'Queer saint' Peter Watson left his mark on British culture by bankrolling artworld giants

British culture owes a huge debt to Peter Watson. Cecil Beaton's 'queer saint' bankrolled all the famous names, from Spender to Freud, and co-founded the ICA. But as a louche sex life hinted, he was a damaged soul

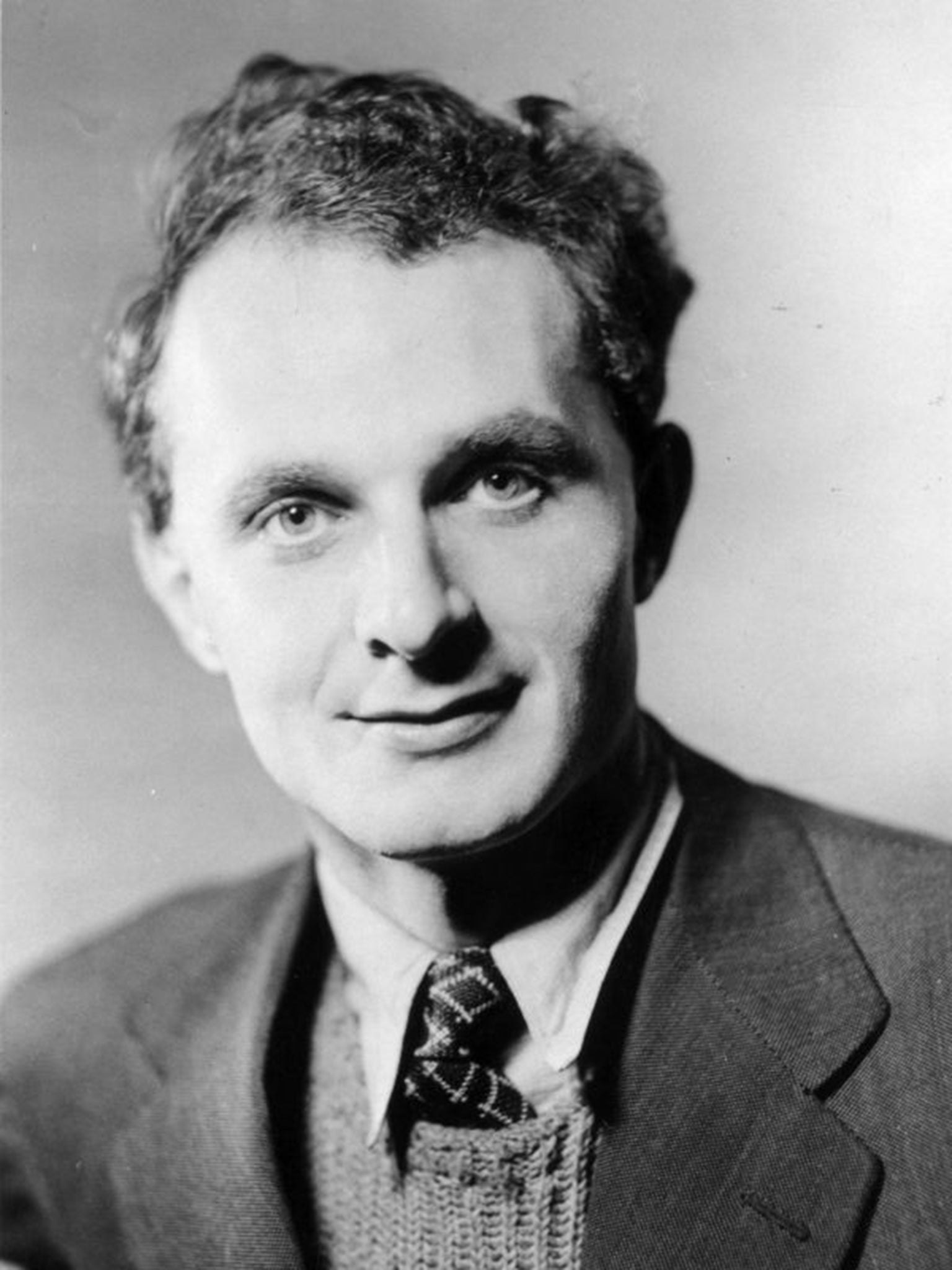

Look over the shoulders of the headline figures of the mid-20th-century British cultural world – from Cecil Beaton and Stephen Spender to Cyril Connolly and Lucian Freud – and you will find, standing behind them, a languorous, attenuated man with deep-set eyes and a feminine mouth. This man, Peter Watson, is now largely a footnote to the lives of others – a bright young thing who gradually sloughed off some of his sparkle to become an artistic patron and who died in mysterious circumstances aged 47. Without him, though, the British art world would have been a very different place.

Watson was a collector – of beautiful things, of beautiful people and, most consistently, of people in whom he saw a talent for creating beauty. He was among the first in Britain to sign up wholeheartedly to Continental Modernism and he bought works fresh from the studios of Picasso, Miro, Giacometti, Klee and Dali; he sponsored composers and loved jazz; he was a founder of the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London; he bankrolled young British painters such as Freud, Francis Bacon and John Craxton; he put up the cash for the highbrow literary-cultural magazine Horizon, whose contributor list is a roll-call of British arts and letters (Christopher Isherwood and WH Auden, George Orwell and Graham Greene, Bertrand Russell and Virginia Woolf). And he doled out cash to a motley collection of greedy or impecunious hangers-on on the fringes of the cultural scene.

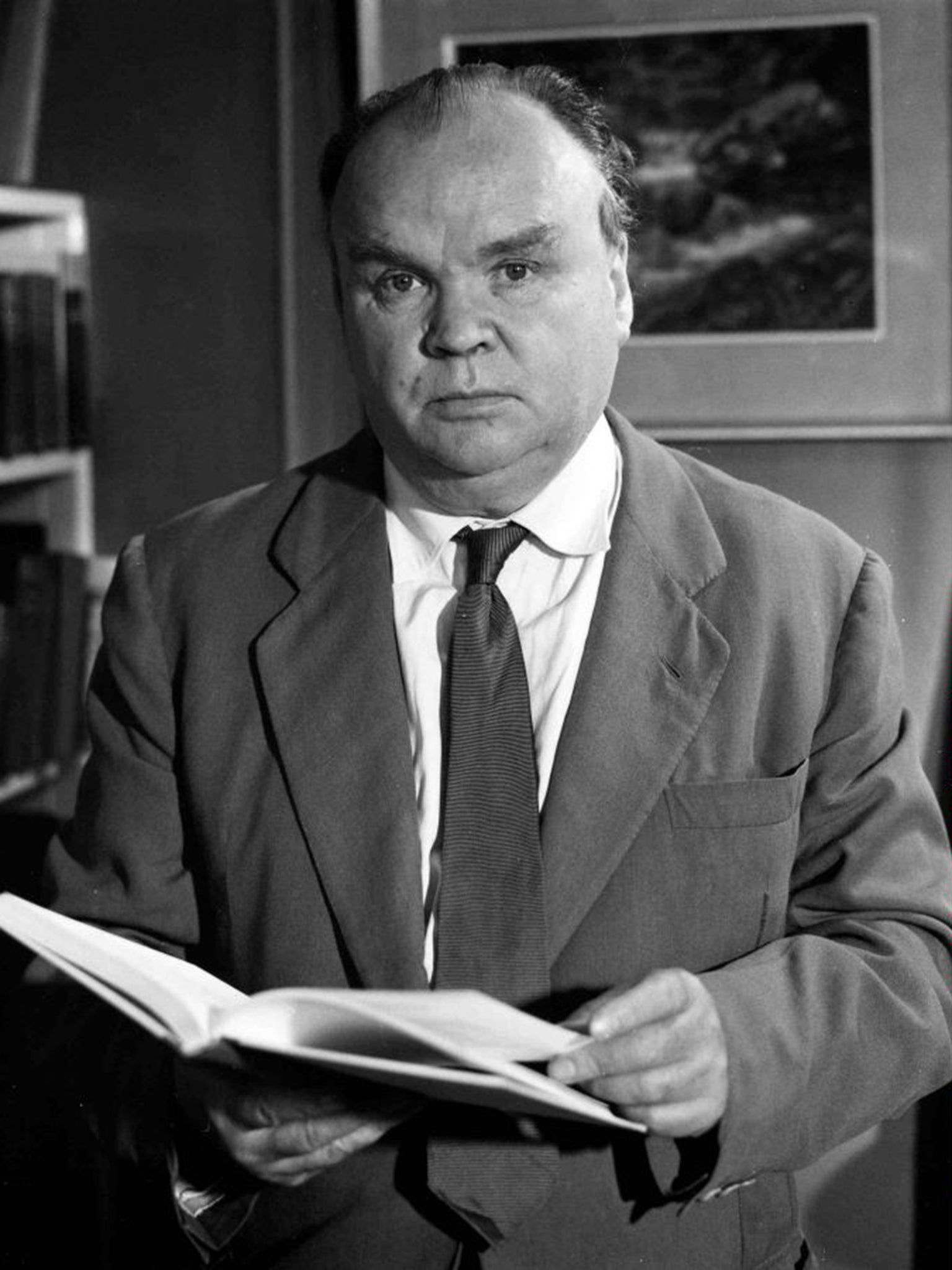

The curious life of this curious man is the subject of a new book, Queer Saint by Adrian Clark and Jeremy Dronfield. Watson was queer in both senses and the authors trace his wanderings through both the beau monde and the dingy one and lay out the friendships and loves he found in each. The figure that emerges is at once a gay playboy with a taste for rough trade and an aesthete in the purest sense of the word who left an indelible if largely unacknowledged mark on British art.

What allowed Peter Watson to be these two people simultaneously was money. He had the great good fortune to be one of the richest men in England, courtesy of a £1m trust fund that in 1930 generated the huge sum of £50,000 a year. Gore Vidal – always so good at isolating the salient characteristics of both friends and enemies – later described him as "a charming man, tall, thin, perverse. One of those intricate English queer types who usually end up as field marshals, but because he was so rich he never had to do anything."

To Watson's eternal embarrassment the money came from margarine (pronounced, when Watson was born in 1908, with a hard "g"). His father came from trade and had finessed his dairy businesses into a huge fortune, some of which he spent on a vast country estate at Sulhamstead Abbots near Reading and some on easing his way to a knighthood and having a tilt at a barony. When at Eton, among the old money, the young Watson still sensed the tang of margarine in his elegant nostrils.

He was the youngest of three children, by a decade: his brother, though outwardly more respectable, was also gay, while his sister grew into a county lady whose interests were in animal rather than male flesh – namely, Irish wolfhounds and racehorses. Watson had little to do with either sibling, his mother being the sole family member to whom he felt either loyalty or affection.

At Eton he quickly found himself in the homoerotic and fey but high-minded cultural milieu he never really left. Contemporaries included Orwell, Anthony Powell, Ian Fleming and James Lees-Milne. He already saw the world as a rather dull place: "Nothing is more awful than too much reality – I must say, I'd rather have a little fantasy for myself than all this dull reality." With adolescent solipsism cranked up by wealth, it never occurred to him that he knew nothing about reality whatsoever.

There was not much reality to be found in Oxford, either. When he went up to St John's there was still a hint of the Brideshead generation around and Watson was neither a sportsman nor a scholar. He studied, in the loosest sense, for two undistinguished years, during which he failed almost every exam possible but added Auden, Isherwood and Spender, among others, to his burgeoning list of friends.

Oxford and Watson gave up on one another in 1930. He was sent down and did what many a feckless young man blessed with vast resources and no motivation to do much beyond seeking pleasure would do: he flitted. It was on a butterfly jaunt to Europe with the stage designer Oliver Messel that Watson was introduced, in Vienna, to Cecil Beaton. Neither man found the other particularly prepossessing: Beaton, already an up-and-coming photographer, described Watson as a "tall, gangling young man, with the face of a charming codfish". Beaton rapidly, however, discovered pescatarian tastes and Watson became the love of his life.

As the relationship developed, Watson kept the upper hand over the effete and social-climbing Beaton. Their friendship was warm to the point of simmering and tactile but, much to the photographer's frustration, never consummated. Beaton would lie on Watson's bed and stare at him while he slept, he would caress him and tickle his feet, they would go in for a bit of breathless and squealing "wrestling", but there Watson would draw the line.

When they gadded around Europe together, Watson indulged himself with the boys he found in the boîtes in Paris and the bars and beer halls of Munich and left poor Beaton bubbling away. "Celly-boy", as Watson called him, was love- and lust-struck. "Peter," he said, possessed a "beastly beauty that is subtle… and his buttocks, leanness and long, stringy legs and arms, buttery neck and big hands make for me the ideal".

Beaton gave Watson every opportunity but he never took it. They travelled to America together, where Beaton had work to do for Vogue, tucked up together in a ship's cabin. They toured the Caribbean and Europe. They wrote as lovers, spoke as lovers, discussed art as lovers (Watson, in the middle of an early-German art phase, to Beaton: "Do you think a nice crucifixion scene for the dining room?"), but they never became lovers. After many years, Beaton eventually came to realise that his longing was destructive and by sheer force of will forced himself to step back from their intimacy in order to preserve his own sanity. He never managed to excise Watson completely, though: it was he who called him a "queer saint"; and when he received news of Watson's death, he admitted: "I have been crying like a hysterical child most of the day and night."

Watson himself was not immune to love and fell for a dreamy-eyed American courtesan called Denham Fouts (known as "the best-kept boy in the world") whom he met in a Berlin nightclub. Fouts was Watson's "dark angel", who had seduced a string of rich male lovers and would later add Truman Capote to his tally. He was a drug addict and waster who nevertheless had the perspicacity to see that Watson's "greatest need is to love rather than be loved". Fouts, who once went to a Cocteau play in Paris dressed in pyjamas and a fur coat while clutching a bottle of brandy and a silver cigarette case, was Watson's great love – needy and high-maintenance payback, perhaps, for his treatment of Beaton. He paid for him and felt responsible for him up to Fouts's drug-induced death on a toilet in Rome, where he had decamped with a new lover.

The second driving force in Watson's life was art. Never keen on London, in 1938 he installed Fouts and himself in an apartment in Paris and filled it with the best modern paintings he could buy. His timing was poor: with the Nazi invasion, he decamped back to England and left his pictures in the care of a Romanian art critic called Sherban Sidery, who most likely tipped off the SS about the cache. The pictures were appropriated, though after the war Watson came across several on sale in the galleries of dealer "friends", all of whom predictably protested their innocence.

Back in London, Watson's war efforts were centred on Horizon, with Cyril Connolly as editor. It was Watson's money that funded the magazine but, as he wrote to Beaton: "What this country needs is more and MORE Art, otherwise Life is not worth the trouble. These are my war aims." Their work on the magazine exempted Watson and Connolly from conscription and Nancy Mitford, less than generously, thought this was their intention. In fact, Watson was called up, in 1941, but he was rejected for being too spindly.

The war, and the Blitz in particular ("I never go to a shelter – I would rather die in my sleep"), fostered a deep and unexpected admiration in Watson for the British people. He thought, though, that their taste in art was execrable. It was this that lay behind his work for the ICA, which he helped to establish after the war. He saw it as an institution to educate the public in modern art and worked hard at putting on exhibitions by protégés such as Freud and Bacon.

Such good works did not stop him from becoming a person of interest to the intelligence services when Burgess and Maclean, on the point of being unmasked as Soviet agents, decamped to Moscow. Watson had met both men through his Communist fellow traveller friends Auden and Spender, and he had been on MI5's radar since before the war. Watson, for all his wealth, had the occasional twitch of socialist feeling but he was never a Communist and there is no evidence he was a spy.

Post-war currency restrictions meant that when he picked up his old routine of travelling to America and round Europe again, he was forced to do so in less style than before – but he resumed the old hedonistic routine nevertheless. The casual liaisons continued but he also had meaningful affairs with two young Americans, Waldemar Hansen and a navy sailor called Norman Fowler.

Neither, though, could stop him descending into bouts of malaise at the state of the world. It was, he believed, a dreary, dispiriting place; and although the Allies had fought in defence of civilisation, Watson believed European culture had been another of the war's victims. The new art movements were confirmation; abstraction and expressionism, the leading styles, were, he thought, nothing but "decoration and narcissistic display". In 1946, he had protested that "I don't prefer art to life", but by the early 1950s both had lost their lustre.

The great wealth that had brought him deluxe toys from Picassos to a coral-coloured Rolls-Royce with fur seats (despite the fact that he was an appalling driver) no longer had the same effect. He lived in a small flat, without a car; Horizon had closed; the begging of his friends carried on, Hansen was needy, Fowler unreliable, and his once-formidable sex drive had dwindled to hand-holding. (As Stephen Spender had once noted, Watson was "essentially made for honeymoons and not for marriages".) Watson himself wrote that "it is very difficult to be happy unless you have a place in life". And he no longer knew what his was.

This Weltschmerz was brought to an end in unexplained circumstances. One night in 1956, a distraught Norman Fowler rushed into the street outside Watson's apartment in Rutland Gate, Knightsbridge, and accosted a policeman. Watson was in the bathroom, he gabbled, the door was locked, the tap was running and he wasn't responding to Fowler's calls. When the policeman broke down the door, he found Watson dead in the bath, the key on the floor.

The coroner's verdict was accidental death: however unlikely it seemed, Watson had drowned; and neither suicide nor murder was mentioned – despite the facts that Watson and Fowler had had a blazing row shortly before, and that Fowler was more than muscular enough to break down the door himself without needing a policeman to do it. The fact that Watson had left almost everything to Fowler in his will didn't seem to raise suspicions, either. In fact, Fowler rapidly sold the lot – pictures, objets, books (the sale of Watson's library was still going on two years after his death) – and disappeared to the Caribbean. In 1968, he too died in his bath in unexplained circumstances.

Watson, for all his money, had been unable to outrun reality after all. He had, though, spent to good effect as well as selfishly. Not only had he personally sponsored some of the most significant modern artists of his day but he had used his influence at Horizon and the ICA to foster a greater interest in contemporary art. He had been, too, a munificent if sometimes maddeningly inscrutable friend to a large coterie. Not every rich man can say as much.

He deserved a better fate than the one he met – and he had envisaged one for himself. At the outbreak of the Cold War, he said that "when the hydrogen bomb bursts, I want to disintegrate in… dust made up of Renaissance plasterwork, William Kent tables, Picasso, brandy and Alban Berg records". It would have been a more fitting end for this aesthete than whatever happened in that locked bathroom.

'Queer Saint', by Adrian Clark and Jeremy Dronfield (£25, Metro), is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments