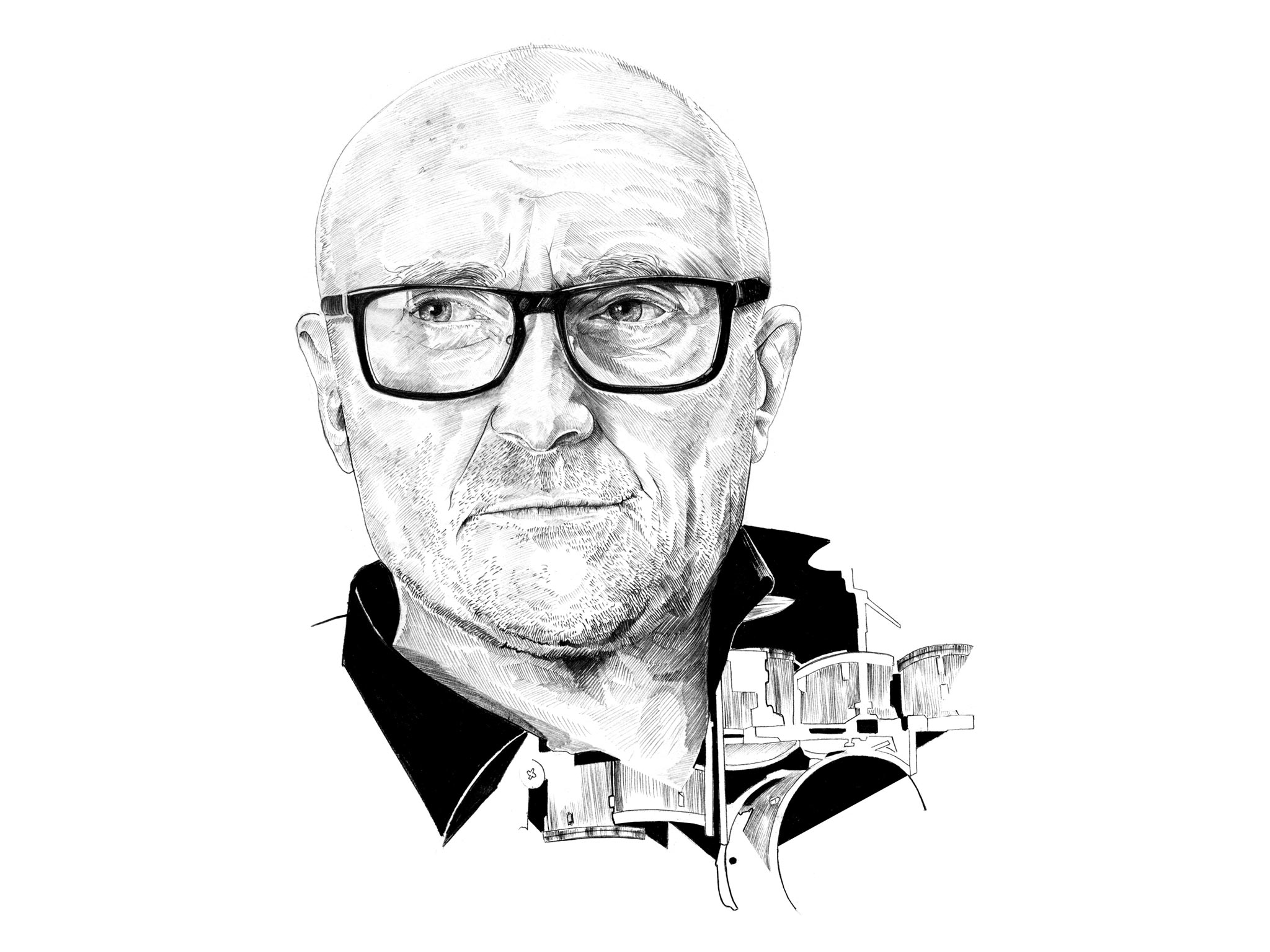

Phil Collins: The King Lear of pop music

He’s the rock god who refuses to retire. Perhaps he’s still searching for the critical acclaim he feels he’s been denied

The music world was startled by two pieces of news this week. First, that Phil Collins, the drummer-superstar, had died. A convincing-sounding Facebook page “RIP Phil Collins” attracted a million likes, until, on Wednesday, it was declared a hoax. The other news was almost as startling: “Rock band Genesis are to reunite for the first time in nearly 40 years”, under a picture of the band members from the classic 1970 line-up posing together for the first time since 1998, in their bald and grizzled sixtysomething prime.

The thought of being able to see Tony Banks, Phil Collins, Peter Gabriel, Steve Hackett and Mike Rutherford on stage together again is enough to make the hearts of prog-rock disciples burst. Luckily, it isn’t going to happen. The band are “reuniting” for a BBC2 documentary called Genesis: Together and Apart. “There are no plans for Genesis to reform or anything like that,” the band’s gruff, patriarchally bearded manager Tony Smith told me. “They got together in one room to do an interview. They have no collective plans on the horizon – or any horizon, no matter how far away.”

That’s clear enough, isn’t it? Except, when it comes to Phil Collins, it isn’t. The band’s drummer, singer and richest member has a habit of hinting that it’s not all over for Genesis – or himself. He’s flirted with retirement many times, telling the band that it’s all over, telling the world he’s spending more time with his family, before bouncing back, full of enthusiasm. The last album he made with Genesis was We Can’t Dance in 1991. In 1996, he told the other members: “I think I’m going to call it a day.” But in 2007, he, Banks and Rutherford were back on stage before 500,000 fans in Rome for the Turn It On Again tour.

In 2011, he officially retired. His hands were affected by a dislocated vertebra in his neck, and his drumming suffered. And he was deaf in one ear. It was all over. Then, last November, he blithely told German media: “I’ve started thinking about doing new stuff… some shows again, even with Genesis. We could tour in Australia and South America. We haven’t been there yet….” A month later he told the Miami press: “I’ve got some lyrical ideas on paper that are good. I’ve started to thrash around at the piano.” More recently he’s talked about writing music for the singer Adele. Friends describe his habit of ringing up to announce that he’ll be back on tour imminently – only to ring later to say he’s changed his mind.

Do Genesis know about his hints at reforming? Have his drumming hands magically recovered their power? What’s going on with the King Lear of music – the man who just cannot retire?

Two impulses seem to drive Collins now. One is the burden of his success. As Genesis member and solo artist, he’s a phenomenon. He’s won six Brit Awards and seven Grammys. He’s one of only three musicians – the others being Michael Jackson and Paul McCartney – who have sold more than 100 million as both a solo act and in a band. His total worldwide sales as a solo act are 150 million. In his heyday with Genesis, 1981-1990, if you factor in his solo stuff, he had more Top 40 hits in the Billboard Hot 100 than any other artist. He’s also written music for the movies and has an Oscar and two Golden Globes in his New York home. He has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Not bad going for a kid from Middlesex. But it leaves him with a desire to round off his career with – what? What would be sufficiently awesome to be the final hurrah of Phil Collins?

The other impulse is to be praised by his own country. Collins is sensitive to criticism of his work, his songs, his supposed blandness – and his status as a tax exile. British critics have always claimed that his metallic stylings, and “gated reverberation” drum sound, produce expressionless music. A misconception that he supports the Conservatives has stuck to him for years like a burr on a horse’s flank, as has the rumour that he dumped his second wife by fax. Despite his millions, he doesn’t feel loved at home. His retirement letter in 2011 trembled with hurt-puppy tristesse. “I don’t really belong to [the MTV] world and I don’t think anyone’s going to miss me. I’m much happier just to write myself out of the script entirely. I’ll go on a mysterious biking holiday... and never return. That would be a great way to end the story, wouldn’t it?”

The story began in January 1951, when Philip David Charles Collins was born in Hounslow. His father was in insurance, his mother a theatre agent. He started playing drums at five, playing along to the television. A successful child actor, he played the Artful Dodger in Oliver! on the London stage, and a screaming teen extra in the Beatles film A Hard Day’s Night. At Chiswick Community School, he formed the Real Thing and, two bands later, at 18, he was in Flaming Youth whose 1969 album Ark2 was praised by Melody Maker. In 1970, he answered a classified ad in the magazine for a drummer, and auditioned at Peter Gabriel’s family home in Chobham, Surrey. Arriving early, he was sent for a swim in the family pool while other stickmen were inspected; when it was his turn, he’d memorised the audition part and nailed the job.

“We weren’t on the same planet as Phil,” Mike Rutherford wrote in his memoirs. “He always had a bloke-next-door, happy-go-lucky demeanour about him: let’s have a drink in the pub, crack a joke, smoke a cigarette or a joint.” The Middlesex roustabout and the Charterhouse schoolboys nonetheless forged a strong alliance and produced classic albums: Nursery Cryme, Selling England By the Pound, The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway. When Gabriel left to go solo, Collins was chosen to handle vocals. The new-look Genesis’s first waxing, A Trick of the Tail, wasn’t just successful; it brought them an American audience. Successive 1980s albums – Duke, Abacab, Invisible Touch – brought millions in revenue, while Collins embarked on a solo career.

What spurred him was rejection – he began writing songs when his first wife, Andrea Bertorelli, left him. His first solo album, Face Value, introduced the world to his best-known song, “In the Air Tonight”, where the walloping drums kick in two-thirds of the way through. The follow-up album, Hello! I Must Be Going, spent a year in the UK charts, and one track, his cover of “You Can’t Hurry Love” was his first No 1 hit. He sang and played drums on “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” by Band Aid – and at the Live Aid mega-concert in 1985, he contrived to perform at both Wembley and JFK Stadium in Philadelphia, with the help of a Concorde flight.

His third solo effort No Jacket Required went to No 1 in the UK and US – and led to the first murmurs of criticism that he’d become too safely embedded in the middle of the road.

Now in his fifth decade of performing, Collins at 63 has a personal fortune of £115m; according to The Sunday Times, he’s in the top 20 wealthiest people in the music business. His voice has dropped an octave over the years but sounds fine. His restless desire to get back into songwriting and public performance is compromised by issues about his health, his hands, his deafness, and the depression and lack of self-esteem from which he’s occasionally suffered. But he still wants to get out there: to confront his critics, and end with a bang. Learning that the world thinks he’s dead would only spur him into action.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments