Death, Brutalism and pre-pubertal sex: Jonathan Meades embraces some difficult subjects in his TV series and memoir

The second episode of Meade's new BBC series - Bunkers, Brutalism and Bloodymindedness: Concrete Poetry - airs tonight and in May he publishes An Encyclopaedia of Myself, his first volume of memoirs

'I like doing different things. I never wanted to be one of those people who sat down and every two or three years a new novel comes out. Very few can bring it off and say anything interesting. Some people like Burgess or Nabakov, but they are geniuses. An awful lot of writers churn stuff out and you wonder why they are doing it. They can’t even be making much money.'

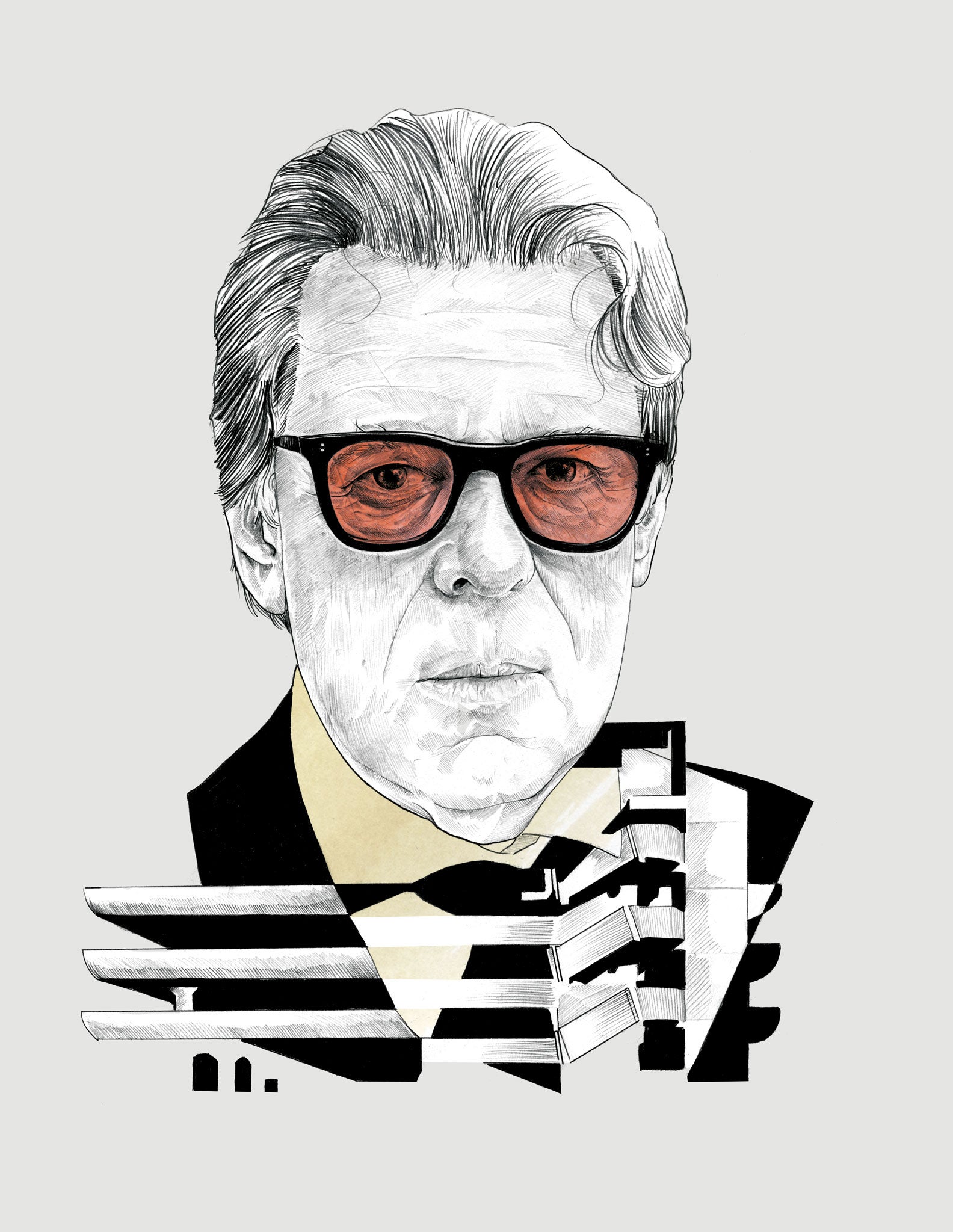

So says Jonathan Meades, whose sluggishness as a novelist – his most recent, The Fowler Family Business, came out more than a decade ago – has been more than compensated for by a torrent of those "different things". Meades the journalist, Meades the architecture critic, Meades the food writer. Meades the maker of idiosyncratic documentaries about idiosyncratic places and buildings, Meades the part-time photographer and painter, Meades the one-time actor. Meades, the sunglasses-wearer extraordinaire.

Now 67, his recent activities suggest that age has not withered his infinite variety. Last year ended with two major releases: something old, something new. Pompey, his gloriously sordid novel about a priapic fireworks manufacturer, was re-published to mark its 20th anniversary, complete with encomiums from Stephen Fry and Simon Heffer. This was followed by Pidgin Snaps, a collection of his occasional photography released as a set of postcards.

So far, 2014 suggests that, if anything, he is picking up the pace. The second episode of his new BBC series – Bunkers, Brutalism and Bloodymindedness: Concrete Poetry – airs tonight (the first is still available to watch on the BBC's iPlayer). In May, he publishes An Encyclopaedia of Myself, his first volume of memoirs.

"It's not a particularly flattering portrait of a child, insofar as it is a portrait of my childhood." he says. "There's quite a lot about pretty gruesome pre-pubertal sex. You don't think, 'Oh what a lovely little fellow.' It's kind of the opposite of a misery memoir. I was quite happy. It's about a child who is curious. Precocious isn't the right word. I was a tiresome know-all."

Something of the curious know-all remains in Meades' adult self, although now it is leavened by charm, wit, learning and prodigious eloquence. Just when you think you have found a subject he won't like – football, say – or one he must surely be bored by – the weather – he expounds expertly on the form and vexed internal politics of his team, Southampton FC, or offers a brief history of Le Mistral. Other topics range from François Hollande's political hinterland to the wisdom of dredging rivers, Proust to English literary outsiders such as Geoffrey Household.

Meades is a hard man to contain, both professionally and conversationally. We talk on two separate occasions for a total of almost four hours. First, over breakfast in London, where Meades has been editing his new TV series; then a "brief" chat on the phone, which extends to almost two hours. Brutalism inevitably plays a part – Meades talking from the apartment in Marseilles's Unité d'Habitation, designed by Le Corbusier, where he lives with his third wife, Colette.

From Second World War bunkers around Marseille to neo-Brutalist masterpieces such as Will Alsop's Conseil Général des Bouches-du-Rhône (the "Grand Bleu"), Meades has traced Brutalism across Europe. He talks with awe about filming anti-aircraft flak towers in Vienna – "They are extraordinary. You look down a street of five- or six-storey apartments, and then you have this huge thing looming over them, completely mute. A kind of void" – and contends that Brutalism's moment has finally arrived, after decades of often ignorant and contemptuous dismissal.

He points to a new generation of architecture critics – Owen Hatherley, Douglas Murphy, Kieran Long – who find the movement's forbidding presence a refreshing antidote to the feeble predominance of "Ikea Modernism". "They have grown up at a time when architecture has been very, very insipid. A main aspiration of architects over the past 40 years has been not to give offence. There is a terrible timidity, whereas Brutalism was very aggressive. It was anti focus groups and consensus. The architects were ahead of their time and it has taken half a century for people to see that this stuff was done with spirit and invention."

Meades concedes that Brutalism has been unpopular in the past: buildings such as the Tricorn in Portsmouth have been demolished, while Keith Ingham and Charles Wilson's Bus Station in Preston only narrowly escaped the same fate. "The fact that town councillors and planners have mostly hated [Brutalism] proves how good it is. Who would want to have the taste of some provincial councillor or dreadful planner? You don't go knocking down Stonehenge or Lincoln Cathedral. I think buildings like the Tricorn were as good as that. They were great monuments of an age."

A mention of Prince Charles, a prime antagonist of Brutalism, is met with a heavy sigh. "He's crass, and a counter-indicator. He said the Tricorn looked like 'mildewed elephant droppings', which is coarse and a visually inept simile. If you look at elephant droppings, they make a particular shape. There are probably buildings that look like that. The Tricorn most certainly didn't."

Brutalism is an eminently Meadesian subject: uncompromising, thought-provoking, challenging and just a little scary. "There is something about being excited by this stuff which is terrifying and slightly sinister that I find very appealing. I don't like the saccharine qualities of hollyhocks and thatch at all. I find it really rather dismal. The English have such a thing about prettiness – not even beauty. A lot of Brutalist buildings really are sublime in the way Edmund Burke specified – they have to terrify. As Mr Ron Atkinson says, it takes no prisoners."

One could, perhaps, say something similar about Meades himself, whose on-screen persona echoes Brutalism's impersonal froideur. Standing nonchalantly against carefully framed backdrops wearing his trademark sunglasses and undertaker's couture, he knits bons mots into dead-pan commentaries on British people and places. This performance, at once urbane and outré, has established Meades as the thinking couch-potato's scourge of the drab, the orthodox and the preconceived. "Just look", he urged in 2013's The Joy of Essex, as startling images of the county's arcane glories made mincemeat of our laziest preconceptions.

Meades accepts, albeit reluctantly, that his films jostle these commonplaces. For the most, he says, the viewers don't really enter into it. "To think of an audience in terms of A-to-Bs, I find unbelievably patronising. It's one of the reasons that television is so terrible, so lowest common denominator. Everyone is trying to be accessible. But accessible to who? If it's going to be accessible to everyone, it has to be unbelievably low level, which means more intelligent people won't watch it. The whole idea of populism is inherently flawed." The more he talks, the more tempting it becomes to join the dots between Meades' advocacy of Brutalism and Meades himself.

Work began on his Unité d'Habitation home in 1947, the same year that Meades was born. Both were formed by what he calls an "unfashionable" post-war age – one that mixed frankness, ambition, fear and a lack of sentiment. "It was a harsher world, with a harsher architecture. There was nothing green about [Brutalism]. It was kind of anti-green. It didn't have these religiose pieties attached to it. It was the time of high seriousness: the Cold War. We had dropped bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki There was hubris, but there wasn't a desire to please, or simperingly apologise for anything. It is very different from cosying up to a meadow."

Meades grew up in Salisbury: after serving in Iraq during the war, his father was a sales rep for a biscuit company; his mother was a teacher. He describes his hometown as tough but in constant transition, thanks to its large military population. "It had Porton Down chemical warfare, and Boscombe Down experimental aircraft. There was a hard-drinking machismo about those who stayed on in the Army [after the war]. Anyone would slap you. Education was not child-centred. It was sadist-centred," Meades recalls. "People were much tougher. They were routinely rude. People didn't bother to be nice because someone was left-handed, or gay, or had red hair. You would say, 'He's a left-handed queer with red hair.'"

While the memoir resists any form of self-analysis – "The impetus is that Flaubertian one: 'Describe, describe, describe'" – one can glimpse how Meades' mature eclecticism was formed by Salisbury's ever-shifting nature and a juvenile need to evade boredom. One can also detect the familial roots of a bleak world view.

"The strain in everything I write, of not being taken with the bounteousness of humankind, was also the attitude of both my parents. They didn't have a particularly high opinion of themselves, or their fellow men and women. They were both reasonably happy, but they were both mistrustful of any kind of 'ism' that was dependent on the perfection or near-perfection of humankind. Socialism basically doesn't work because humans aren't sufficiently altruistic to make it work. Which is kind of how I think about things too. When I was at Rada, I was the only student who read The Daily Telegraph."

Lately, Meades has found the bleakness harder and harder to avoid. "There is a lot of death," he says of An Encyclopaedia of Myself and his new project, a novel-in-progress. "My editor noticed a lot of suicide. It hadn't occurred to me but there is. The immanence of death is omnipresent in the book."

He recently made a grim inventory of friends and colleagues of his generation who have died in recent years. "It was over 30," he says with considerable disbelief. "We were meant to be living longer than our parents, but I can't remember so many of my parents' friends dying quite so young. They are all very different cases. Car crashes, suicide, drink and drugs, drink, drugs, cancer, cancer, cancer, cancer."

When I ask about his own fears that he may cease to be, Meades sounds coolly accepting. "What do I think about death? That it is going to happen. Get over it. I do think about death on a daily basis, but I think that is what distinguishes us from animals."

This same frankness means An Encyclopaedia of Myself promises to be both enthralling and possibly too honest for its own good. Pompey had its skin-crawling moments, but that was fiction. Does Meades have any apprehension about removing his figurative sunglasses and revealing himself so candidly? His response would do a Brutalist building proud.

"No," he replies after a moment's thought. "It's important to develop a rhinoceros hide.Sure, you are exposing yourself. But I don't really care any longer. I think one of the reasons I didn't write a memoir years ago is I was too worried about what people might think. Now, I don't really give a toss."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments