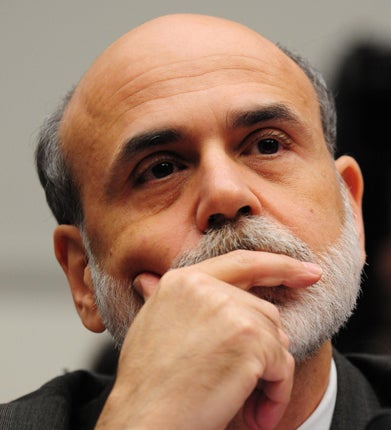

Bank on him: Ben Bernanke

He went from the prestige of Princeton to being the face of the Fed. Now the cerebral banker has a second term to prove his mettle

These are the disaster-strewn, dying days of the Age of the Nerds. No area of human endeavour has avoided their great soul-sucking project. We are all just harvested data to feed their overblown computer models, these great beeping, burping machines, oiled by slippery assumptions, from which they hope to divine the invisible truths about our world – and to predict the future.

For a generation, theirs has been the conventional wisdom. Political parties generate robocalls to voters according to their zip codes. Baseball fans, disciples of the sport's Sultan of Stats, Bill James, devote more hours to calculating his "Pythagorean winning percentages" than they do to savouring the sportsmanship. And in finance, once a profession characterised by testosterone-fuelled braggadocio, a generation of brilliant nerds built the models that provided a pseudo-scientific foundation for the tower of debt whose collapse has buried us all.

And yet the most powerful nerd on earth is still standing, as the sight this week of a relaxed Ben Bernanke at the side of Barack Obama in Martha's Vineyard attests. Bernanke, chairman of the Federal Reserve since 2006, has been reappointed for another term, something that looked distinctly unlikely when the new Democratic President prepared for power at the start of this year.

If it seems rude to describe the chairman of the US central bank as a nerd, consider this. Where other economists proceed from the gut, or with an ideological compass, Bernanke has always preferred to look for patterns in the data. It is a penchant he applied not just to his academic work but also to his hobbies – and to his friends. He once said you can calculate a lot about a person by noting how early they get their keys out of their pocket when approaching their front door.

An avid baseball fan, he is fascinated by the work of James, the eccentric writer and nerd-in-chief who invented "sabermetrics", a discipline which insists that by mining oceans of data you can scientifically explain why teams win or lose – and can adjust your team's strategy accordingly. Bernanke once gave one of James' books as a gift to then-treasury secretary, Hank Paulson, as they struggled to understand the unravelling credit markets.

The Fed chairman calls himself "a Great Depression buff, the way some people are Civil War buffs". His work with statistical data explained how governments' failure to fix a banking crisis led directly to the depression, making him the world's foremost scholar of that godforsaken period. As he battled a modern-day financial crisis at the helm of the Fed, his old Essays on the Great Depression made it into the book charts last year – but few of its readers successfully ploughed through its dense mathematics.

The seductive appeal of the nerd is their promise of objectivity, their apparent freedom from political bias. Bernanke's party affiliation – he is a Republican – had played so little role in his academic work that his appointment by President George W Bush surprised even quite close acquaintances. President Obama, beset by bigger political difficulties, could hardly afford to squander time and capital on a congressional fight to get a more partisan figure like Larry Summers, his chief economic adviser, into the Fed seat, as he had intended to do back in January.

In contrast to his colourful predecessors at the Fed, such as the 6ft 7in Paul Volcker, in and out of government roles all his life, or the wizened wise man Alan Greenspan, a prophet of laissez-faire economics, Bernanke looks the quintessential technocrat. Friends and acquaintances invariably describe him as "mild mannered" or "soft spoken", even "nervous", which is all true. But these descriptions miss a steel in him, an ambition and a will to succeed, and an uncommon ability to position himself for the job he wants, as he has just managed to do again.

Oh, and he saved the entire financial system.

Ben Shalom Bernanke was brilliant at an early age. Born in 1953 and raised in the little town of Dillon in South Carolina, he was reading while in kindergarten and skipped straight in at the second year of elementary school. Aged 11, he went to Washington to compete in the national spelling contest. (He was tripped up by the word "edelweiss".) He taught himself calculus in high school, scored the highest test results of any teenager in the state, and won himself a place at Harvard University. By 31, he was already a tenured professor at Princeton.

The young Bernanke's mother, a former schoolteacher, worried that he would be lost at Harvard. You don't have the right clothes, she told him. Bernanke's father had arrived in the US in 1941 with his family, refugees from the horrors of Eastern Europe, and the Bernankes were one of the few Jewish families in Dillon. His grandfather set up a corner drugstore where his father worked; the young Bernanke waited tables to pay his way through Harvard. He met Anna Friedman, his wife of more than three decades, on a blind date and followed her to Stanford, where she was studying Spanish. The couple have two children, and Bernanke paid tribute to his family this week. "They've supported me through the ups and downs of public service, and I hope they'll bear with me for just a few more years." It was heartfelt: in 2005, Anna had burst into tears when her husband first won the Fed chairmanship, knowing their life would never be the same again.

It was a complex computer model that first brought Bernanke to political prominence. In 1999, as economists were debating how to respond to a dotcom boom that had reached irrational proportions, he and a colleague presented a paper that used computer simulations to show that the Fed would be better off targeting inflation and leaving supposed "bubbles" well alone. The reaction was intense, the coverage widespread – and Bernanke liked it. He was suddenly on the political radar, and was soon appointed to the board of the Fed. Later, as head of the White House council of economic advisers, he told President Bush that he would offer a view on candidates to join the Fed board, but not on candidates to succeed Alan Greenspan as chairman. It was a subtle but firm indication that he wanted to be considered.

What follows is a tale of two Bernankes: Bernanke the Nerd vs Bernanke the Hero, and it was early last year when the first gave way to the latter. In 2007, the US banking system began to wheeze under the strain of too much mortgage debt handed to too many indigent borrowers, and confidence drained from the financial system at an ever-increasing pace. Last year was studded by a series of panics, each bigger than the last, first taking down Bear Stearns, the storied investment bank, then Lehman Brothers, then threatening to engulf everything else.

What Bernanke's academic work had taught him was that if the banking system seizes up, economic hardship is sure to follow. Knowing this, the chairman threw out the Fed's historic rulebook, inventing more and more new ways to flood the system with money. When the Fed ran out of ammunition, Bernanke stormed to Capitol Hill. The wild-eyed Paulson expressed his fears of panic in the streets, food shortages and martial law, and went down on one knee to beg Nancy Pelosi, Speaker of the House, for support; the calmer Bernanke, secure in his academic credentials, said the same in more moderate tones: if Congress doesn't promise to bail out the banks, there won't be a financial system left by Monday morning. "I kind of scared them," he said later. "I kind of scared myself."

Throughout the crisis, Bernanke and his aides worked around the clock to contain the catastrophe. It was only this month that he took two days off, his first holiday in two years, to attend his son's wedding.

In rewarding Bernanke the Hero, President Obama chose to ignore the questions over Bernanke the Nerd, questions that future generations of Bernankes will be debating. That first Bernanke was a man who declined to identify the US housing market as a bubble and then said its bursting wouldn't cause any wider problems, who sat at Greenspan's right hand as the guru decried the idea of regulating sub-prime mortgage lending and kept interest rates at levels that only stoked the mania.

It is the words of the people closest to you that wound the most. A note of congratulation from his erstwhile Princeton University economics department colleague Paul Krugman came with a sting in the tail for Bernanke. The Dr Dooms of the dismal science were the prescient ones, the likes of – yes – Krugman himself, who predicted the return of depression economics. And yet it is Ben Bernanke who emerged, blinking, into the Martha's Vineyard heat.

The reappointment seemed to Krugman to be "a reaffirmation of Serious Person Syndrome, aka it's better to have been conventionally wrong than unconventionally right".

A life in brief

Born: 13 December 1953, in Augusta, Georgia.

Early life: Raised in Dillon, South Carolina. Graduated summa cum laude with a BA in economics from Harvard; PhD from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Career: Taught at Stanford Graduate School of Business from 1979 to 1985; later visiting professor at New York University. Became a tenured professor at Princeton at the age of 31. Sat on the Board of the Federal Reserve 2002-5, and chairman of the President's Council of Economic Advisers 2005-6. Chairman of Federal Reserve from February 2006.

He says: "Economics has many substantive areas of knowledge where there is agreement, but also contains areas of controversy. That's inescapable."

They say: "Ben approached a financial system on the verge of collapse with calm and wisdom; with bold action and outside-the-box thinking." President Obama

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks