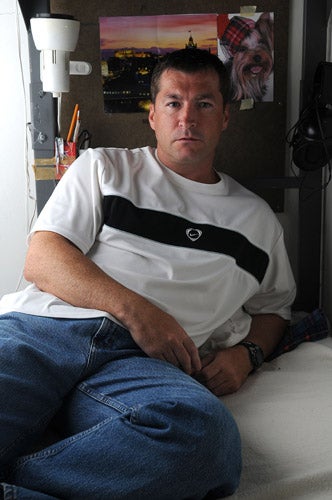

First Person: 'I will spend the rest of my life in prison'

Tom Richey, 39

In 1987, Scottish ex-pat Tom Richey pleaded guilty in America to shooting two people while high on LSD. Now serving life for murder, Richey explains the effect his sentence had on his relationship with his father.

I know dad blamed himself for my predicament. I think every parent with a son or daughter in prison blames themselves and wonders where they went wrong. But I never blamed my dad for what I did, I blame myself. I ingested LSD. I carried a gun. And I pulled the trigger.

I received a sentence of 65 years, and soon found myself drowning in a foreign prison environment, thrashing to keep my head above it all, especially after the Washington officials denied my application for transfer to a Scottish jail.

I lost hope. I think my dad sensed this, so made the decision to travel 2,000 miles from Ohio, where he lived, to Washington State. He settled in Washington to be near me, always ready to accept my phone calls or to visit. I certainly didn't deserve his loyalty because I destroyed the promise he invested in me when I insanely destroyed the lives of others. But he stuck by me anyway, and he rescued me from being smothered by the American prison culture, from being isolated thousands of miles from home. He saw in me what others didn't, and he nurtured that, gave me encouragement and direction. He became a great father, and along the way, he became my best friend.

Dad died on 8 April 2009. His death wasn't unexpected. He'd been diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2005. But I'd seen him fade a few years before the cancer.

Before he moved to Washington State, dad would drive five hours to visit me in prison at least half a dozen times a year, and each time he came, I saw less of him. Old age rusted the spring in his step, and it began to dismantle his memory, his quick wit, and sometimes his eyes showed the growing fear of a man who knew age was slowly ravaging him, taking away his capacity to live, to be the man he was.

Dad was never afraid to show his emotions, and always at the end of our visits, his eyes would soften with moisture, and I'd see the longing of a father who wished he could walk his son out that prison gate with him. I'd hug him tight, wishing I could go, wishing I could relieve his pain.

As the years passed, and I struggled to prove myself as a writer against a wall of publisher bias, I became discouraged and considered giving it all up. But dad confided that he wanted to hold a book I'd written in his hands before he died. If I achieved nothing else in life, I at least wanted to fulfil that dream for him, this man who sacrificed so much to move to Washington to save his drowning son.

Finally, in 2005, my book about my brother, who is on Death Row, was published: Kenny Richey – Death Row Scot. I remember the pride swelling from my dad when he visited after receiving a copy of the book. He looked upon me with a look I'd never seen before. Admiration. I was a grown man but felt like a boy again, awash in my dad's favour. A son can know no better feeling than that.

But I know dad harboured another dream. He wanted to see me free. Neither of us said so, but we both knew he'd never be alive to witness my freedom. Time wasn't on our side. We last spoke on 4 April. It was a Saturday morning. Our conversation was brief, he told me he loved me, and that we'd said everything we wanted to. I could hear him struggle to push his words out. I told him not to worry about me, that I wouldn't give up; he'd prepared me well for life ahead.

On 9 April, I lost my best friend. I lost my anchor. I miss my dad, but I also embrace the world alone with the tools that he left me.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies