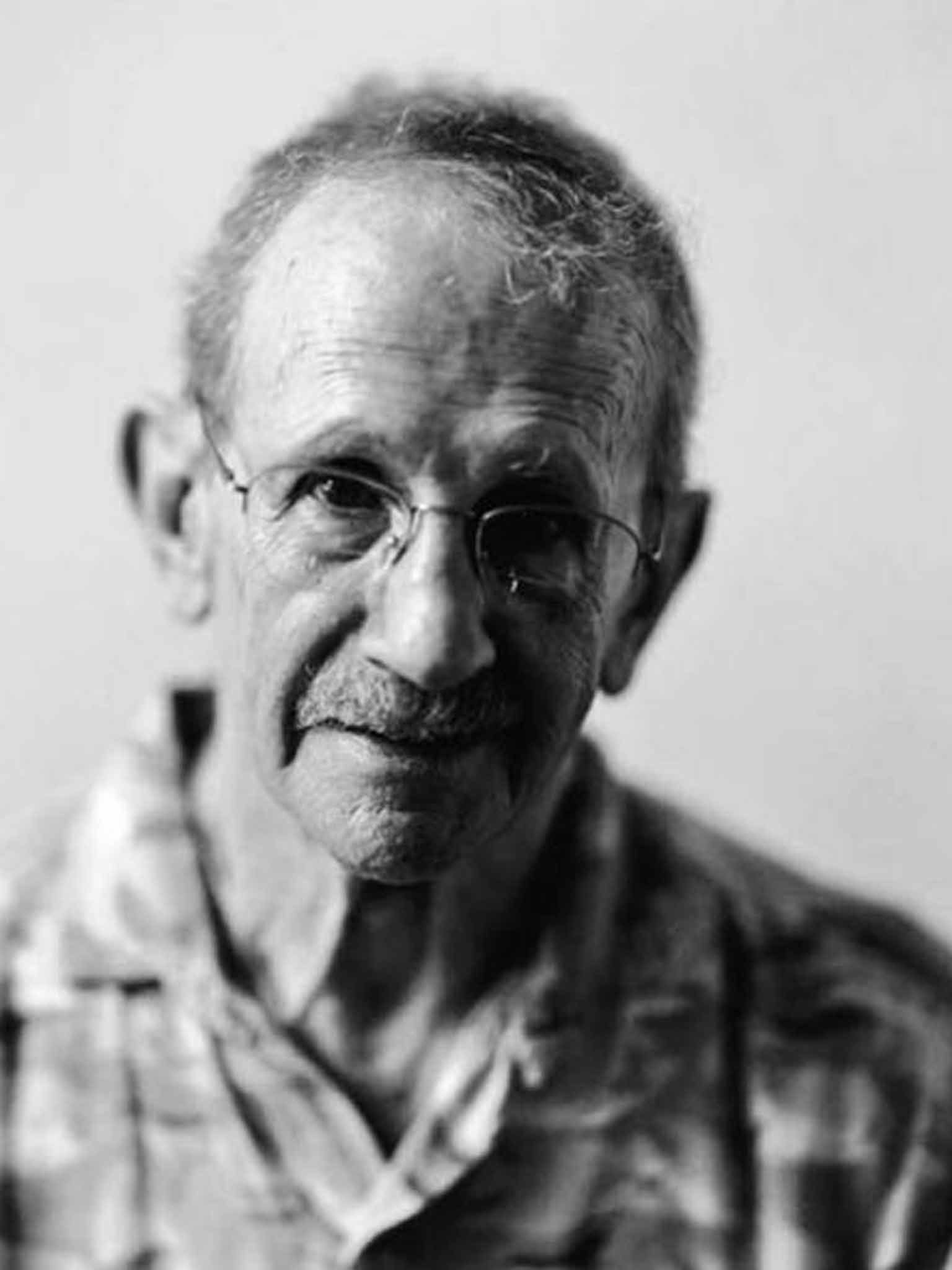

Philip Levine: US poet laureate who explored with rage and sadness the working lives of the American people

He worked in laconic free verse that evolved into a more natural, rhythmic style

First anger, then irony, then tenderness, and then finally love: those were the successive growths of Philip Levine's poetic emotion – and in the evolution of his one great subject, which was the lives of American working men and women. In a sense, all of these feelings, with the exception of irony, which is a learned literary technique, were in place from the beginning and remained so until the end. Even in his last years, Levine could still express rage at what had happened to his once-vital native city and its people.

He was born in Detroit, Michigan, in January 1928, 18 months before the Wall Street Crash stalled America's apparently unstoppable rise and plunged the West into Depression. His parents were Russian-Jewish immigrants, but apparently told the boy – perhaps swayed by the infamous Detroit radio priest Fr Coughlin, who naturalised Nazi ideas in his anti-semitic "Social Justice" crusade – that he was of Iberian extraction. This led the young Levine to a passionate interest in Hispanic literature: Antonio Machado and Federico Garcia Lorca were strong influences, and Levine later translated works by Gloria Fuertes and Jaime Sabinas.

Conscious of his outsider status, Levine went through the Detroit public school system, graduating in 1946, before attending Michigan's only public-research university, Wayne State, graduating in 1950. By then, though, Levine had already been working night-shift jobs for nearly a decade. He took up permanent employment at Chevrolet Gear and Axle and at Cadillac, writing poetry in the daylight hours, encouraged by his mother, Esther Prisckulnick (Priscol) Levine, who sold books. In 1999 Levine dedicated The Mercy to her memory.

He met his two greatest American influences when he attended, as a non-matriculating student, the famous Iowa Writers' Workshop, where Robert Lowell and the more saturnine John Berryman were both visiting teachers. Soon he was teaching writing and studying for a degree at Iowa Technical University, where he gained an MFA in 1957. Immediately after, he set off for the West Coast with his second wife, Frances Artley; a previous marriage to Patty Kanterman had ended after two years. In California, he was hosted by the poet and critic Yvor Winters, who supported him – but Levine had already won a Jones Fellowship at Stanford University and was becoming recognised as a rising voice in American poetry.

He had nothing about him of the mannered proletarianism of the 1930s New Masses writers, preferring to work in laconic free verse that evolved into a more natural, rhythmic style. He spoke feelingly and articulately about his own poetic development, later publishing two books of prose, Don't Ask (1981) and So Ask (2002), and a volume of autobiography, The Bread of Time (1994). Around that time, he told a British journalist: "I had to learn to temper the rage I felt against the people who had crushed me and rejected me with something tender for those who had taken me in and blessed me, allowed me to live." He spoke of writing for and about a constituency whose "presence seemed utterly lacking in the poetry I inherited at age 20."

Levine's belief in the transformative power of poetry is evident from his very first collections, On the Edge (1963) and Not This Pig (1968), but is most clearly dramatised in the span of Ashes: Poems New and Old, which won him the National Book Award in 1980 and the National Book Critics Circle Award the year before.

The early snap and snarl gave way to something more thoughtful. In his later years he often cited the example of Thomas Hardy, who wrote verse doggedly in his declining years, always in different poetic forms, every verse tailored to the subject. Levine was no more an establishment figure, but neither man went without some establishment recognitions. Levine taught for many years at Cal State in Fresno, dividing his family time between there and New York, where he was a distinguished poet in residence in the creative writing programme at New York University.

He chaired the literature panel of the National Endowment for the Arts and from 2000 served as chancellor of the Academy of American Poets. In 2011 he was elected America's 18th poet laureate, in succession to WS Merwin. Two years later, his lifetime achievement was recognised by the Wallace Stevens Award.

Levine believed that if he could transform his "stupid" experience into poetry, he could invest it – and the experience of other working people – with the dignity and value it did not visibly possess on its own. He also believed that poetry was a route to understanding, and "if I could understand my life, or at least the part my work played in it, I could embrace it with some degree of joy – an element conspicuously missing from my life."

Those close to him might have disagreed with the latter part, but the shadow of industrial decline, exploitation of labour, anti-semitism, cultural confusions and uncertain origins never quite left the man. He died of pancreatic cancer on the day dedicated to love rather than anger.

Philip Levine, poet: born Detroit, Michigan 10 January 1928; married 1951 Patty Kanterman (divorced 1953), 1954 Frances Artley (three sons); died Fresno, California 14 February 2015.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies