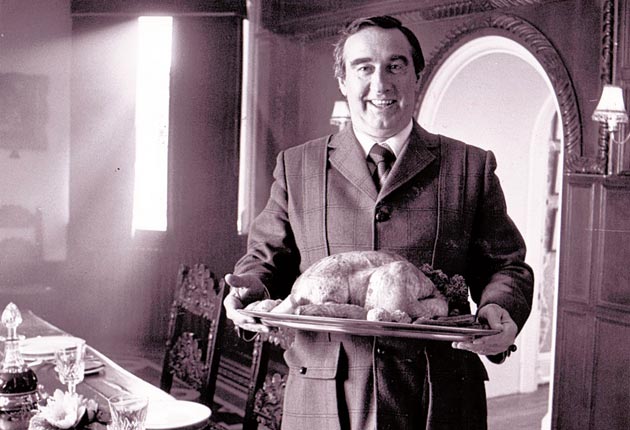

The man who taught Britain to talk turkey

Loved by many but by no means all, Bernard Matthews has died. Cahal Milmo marks the end of a 'bootiful', and controversial, life

As the man most inextricably associated with Meleagris gallopavo and the 70 products he fashioned from its intensively farmed flesh, Bernard Matthews would probably have flashed his trademark grin upon learning he had died on Turkey Day.

The multi-millionaire doyen of the poultry industry who thanks to his tweed-clad avuncular appearances in his company's television adverts became one of Britain's most widely recognised brands, died at his Norfolk home on Thursday – Thanksgiving or Turkey Day in the United States – after a lifetime dedicated to turning a once-a-year luxury into a cheap quotidian protein produced on an industrial scale.

The 80-year-old entrepreneur stepped down from day-to-day involvement in his eponymous food empire in January. But under his tutelage, Bernard Matthews Farms Ltd had grown from a (literally) backroom operation in the ramshackle mansion he bought with his wife in 1953, to become Europe's largest turkey producer, churning out nearly 8m birds a year and with a turnover of £330m.

The mechanic's son whose Norfolk burr was such a powerful marketing tool became a pioneer of intensive farming techniques that fed millions of people, and made him an estimated £300m personal fortune. They also earned him opprobrium as the purveyor of moulded, sliced and breaded poultry shapes, and allegations that birds on his farms suffered cruelty.

Noel Bartram, the company's chief executive, who knew the meat magnate for more than 30 years, said yesterday: "Rarely has any business been as synonymous with the hard work and values of one man. He is the man who effectively put turkey on the plates of everyday working families."

The tycoon put his entry into the poultry business down to good luck. He turned up at a market in 1950 and found a parrafin oil incubator for sale on the same day as 20 turkey eggs. Without the incubator, his eggs would have been good only for omelettes. Instead, 12 of the eggs hatched and he turned his investment of £2.50 into a £9 profit. He said later, "I thought, this is all right."

At the age of 25, Matthews, and his wife Joyce, bought a dilapidated Elizabethan pile, Great Witchingham Hall. The couple occupied two rooms, cooking on an upturned electric fire, while rearing turkeys in the other 34 rooms.

He rapidly scaled up production (he was one of the first to use artificial insemination for poultry), and expanding by buying up disused American airbases while selling chicks and expertise to the Communist bloc.

His breakthrough came in the late Seventies ,when he began to sell his pre-packed Turkey Breast Roast. In the TV ads that he was persuaded to front he wore his woollen country jacket and plus fours, and pronounced the catchphrase "They're bootiful, really bootiful." The British public bought into the image of the genial gentleman farmer in a way even Matthews could not have anticipated. Within eight days of the launch of the ads the company had sold £2m of the turkey roasts.

Matthews, who had left school at 16, recalled: "That was the real change in the company. Until that point, I didn't realise that you could really sell turkey in huge volumes."

However the flip-side of commercial success was growing concerns about the welfare of birds that Matthews boasted once would have cost a week's wages and now could be bought for just two hours' pay. Then in 2005, the company was targeted by chef Jamie Oliver for producing Turkey Twizzlers, the chief villain of his crusade to improve school dinners, and there also followed a scandal over footage of two contract workers playing baseball with live birds at a Bernard Matthews farm in Suffolk.

The firm took out full-page adverts in national newspapers denying there had been abuse at the plant, only to then fall foul of an outbreak of bird flu in 2007.

Priding himself on producing the "perfect protein", Matthews himself was a tough old bird, and Britain's appetite for his wares is largely undimmed. After staff cutbacks in the recession in 2009, Bernard Matthews Farms this year said its retail sales were up 4 per cent.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies