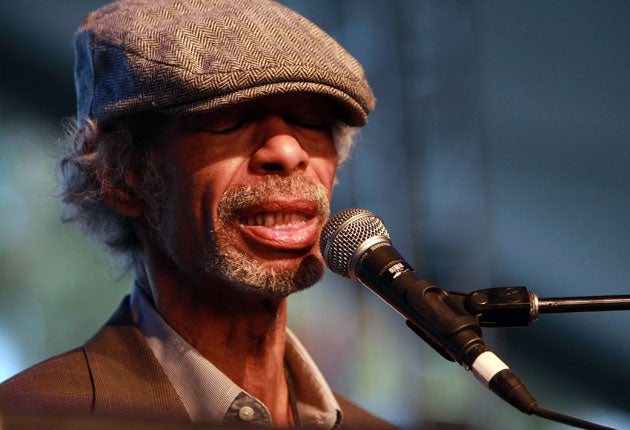

The voice of black America falls silent

Gil Scott-Heron, who has died aged 62, fired today's rappers with his biting satires

"Eccentric, obnoxious, arrogant and selfish". That's how Gil Scott-Heron described himself on his final album, I'm New Here, released last year. He also confessed on it to having an "ego the size of Texas", adding, with a gallows-humour chuckle: "If you've gotta pay for all the bad things you've done... I've got a big bill coming." A touching piece of self-deprecation from the sexagenarian jazz poet, but if one factors in all the good he achieved over the course of his life, Scott-Heron's balance sheet is unquestionably deep into the black.

In pop, you don't need to be the first. Only the best. Scott-Heron's style wasn't wholly original: others had experimented with spoken narratives over jazz backing; and Nina Simone had already perfected a mood of understated, measured anger. Nor was he the first to deliver politicised Black Power diatribes in musical form. But nobody brought these strands together better than Scott-Heron, which is why he can truly lay claim to being the god-father of hip hop.

Gil Scott-Heron was born in Chicago on April Fool's Day 1949. His absentee father, Gilbert, was a Jamaican footballer and the first black man to play for Celtic FC. His mother, a librarian, struggled to raise him alone, so Gil was taken to Tennessee to live with grandmother Lily Scott, to whom he later paid tribute on "On Coming from a Broken Home (Part 1)". When Lily died, Gil, aged 13, rejoined his mother and grew up in the Bronx, later moving to the multi-racial melting pot of Manhattan's Lower West Side. At school, his prodigious essay-writing talents impressed an English teacher so much that he was recommended, and gained admittance, to the prestigious Ivy League prep school Fieldston, which had previously educated Arbus, Oppenheimer and Sondheim.

He then attended Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, the first black university in America, which had a strong tradition of jazz and poetry. There he made his first forays into music, playing piano in a rock'n'roll band. There, too, he came into contact with the ideas of Malcolm X and Huey Newton, which would quickly find expression in his art.

A published author by the age of 21 (he'd already written a novel called The Vulture), it was inevitable that Scott-Heron's finely tuned, literary lyrics would work as well on the written page as they did on record. But to merely read his words is to miss out on an exquisitely laconic, cooler-than-cool, Bourbon-soaked delivery.

The opening track of his 1970 debut album, A New Black Poet – Small Talk at 125th and Lenox, was extraordinary. Coming after a succession of inner-city race riots, "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised" was an incendiary wake-up call to black America to switch off the TV set and do something less passive instead.

Its style, polemical and impassioned but bitterly funny, would be repeated throughout his career, on signature tracks like "Whitey on the Moon", a witheringly witty satire contrasting the extravagance of the space programme with the appalling state of healthcare provision in the cities: "A rat done bit my sister Nell (with Whitey on the moon)/Her face and arms began to swell (and Whitey's on the moon)/I can't pay no doctor bill (but Whitey's on the moon)/Ten years from now I'll be payin' still (while Whitey's on the moon)".

Scott-Heron was nobody's idea of a saint. "The Subject Was Faggots" is a nasty, mean-spirited description of a gay ball (in which he recalls, with distaste, seeing "Misses and miseries and miscellaneous misfits" who are "giggling and grinning and prancing and shit"), while "Enough" imagines the rape of white women as a form of reparation for slavery.

Yet he always had an acute eye for the social problems of the day. "Home Is Where the Hatred Is" was a bleak tale of heroin addiction, while his classic single "The Bottle" lifted the lid on inner-city alcoholism.

Scott-Heron's late Seventies recordings with musician Brian Jackson became a rich seam of source material for the acid jazz movement. But by this time Gil himself was a victim of substance addiction and would serve time in prison for cocaine possession. During the wilderness years of the Eighties and Nineties, he released just one album (Spirits, in 1994).

He was going through a burst of renewed creativity when he fell ill after a visit to Europe this year. The day before he died, the American state of Vermont became the first to offer single-payer universal healthcare. He lived long enough to see a US administration, led by a black president, finally taking its first steps in prioritising the health of its citizens... and Whitey's no longer on the moon. Gil Scott-Heron's work here is done.

Under the influence: Five acts who sipped from Scott-Heron's bottle

Melle Mel

The gritty urban realism of Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five's "The Message", written by rapper Melle Mel, or the anti-cocaine anthem "White Lines", would have been even more startling had Gil Scott-Heron not already done it all a decade earlier.

Ice-T

Sire president Seymour Stein called Tracy Morrow a black Bob Dylan: an epithet frequently applied to Scott-Heron himself. The former hoodlum's LA gangland narratives merely took Gil's blueprints and transplanted the location to the West Coast.

Chuck D

On hearing of Gil's death, the Public Enemy firebrand Tweeted "RIP GSH... and we do what we do and how we do because of you", confirming the suspicion that Chuck must have been a massive fan of his radicalised rap forerunner. No GSH, no PE.

Kanye West

A late-life love-in developed between Scott-Heron and West, the latter sampling "Home Is Where the Hatred Is" and "We Almost Lost Detroit" by the former, who repaid the compliment by sampling Kanye's "Flashing Lights". And West's post-Katrina anti-Bush outburst was pure Gil.

Common

The Chicago rapper collaborated with both Gil and West on "My Way Home" and "The People", and his vocal style – speak softly, but carry a big stick – is straight out of the Scott-Heron handbook.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments