Voytek: Designer who carried out bold and innovative film, theatre and television work, making a virtue of often tight budgets

he key to his success as a designer, besides his powerful imagination, was his dedication to a script

The French windows were flung open on the British stage in the 1950s, with designers such as Voytek and the Royal Court's Jocelyn Herbert bringing a touch of Brecht to new work by writers from Beckett to Osborne. Voytek's work was often a victory against seemingly insurmountable odds of space or budget, in the theatre and on television, where he used space and light to bring the actors forward in what were often stark settings where there was nowhere for weak writing to hide.

The key to his success as a designer, besides his powerful imagination, was his dedication to a script. He read a play carefully, repeatedly, trying to identify its mood as much as the geography.

The son of a doctor, Voytek (his trade name was coined for him by the director George Devine, who, like everybody else, struggled with Wojciech Roman Pawel Jerzy Szendzikowski), was born and raised in Warsaw. During the German occupation the operation to destroy Polish culture led to the forming of an underground university which he attended to study architecture. But he left at 19 to join the resistance as part of the 1944 Warsaw uprising, at one point taking a bullet in the shoulder.

He ran the wrong way during a battle and found himself taking on 40 German soldiers, for which he won the Polish Military Cross. He was later captured, and when liberated walked to Italy, where he joined the exiled Polish Army. After the war he studied design at Dundee Arts College and then at the Old Vic.

He made masks and costumes for the Arts Theatre, designed the odd restaurant and then spent three and a half years as the resident designer at Nottingham Playhouse, where his work was remarked upon for its boldness and its ability to suggest a wider sweep than was possible on such a small stage. Foreshadowing his later parlour tricks in the use of light on a set, a Juliet approached death bathed in a white light which was said to evoke "the very clamminess of the grave".

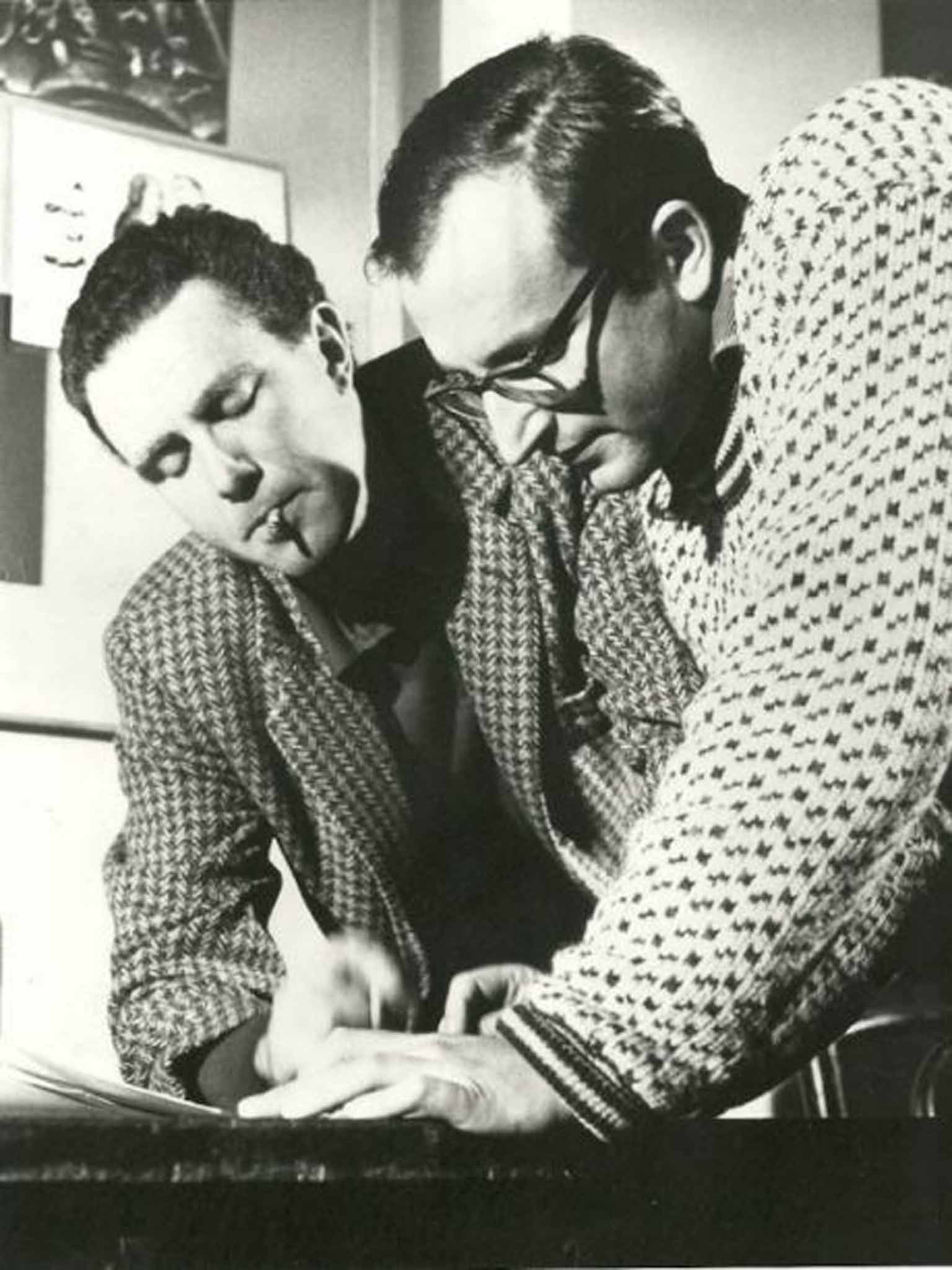

In 1958 he moved into television, joining ABC, and spent seven years designing for Armchair Theatre, often working with pioneering directors Philip Saville and Ted Kotcheff. The Pilkington Report into Broadcasting in 1962 commended the company for their belief that "those who claim they know what the public want rarely do but always underestimate".

Voytek would have 26 days from being briefed to the transmission of an Armchair Theatre. In that time he had to give 14 days' notice to the construction department, and in the odd emergency even designed a play in a day. Watching television could be a foggy experience in the early 1960s, so he made his backgrounds vivid "to prevent them being washed out by the time they reached the viewer". He won a Guild of Television Producers and Directors Award in 1961 for his work on the series.

Notable works for the strand included "No Trams to Lime Street" (1961), "Three on a Gasring" (1959), which was banned for featuring a pregnant teenager showing no remorse, and Charles Wood's "Prisoner and Escort" (1964), which made a staggering virtue of its lowly budget by eschewing construction of a realistic set. Voytek created a performance space rather than a narrative space, with prop men visibly sliding sets in and out, and with rigs and scaffold surrounding the action. The metafictional style was all part of the boundless creativity that thrived in the early days of this strange new medium and which was often born out of the need to somehow achieve the impossible on very limited resources.

Contrast magazine called "The Rose Affair" (1961) "the most discussed drama of the year". A stylised reimagining of Beauty and the Beast with masked actors (Voytek again used masks to great effect in a 1984 Merchant of Venice for the Shared Experience Theatre Company), it served as a good reminder of the sheer diversity of the strand that short-sighted Conservative critics called "Armpit Theatre".

He spent eight years as a television director on excellent series such as Callan and Man at the Top; mention should also be made of a "Frankenstein" starring Ian Holm for Mystery and Imagination (1968) and, on a return to Armchair Theatre, Fay Weldon's "The Office Party" (1971), a slight but well-observed study of cultural change through the conceit of the retirement of an old-fashioned bank manager.

His work for the RSC included creating a globular conservatory for Ronald Eyre's Much Ado About Nothing (1971), and again with his love of creating self-contained structures for the drama to play within, he won a Critics Circle Award in 1983 for Great and Small at the Vaudeville, which was set inside a plastic cage. On a return to television for Mike Hodges he set Stoppard's Squaring the Circle (1984) inside a set that visibly reconstructed itself between acts. It was again an effective injection of Brechtian theatricality into what was by then an almost entirely naturalist and largely mundane medium.

His film work was occasional but in the case of Polanski's Cul-de-Sac (1966) well up to the standard of the two more intimate mediums he favoured. He bowed out of television winning a Bafta for his work on the thriller Dandelion Dead (1994). It was a final endorsement of a constantly courageous and sensitive talent that was vital in realising the revolution that occurred first in theatre and then in television, as much visual as it was ideological.

Wojciech Roman Pawel Jerzy Szendzikowski (Voytek), designer, director, producer, and writer: born Warsaw 15 January 1925; married firstly Renee Bergmann (marriage dissolved; two daughters, one son), secondly Fionnuala Kenny (marriage dissolved; one daughter); died London 7 August 2014.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies