Rob & Nick Carter: Old masters brought to life, in the blink of an eye

A new exhibition shows how technology can challenge our idea of a great work, as two-dimensional paintings become animated three-hour films with living, breathing subjects. Nick Clark meets Rob and Nick Carter

For centuries, art lovers have stood blinking in front of the Sleeping Venus by Italian master painter Giorgione, but few would be prepared for it to blink back.

Among the groundbreaking works by artists Rob and Nick Carter that go on display this week at The Fine Art Society is Transforming Nude Painting, which brings Renaissance masterpieces into the digital age. The Carters are at the vanguard of a movement that embraces old and new methods to create art – picture an image on a laptop screen framed by a Baroque gilt frame.

Of the Venus – who breathes and twitches – Rob Carter says that animating an old master work is "the perfect way for us to move forward. Our work has always been interested in fusing the analogue and the digital". His partner, Nick, adds: "Several years ago, people were worried about artworks with a plug. But now people are embracing technology like never before."

The married couple (Nick becomes Nicky at home in central London, where they live with their two daughters) have painstakingly recreated the original work of a nude Venus slumbering in front of a Venetian background and, using ultra-HD technology, have created a 140-minute piece that has been described as a "digital painting".

To create an extraordinarily complex work they turned to MPC, a British Oscar-winning visual effects company, who turned life model Ivory Flame into the sleeping Venus using green-screen technology. Her chest rises and falls, her hand moves and her foot twitches. Behind her, day turns to night, clouds move across the sky and the grass and trees ripple in a breeze thanks to computer-generated imagery.

"The Giorgione is a wonderful picture," says Nick. "We wanted to do a nude and what better one to do? It was very shocking and daring in its day. It will be interesting seeing people's responses to her." A sudden movement in one of their earlier paintings prompted one viewer to choke on a sandwich.

Art critic Alastair Sooke calls Transforming Nude: "Not only a spectacular lightshow for people to marvel at, but also a complex paradoxical work of art. It uses cutting-edge technology to masquerade as something old."

It is one of four animated old masters in the Carters' exhibition at The Fine Art Society in London, which opens this week, ahead of the Frieze art fair in London, a celebration of contemporary art that attracts collectors from around the world. Digital art will be a major feature of the fair.

The Carters' new body of work has been more than four years in the making. Kate Bryan, head of contemporary art at the gallery, says the pair "exploit all that is dynamic and groundbreaking in the digital age".

Nick Carter said the reworking of the old master reflects how images are presented today, "through the moving image, whether it's movies, TVs, phones or moving billboards. The old masters distilled reality through painting, making an image to bring home. The way we receive art now is very different."

Several of the works are displayed on Apple Mac computer screens and others on iPads, surrounded by a frame designed to emulate the old masters they reference.

The first of their digital paintings was Vase with Flowers in a Window by Flemish master Ambrosius Bosschaert. It took MPC several thousand hours to render, longer than a full-length feature animation film would require. Shown on a loop, the day becomes night, the buds open and close and their stems suck water from the vase, while inquisitive insects fly across the screen. "You could hear gasps when things happened," Rob said. "We knew then that we had achieved what we set out to do."

The digital art project was a first for Jake Mengers, creative director at MPC. "There was a lot of trial and error as nothing like it had been done before."

"Each work had unique challenges. Venus was tricky because it's such a huge picture and a mixture of live action and computer graphics. This is bleeding-edge technology."

Nick Carter explains why artists are embracing digital technology. "Art throughout history has used what has become available; you want to use the best tools. There's nothing wrong with oil on canvas but if you don't embrace what is available, art couldn't move on. It wouldn't reflect the world we live in now."

The artists hope the changing image will encourage the viewer to stay in front of it for longer, after reading a statistic that the average time spent looking at a painting in a gallery was six seconds.

"You have to look away and look back to realise things are happening," says Nick. "That was very deliberate. We wanted to slow the viewer down and make them relook at painting."

Flowers caused a stir – one viewer demanded to view the entire three-hour cycle – and it will become the first digital work to go on display at New York's Frick Collection from next month. "A framed iMac alongside Girl with a Pearl Earring speaks volumes for the way galleries and collectors are embracing rapid change," says Rob.

They followed it with Transforming Vanitas Painting, based on Dead Frog with Flies by Ambrosius Bosschaert the Younger, and in it they animate an amphibian's life as it decomposes. The three-hour piece is so visceral that it prompted Sooke, who compared it to Damien Hirst's work, to decide he wants to be cremated when he dies.

The critic said: "In order to be successful as works of art, the Transforming films must be about more than the technology that was required to produce them – and I believe they are."

In 15 years of working together, Rob and Nick Carter have blurred the boundaries between painting, sculpture, instillation work and digital imagery. They met at school at the age of 16, but did not collaborate until they became a couple 10 years later. Rob specialised in fine art photography and Nick in painting.

Their early, vibrant pieces are often displayed in corporate settings where large-scale, eye-catching art is de rigueur. The new work is quieter, but with just as much impact.

This week's exhibition will also include their pixellated paintings, the Chinese Whispers series – in which workshops in China copy an Andy Warhol image, which becomes increasingly distorted – and their Composite Portraits series.

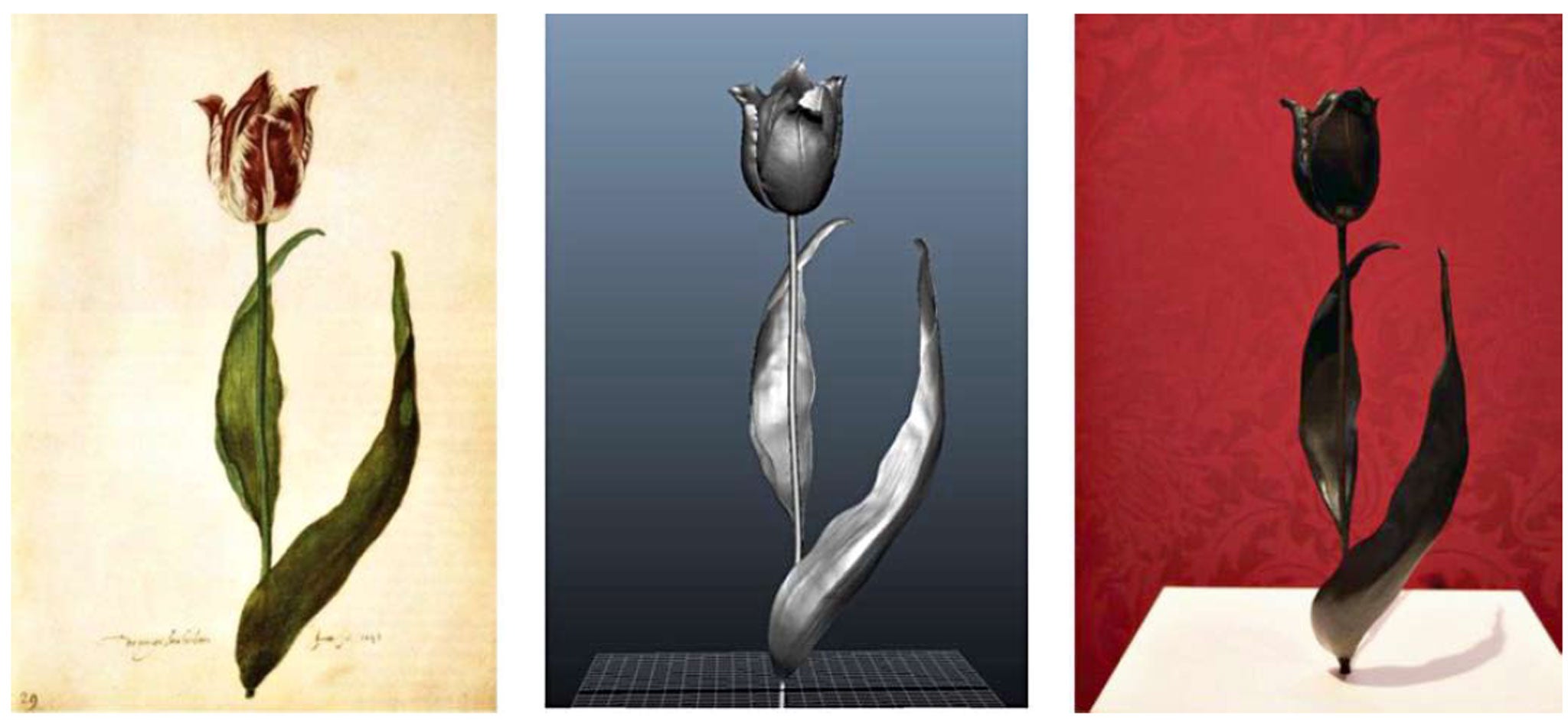

It will also include a 3D sculpture of possibly the most famous still-life painting ever: Van Gogh's Sunflowers, which they have turned into a bronze sculpture, complete with Van Gogh's signature and brushstrokes.

Rob and Nick Carter: Transforming from 4th October - 2 November 2013 at The Fine Art Society Contemporary.

How we clicked with digital art

This month the John Lewis department store publicised the latest state-of-the-art televisions by hanging them in a gallery and using the screens to display crystal-clear digital art. If it may be a little while before average punters follow its lead, collectors, dealers and gallerists are paying increasing attention to digital art.

Sue Gollifer, principal lecturer in fine art at the University of Brighton, said: "I would like to think that digital art is now a fully accepted art form in its own right." Ms Gollifer, who runs an MA in digital media arts, added: "As computers become more mainstream and accessible, people will be collecting digital art in all its many transformations and iterations in the same way as traditional art."

It emerged in the 1960s, with generative software-based work. Artists wrote their own code and created drawings printed out from punch cards. Among the early pioneers was John Whitney senior, dubbed the "father of computer graphics", who used old military equipment for his work and became IBM's first artist-in-residence.

Cybernetic Serendipity, an exhibition at the ICA in London curated by Jasia Reichardt, was a landmark show in 1968.

An increase in the use of personal computers in the 1980s followed by the advent of the worldwide web in the 1990s helped drive the rise of artists using a digital medium, according to Christiane Paul, who wrote Digital Art.

Ms Paul said: "You see it more and more, but museums and the art market are still struggling with accommodating it because it presents so many challenges in its presentation, collection and preservation."

Exhibitions focusing on digital art have become more common and the V&A has been collecting computer art since the 1960s, the museum's digital curator, Louise Shannon, said. "More private collectors are taking the leap and commercial galleries are representing artists who feature digital practice," she added.

And for those who don't live in vast, gallery-like modern homes, digital art can be highly desirable, both in terms of cost and ease of display.

Nick Clark and Rakesh Ramchurn

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments