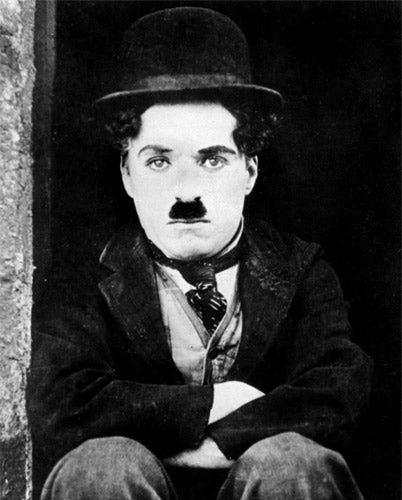

The Big Question: Does Charlie Chaplin merit a museum in his honour, and what is his legacy?

Why are we asking this now?

A $50m project is under way to open a museum on the shore of Lake Geneva in 2011, dedicated to the memory of Charlie Chaplin. It will screen his great films, such as City Lights, The Kid and The Great Dictator, tell the story of his long career, show multi-media exhibits and dramatise the process of film-making in the early 20th century.

Why on earth is it in Geneva?

The house that will be turned into the museum is Chaplin's retirement home in Corsier-sur-Vevey, where he spent the last 20 years of his life. He couldn't live in the USA because he was accused of "un-American activities" during the McCarthy period, and barred from his adopted home in 1952. He returned to American just once thereafter, to receive an honorary Oscar in 1972 (and a five-minute ovation.)

Would any other city be a suitable location for a shrine to the great man?

How about London? He was born in East Street, Walworth, south London, home of the celebrated street market, in 1889. His parents were both music-hall entertainers but, because his father was alcoholic and his mother had bouts of insanity, Charles and his brother scratched out a pauper's existence in the streets of Lambeth, setting the template for the pathos and deprivation of his classic films.

Pathos and deprivation. That's the trouble, isn't it? We prefer Buster Keaton, don't we?

Chaplin certainly dealt in sentimental subjects, far more readily than the stoic and stony-faced Buster. But the Little Tramp persona is a great deal more than a lovelorn down-and-out. He's a master of enterprise, gallantry and what we now call street wisdom. He exists outside bourgeois comfort and conventional morality, the better to laugh at both. "You know this fellow is many-sided," he wrote, "a tramp, a gentleman, a poet, a dreamer, a lonely fellow, always hopeful of romance and adventure. He would have you believe he is a scientist, a musician, a duke, a polo player. However he is not above picking up cigarette butts or robbing a baby of its candy."

So the Tramp is basically Chaplin himself?

No, he's a more adventurous version of the nervous, rather helpless 21-year-old immigrant who came to New York in 1910. According to Lucy Moore's biography of the 1920s, Anything Goes, Chaplin found New York "a frightening and unfriendly place", where he felt "lone and isolated". His sense of poverty penetrated deeply. When he finally earned a good pay packet, three years later, he booked into a fancy hotel for the first time and sat by the bath turning the hot and cold taps on and off, thinking, "How bountiful and reassuring is luxury."

So one might start a fan club – but a museum?

It will be a fitting tribute to his role as a film-maker. Bernard Shaw called him "the only genius to come out of the movie industry", precisely because he did so much: as actor, director, producer, scriptwriter, even composer of soundtracks. He's the vital link between the late-Victorian music hall and the classic era of Hollywood film-making. He made it his personal project to cheer up American audiences during the Depression years, and to warn them of the rise of totalitarianism. He was the master of the silent movie (even after the advent of the Talkies) that could be understood and appreciated globally, especially by the new waves of immigrants who arrived in America as penniless underdogs – just as he had done in 1910. The museum will feature the paraphernalia of film-making that realised this dream: the film sets, the Expressionist machinery from Modern Times, even the piano on which he composed film scores.

How influential was he as a director?

Chaplin was a demanding director, a perfectionist just as driven as Stanley Kubrick (like him, he could demand as many as a hundred takes for a single scene) and an improviser as inventive as Mike Leigh, working from a ghost of a script and seeing how bits of dramatic "business" turned out on film.

Did his contemporaries think highly of him?

Absolutely. The critic James Agee called his performance in City Lights, "the greatest single piece of acting ever committed to celluloid." Harpers magazine compared him to Aristophanes, Cervantes and Swift. New Republic magazine went on about the "democratic breadth" of his appeal. Edmund Wilson, America's greatest critic, called his reactions "as fresh, as authentically personal, as those of a poet." The British belletrist Beverly Nichols wrote, "There is no tragedy of life's seamy side which Charlie Chaplin does not know, not only because he has a great heart but because he has shared the tragedy himself."

So why did everyone go off him?

They weren't terribly impressed when it was revealed that he'd impregnated the 16-year-old actress Lita Grey, demanded that she had an abortion and, when she refused, married her in secret and proceeded to neglect and abuse her for two years. Further details that he had demanded oral sex (considered an outrageous perversion at the time) and invited other women to share the marriage bed further tarnished his career.

The divorce cost him $1m in legal fees and groups formed across middle America calling for his films to be banned. His virtual obsession with young girls, whom he "mentored" and later bedded, led him into court scandals and paternity suits. Politically he was always left-wing, and was criticised for supporting Russian Communism - in, for instance, supporting the opening of a second front in Europe in 1942 to help out the Red Army. His later film, Monsieur Verdoux, bitingly critical of capitalism, led to protests in American cities.

But everyone loved him in the UK, right?

Actually, no. He was criticised in the British papers for failing to join the army to fight in the First World War. In fact he had offered his services but was turned down for being too small and weedy. But the accusation stuck, and – though recommended for a gong in 1931 – he wasn't knighted until 1975, two years before his death.

And that's why there's no museum to him here or in the US?

Indeed. Although he has a star in the Hollywood Walk of Fame. And a statue in London's Leicester Square.

And is his legacy secure?

Safe as houses. Despite his occasional bursts of tyranny and rambunctiousness, his chronic satyriasis and taste for young girls, he remains a giant of film history, a one-man industry, a vast, exuberant creative generator, and a perfectionist who insisted on the highest quality of product, even when the industry was in its infancy. His influence on modernist writers (such as Samuel Beckett) as well as film-makers, his blending of comedy, slapstick, pathos, surrealism and visual trickery affected the entire industry. It's time someone turned his private mansion into a public shrine.

Is Chaplin still worthy of his status as a 20th-century icon?

Yes...

* He gave the world a handful of masterpieces with sequences that are part of movie legend

* He profoundly influenced the history of comedy, bringing to it new depths of feeling and emotion

* He transformed the process of composition, framing, cutting, wiping, even music and choreography

No...

* He belongs to a forgotten era of jerky camera shots and gurning faces, with no relevance to modern film

* He deals in the winsome, the mawkish, and the pathetic, and is about as interesting as Norman Wisdom

* He was a a pederast and a fellow-travelling pinko, not to be held up as an example of human endeavour

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies