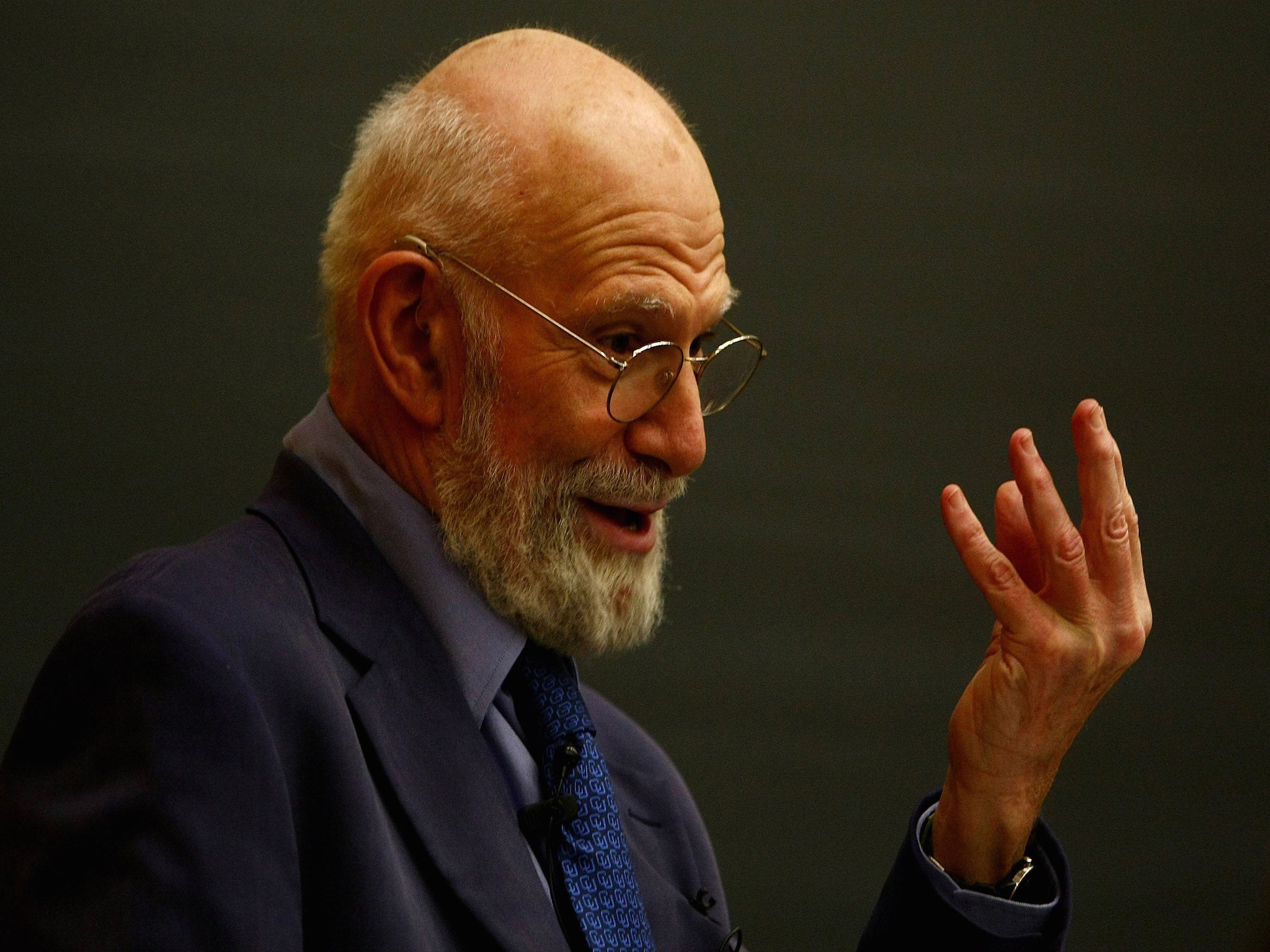

Oliver Sacks dead: Neurologist and acclaimed writer dies aged 82

His personal assistant, Kate Edgar, confirmed the cause was cancer

Oliver Sacks, the British-born neurologist and acclaimed writer once described as the “poet laureate of medicine”, has died at the age of 82.

The polymath doctor, who was the author of The Man Who Mistook His Wife For a Hat, announced in February that his “luck had run out” and he had terminal cancer. He added that he intended to spend his remaining months living “in the richest, deepest, most productive way I can”.

Dr Sacks’ long-time personal assistant confirmed that he had died on Saturday at his home in New York, where he had lived since 1965 after being born in London to his surgeon father and GP mother.

Among those who paid tribute to Dr Sacks, renowned for his ability to straddle academic and artistic disciplines while often combining both in his writing, were the author JK Rowling, who described him as “great, humane and inspirational”. Fellow academic Richard Dawkins said he had “greatly admired” him.

Born in 1933 and educated at Oxford University after being a wartime evacuee and a victim of boarding school bullying, Dr Sacks was best known for his books chronicling some of the medical conditions he encountered in six decades of investigating the workings of the human mind.

His 1985 collection of essays based on his clinical notes, The Man Who Mistook His Wife For a Hat, was an insight neurological conditions and the remarkable mental powers of those with disabilities such as autism or Tourette’s syndrome. The book became the basis for an opera but it was Awakenings, his account of how he treated catatonic patients in the late 1960s with a drug to bring them out of their frozen state, that brought his work to a mass audience. Dr Sacks recognised the patients, based in a ward in a psychiatric hospital in the Bronx, as victims of sleeping sickness, the pandemic which swept the world between 1916 and 1927. His treatment with the then experimental drug, L-DOPA, enabled many to enjoy “enduring awakening”.

The 1990 film version of Awakenings, which starred Robert De Niro and Robin Williams, was nominated for three Oscars.

Jacqui Graham, Dr Sacks’ publicist, said he had been “unique” and always “completely full of love for life”. She told BBC News: “He died surrounded by the things he loved and the people he loved, very peacefully… He taught us a great deal, right up until the very end. He always taught us what it was to be human, and he taught us what it is to die.”

The author of more than 1,000 journal articles as well as countless letters and clinical notes, Dr Sacks was garlanded with honours, including being made a CBE by the Queen. He was professor of neurology and psychiatry at New York’s Columbia University and professor of neurology at NYU School of Medicine.

But it is for his ability to enliven the dry stuff of a clinician’s observations with an empathy-laden retelling of his patients’ lives that he will be most remembered.

His website notes that The New York Times referred to him as “the poet laureate of medicine”, while the 1973 cover of the first edition of Awakenings, quoted the eminent British literary scholar Frank Kermode saying: “This doctor’s report is written in a prose of such beauty that you might well look in vain for its equal among living practitioners of belles lettres.”

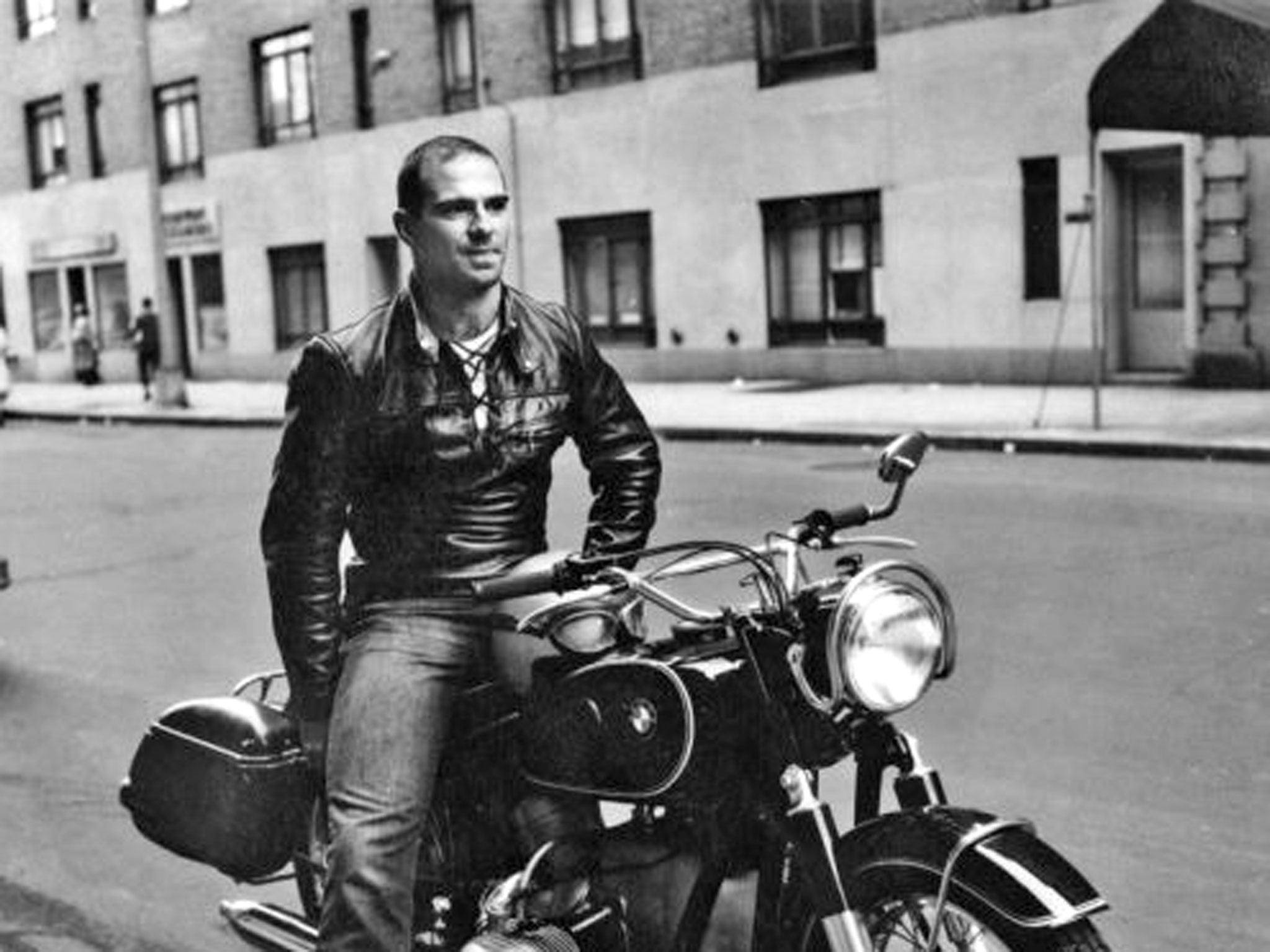

For his part, Dr Sacks, who counted among his fascinations a passion for motorbikes, was unstinting in his celebration of the infinite variation of human beings and his “gratitude” for life. He recently wrote: “I cannot pretend I am without fear. But my predominant feeling is one of gratitude. I have loved and been loved; I have been given much and I have given something in return; I have read and travelled and thought and written… Above all, I have been a sentient being, a thinking animal, on this beautiful planet, and that in itself has been an enormous privilege and adventure.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments