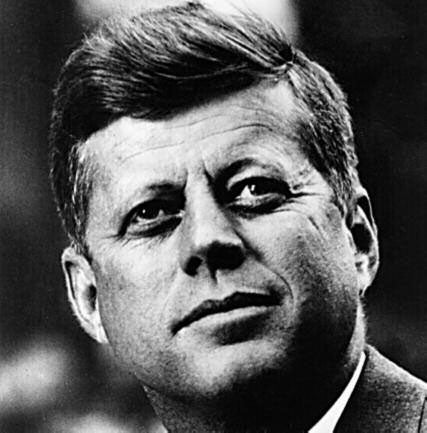

John F Kennedy: The grand illusionist

35th president - 1961-1963

In strange symmetry with his enemy Che Guevara, John F Kennedy became an icon, with film attached. He was – at least as we look on these things: earlier generations preferred maturity – the handsomest president ever, and, like Che, he had a tragic, mysterious fate. When he was assassinated in 1963, the date – 22 November – became one of the very few that have sunk into the mass memory. ("Where were you when Kennedy was killed?") The funeral was a very solemn and tragic affair, as the widow, herself a strikingly good-looking woman, veiled in black, held her three-year-old boy's hand as they walked, with his slightly older sister, towards the funeral service in the Cathedral. The little boy touched the world as he saluted his father's coffin. It is, again, an image that has never quite left the world's retina. Kennedy became a symbol, and it is interesting that his daughter Caroline has endorsed President Obama, who already has a whiff of Kennedy about him. But what, in substance, did Kennedy leave?

The great presidents bequeathed concrete achievements that can still be argued about: Roosevelt's New Deal of the Thirties being the most obvious case. Back then, with 25 million unemployed, the USA acquired a social-security framework; the federal government overrode separate states and even the Constitution to set it up. For a generation, Roosevelt then counted as a hero. But – as also happened with the Labour government of 1945 in Britain – the experience of the later Seventies caused some questioning of the welfare-state ("Keynesian") formula; with "stagflation", unemployment and inflation together with economic paralysis and a widening mistrust of government. In the USA, the Roosevelt legacy was challenged, and the Republican Right came to dominate affairs.

Oddly enough, Kennedy's one substantial legacy proved useful to them. He had proposed a cut (passed after his death) in the top rate of tax, from 91 to 70 per cent. By 1965, said the Right, that cut meant the rich did not avoid tax and instead worked more productively: revenue rose. As Reagan told a press conference in October 1981, Kennedy had gone ahead despite advice "that he couldn't do that. But he cut those taxes, and the Government ended up getting more revenues because of the almost instant stimula ( sic) to the economy." The Keynesians said no, no, it was not like that, and the episode is now forgotten. But that is the one concrete Kennedy legacy.

However, there was a huge discrepancy between the whole and the very modest sum of the parts. This was a presidency full of glamour and movement: crisis after crisis (the worst in October 1962 when the world came close to nuclear war) but also Vladimir Horowitz in the White House, and a birthday party in Madison Square, at which Marilyn Monroe, probably a Kennedy girlfriend, sang. In terms of image, there has never been a more interesting presidency and, as the Obama start shows, it was one that continues to inspire. It is of course true that, with Kennedy dead, the hostile biographies got under way.

He had a mistress or two (or three), and that marriage was not the chocolate-box picture of legend. (Jacqueline, after his death, quite soon made a Beauty-and-the-Beast marriage with Aristotle Onassis.) Kennedy got away with things that nearly brought down Clinton, because the media liked him. We can pass over this aspect. Paragons of the minor virtues have not always made very good Presidents: the uxorious Ford, for instance, and still poorer Jimmy Carter, doggedly holding his scrawny sexagenarian wife's hand on this or that ineptly-managed international occasion. How does the Kennedy record hold up?

Chateaubriand remarked of Talleyrand that he was a 19th-century parvenu's idea of an 18th-century grand seigneur, and there was in Kennedy an element of the hairdresser's Harvard. The style was rich Boston: silver spoons all round, Ivy League voice and confidence, yachting, grand connections abroad (one sister-in-law was a Cavendish, another a Radziwill). The reality was not quite what it seemed to be. The background was indeed Boston, but the ancestral boats had arrived two and a half centuries too late. Kennedy was not of ancient Puritan descent: quite the contrary, he was from a Catholic, Irish background, the grandfathers and cousins being Murphys, Hannans, Hickeys, Fitzgeralds. There was tension between the Boston Irish and the local ascendancy of Cabot Lodges and Lowells and Winthrops, but, America being America, within a generation or two the Irish immigrants had shot up the ladder. John F's grandfather, "Honey" Fitzgerald, became mayor of Boston. Kennedy senior, Joseph P, went to Harvard and made a great deal of money – some said, by bootlegging liquor during the years of Prohibition, but he was overall a Midas, everything turning into gold. Roosevelt made him ambassador to London, where he made a bad name for himself (of which more in a moment).

John F Kennedy himself was born in 1917, the second son. The only black spot in an otherwise standard-issue rich Thirties boy existence was a childhood illness, the consequences of which never quite left him (he had a bad back all his life, and put up with it heroically). He had a good war in the Navy. At his father's behest, in 1946, on the Irish Democrat circuit, he went into politics, as a Congressman. There followed a suitable match, to the also rich and beautiful Jacqueline Bouvier, in 1953 and a seat in the Senate (won in 1952 from Henry Cabot Lodge, a sign that the Protestant Boston-Brahmin ascendancy was over). So far, so standard for the United States, and there remains an interesting question, as to why the Irish in America at that time flourished so much more than the Irish in England.

Over this period in Kennedy's life, there is indeed some legitimate muck-raking to be done. Later on, he became the great white hope of American liberals – associated with all of the right causes. That was not how it seemed at the time. Kennedy's father was a grasping monster. He had made himself very helpful to Roosevelt, lining up the Irish vote, and Roosevelt rewarded him (or got him out of the way) by naming him ambassador to the Court of St James in the later Thirties. He was in London during the Blitz, and distinguished himself by cowardice and defeatism; he even managed to say in public that the British were not fighting for democracy, and he also did not disguise his anti-semitism. He was in effect sacked, and relapsed thereafter into querulous political inactivity, but wanted to keep a presence just the same. His oldest son had been killed in the War (the first in an extraordinary set of family disasters, almost as if the gods had settled on a generations-long retribution). Old Joseph decided that he wanted a son in politics, pushed John F ("Jack") and set about greasing the right palms. One of these belonged to Senator Joe McCarthy, then (c1950) making a name for himself as Grand Inquisitor of un-American Activities. Hollywood and even the State Department had its crypto-Communists, and a witch-hunt ensued (to which even Charlie Chaplin and Graham Greene fell victim). Young Kennedy went along with McCarthy, and his brother, Robert, served on his staff: the deal was that John F would not denounce McCarthy in Boston, and thus got McCarthyite support. (It should be said that Ronald Reagan, as leader of the actors' union at the time, behaved far more scrupulously than Kennedy did). At any rate, the Catholic constituency was secure, Kennedy won a seat in the Senate, in 1956 put himself forward as presidential candidate for the Democratic Party, and in 1960 won the nomination.

The Democratic Party was a strange amalgam, a strong element in it being Southern, Baptist and – at the time – very keen to preserve States' rights so that it could go on with white supremacy. The Southern vote was secured because Kennedy found the ideal fixer in his future vice-president, Lyndon Johnson, who had earlier fixed Congress for Roosevelt and who, as a Texan, was in a very good position to fix much else. The third element, relatively new to politics, was Jewish. The American Jews had, by and large, voted for Kennedy. In 1960, he told Ben Gurion that he had been elected "by the Jews" and wondered what he could do in return. Ben Gurion much preferred the support he had had from Europe – the French gave Israel arms – and especially from the Left; he did not want to be treated as "some Jewish Mayor Daley" (in Geoffrey Wheatcroft's words). The State Department had not been enthusiastic about Israel, had criticised her, and had pressed for some solution to the refugee problem. Now, matters began to change, as Hawk missiles were sold. You can, if you like, see something sinister in this, the rise of the Jewish Lobby, of which there is much talk, the more so as some of the then Kennedy supporters have turned into today's "neo-cons". But there were more important factors in bringing change to the State Department position. It supported Nasser in consort with Moscow and interfered murderously elsewhere (Eisenhower confessed later that his greatest mistake had been to fail to support the British and French over Suez). Iraq had had a foul revolution, and the murderous destabilisation of the Lebanese haven had begun. Israel, in this perspective, became a useful ally. Kennedy himself dismissed any idea of enforcing a return of the Palestinian refugees from the Gaza Strip: "It's like a Negro wanting to go back to Mississippi, isn't it". Not the most sensitive of remarks, but was the gist wrong?

The Democratic amalgam made for a Kennedy victory in the election of 1960, and his opponent was Richard Nixon. The main instrument now coming up in politics was television: 14 million television sets, which senior politicians did not know how to exploit. There was a debate. Nixon's eyes did not focus properly, and he looked unshaven; he would not use make-up; he came across as a stage villain. Not John F Kennedy: the friendly (made-up) face, the gleaming teeth, the air of youth. Nixon somehow made himself hated in media circles, in the end his downfall, and though people who heard the debate on the radio reckoned that he had won, the television spectators were overwhelmingly on Kennedy's side. Nixon came across as cross-examination-lawyerly, whereas Kennedy charmed: "Do you realise the responsibility I carry? I'm the only person standing between Nixon and the White House." He squeaked into victory. Kennedy won by a tiny majority – 49.7 per cent to 49.5 per cent – and there were suspicions that voting in Illinois (Mayor Daley's Chicago) had been fixed. So, too, had votes in Texas, and here the fixer was Lyndon Johnson, a one-time Roosevelt congressional manager, but he had the grace to concede, and "the New Frontier" was the theme of Kennedy's Inaugural, in January 1961. Joseph Kennedy had remarked, "image is reality", and that was the underlying theme. If politicians use the word "new", beware: they are salesmen.

Besides, whatever the deals he had had to make with the Boston Democrats (or for that matter their southern allies) he at least had promise, in the eyes of east-coast liberals, of turning into something different. When, at the Democratic convention of 1960, he made a speech indicating a "New Frontier", this seemed to mean something. The backdrop was rule by elderly Republicans, especially President Dwight D Eisenhower, genial, golf-playing, and allegedly incapable of getting grammar right; there was apple-cheeked Mamie, offering tea and cookies, and much of the east coast snorted with contempt. Norman Mailer called the Fifties the worst decade in the history of mankind. The USA in this view were simply not using their enormous weight to proper effect. Health was a disaster; the cities were dreadfully badly managed; the race matter was a national disgrace. Under the federal system, separate States could become stagnant, even malignant backwaters. This was most obvious in the case of the southern States and their preposterous White supremacy, but it even affected Kennedy's own backyard. The Catholic control meant that contraceptives were unavailable, and it was local Republican ladies of great respectability who fought that matter through the legal system. (They won, but only after a 15-year battle, and it resulted in the decision, in 1973, to allow not just contraception but abortion on easy terms.)

As seems to happen in American publishing, there was one of those 20-year moments when a small spate of books appears, all with variations on a theme. Looking back, it is not easy to understand quite why such heat was generated; Fifties America had seen an extraordinary miracle of progress, gadgets all around, businesses such as IBM working wonders; as late as 1970, American workers had twice the purchasing power of German ones. But in 1960 there was a widespread notion that the USA were not managing what they should be managing: time for a new New Deal. This coincided with a two-year slow-down in the economy, when it grew by 2 per cent and unemployment came close to 6 per cent, then thought excessive. These questions gave Kennedy his narrow margin at the end of 1960, and when he took over, early in 1961, "New Frontier" was the watchword.

Ambitious academics advised as to how the challenge was to be met. There were some famous and influential books, and conservatism had a bad time. These new writers analysed problems, and often suggested easy-sounding solutions – one mark of the Sixties. John Kenneth Galbraith's The Affluent Society (1957) noted that private people had money and governments none the less produced squalor: New York gorged with money, yet the roads were potholed and a good part of the population lived in poor conditions. Two decades later governments had a great deal more money and were still producing squalor: what conclusion was to be drawn? That governments should have even more? Or that they just could not help producing squalor? Vance Packard's Status Seekers (1960) described the American business rat-race. Jane Jacobs, looking at the wreckage caused by the San Francisco freeway-system, wrote The Life and Death of Great American Cities (1961) and foresaw that housing estates for the poor would turn into sinks of hopelessness worse than the slums that they were to replace; she also foresaw that city centres would become empty, inhabited only by tramps. Betty Friedan's The Feminine Mystique (1963) spoke for the bored housewife. Michael Harington discovered that there were many poor Americans: The Other America (1962). David Rieff looked at the wider American rat-race ( The Lonely Crowd) and shook his head at the two-dimensional misery of it all. René Dumont considered international aid, and thought that there should be much more of it; Gunnar Myrdal saw American race-relations in the same light.

Some of this was superficial, but there was at bottom, just the same, an immense and growing problem: race. What had happened with the American Negro – the then polite word – was indeed a disgrace. Kennedy's own vice-president complained that, when he drove in Texas, his negro cook, unable to use public lavatories, squatted by the side of the road. Two small boys, aged seven and nine, kissed a white girl in the playground and were put in prison for years. If you took a negro friend to a restaurant in New York, you telephoned the management beforehand to find out if there was a problem. Race was the central and by far the greatest question in American life, poisoning everything around. It destroyed the old Democratic party. That had been a strange coalition, of Southern Whites standing on states' rights – the "Dixiecrats" – and Catholic machine-politicians, with an element of liberal-minded Protestants, of which Roosevelt had been (in his way) an exemplar. Kennedy had to go very carefully if he was not to shatter this unlikely combination. As President, he allowed the telephone of Martin Luther King himself to be bugged, and Supreme Court appointments went the Southerners' way. In fact, Eisenhower had a better record, as regards both McCarthy and race, than did Kennedy– it was he who enforced school and bus de-segregation (and he also, at the very end, who denounced the "military-industrial complex" for its role in the nuclear arms competition with the Soviet Union).

In fact, Kennedy denounced the Eisenhower regime for letting the USSR overtake America as regards nuclear missiles. Hereby hung a tale or two. The 40th anniversary of the Revolution in 1957 had been triumphalist, with huge thermonuclear tests in the offing, and the fall of the Winter Palace was celebrated by an extraordinary symbol: Sputnik, the first man-made satellite in space. That little spot of light, going round the Earth and making its "bleep", seemed to indicate that the Soviet Union was winning, that Planning under Communism was the way of the future, not disorganised American capitalism. The 80kg Sputnik seemed to shame the Americans: their kitchen gadgets were no doubt splendid, but they failed lamentably to put even a football-sized satellite into space. Khrushchev beamed: "It is the United States which is now intent on catching up." A 21st Congress of the Communist Party in January 1959 announced that the USSR itself would "catch up" by 1970 and a further one in October 1961 was more precise: five years to catch up, and even, by 1980, "super-abundance".

This was all bogus or utterly misleading. The Americans had not put an effort into ballistic missiles because they concentrated on military aircraft to deliver bombs (and, through the needs of defence, also promoted computers). Besides, Sputnik itself was not what it seemed. In the first place, the equations that shot Sputnik into orbit had been devised by Konstantin Tsiolkovsky in 1903 – the "achievements" of the Soviet Union generally reflected the old Tsarist-Russian educational system, especially in mathematics, rather than Communism, under which many of the best scientists had been murdered or imprisoned (including Korolev, the chief designer of Sputnik).

Then again, some of the engineering came from captured German rocket scientists, the makers of the V2 that had terrorised London in 1944 and 1945. It was only really Hitler and then the Cold War that caused Moscow's rulers to behave sensibly, and one of the Soviet scientists was eavesdropped by the KGB as saying that the first lives to be saved by nuclear deterrence were those of the Soviet scientists. But in 1960, the Americans were never the less spurred into a great effort to catch up.

No one would speak up for Soviet Planning now. But that was not how, in 1960, it looked, and when Kennedy spoke for his New Frontier, the vision he conveyed was of men in white coats offering Progress. Around him, he collected a team of "the best and the brightest", as the title of David Halberstam's famous book (of 1973) ran. (There were no women, as yet, but here again Kennedy struck the tuning-fork for the swelling anthem to come; he set up a commission "on the status of women" in 1961.) McGeorge Bundy (from an old Boston family), Robert McNamara from the Harvard Business School, and Walt Rostow, from MIT – each one of them was versatile and from the very top of academe. Harvard had an enlightened system, by which such brains were supposed (as, at the time, with Research Fellowships at Oxford and Cambridge) not to have to bother with the drudgery of a PhD thesis, a chore for lesser talents ("Mr" was the honourable title), and Bundy was not only firmly "Mr", but the youngest Harvard Dean in history. Rostow was an extremely interesting man who wrote a characteristic book of the age (now seeming rather naive): Stages of Economic Growth. It identified a moment of industrial take-off, when countries saved enough of their GDP to foster investment and thence an industrial revolution, and development economics went ahead, with an assumption that squeezing peasants would mean investment for big industry. Latin America seemed ripe for treatment of this sort.

New Frontier was the theme of Kennedy's inaugural, in January 1961. A Peace Corps was established, as an alternative to the conscription-draft, by which young Americans were sent all over the globe to help with this or that worthy project. This did good: the present-day professor of Turkish studies at Princeton, Heath Lowry, son of a missionary in India, says that he just opened the Peace Corps booklet at random, hit upon the letter "T", and found himself in an Anatolian village, the rest being (rather good) history. On the same level, Kennedy also promoted "arts in a vital society" – a National Endowment was to follow (after his death). In terms of squaring liberals, so far so good, and John Kenneth Galbraith craggily beamed. The American intelligentsia had often felt rather inferior when it came to Europe: as Michael Ledeen, representing the CIA in Italy, remarked, the wines, the women, the films were overwhelming. Now, America could compete. No more would a Harold Nicolson do the coast-to-coast lecture circuit, be received in one Peoria after another by ladies in cherried hats offering cookies, announce that the two democracies were standing shoulder to shoulder facing the foe to the east, and then return to London saying that it had been "like a month at a servants' ball".

Still, be it not forgotten that the USA in the Sixties ran into disaster. There was Vietnam. There was (and is) the absurd stand-off with Cuba. Race-relations turned very sour indeed, and a sort of civil war opened up. Finally, there was the end, in 1971, of the fixed-rate international exchanges, collectively known as "Bretton Woods", that had caused an enormous boom in world trade, and given the western world that period of extraordinary prosperity that the French know as the trente glorieuses. With each and every one, at least the little finger points at John F Kennedy. Did anything that he touched really turn out right? As regards Bretton Woods, the dollar could not be the underpinning of the world's trade if the Americans did not follow the rules. In 1960, there were already more dollars held in Europe than there was gold in Fort Knox to honour the paper, if presented. Kennedy, Galbraith beaming, took the first step into a world of deficits, and thence of inflation, that was to bring Bretton Woods down a decade later, and cause oil prices, in dollars, to multiply by four and then by eight.

Kennedy mis-managed the first crisis, over Cuba. That island made for legend – Che agonizing all over T-shirts – and you could easily run up a Marxist account, of down-trodden peons, rapacious landlords, a "comprador" class of foreign-origin middlemen who did the American trade, plus revolutionary intelligentsia, etc. The Americans used Cuba often enough as an escape from tea and cookies, but the place was better off than almost anywhere else in Latin America, whatever the grubbiness of its banana-republic politicos. The Americans are bad at imperialism, producing naive, conscience-struck State Departmentery at one level and mafia crooks on another. Self-disgust struck some of them, and a New York Times journalist gave encouragement to Fidel Castro, quite misleading him (an admirer of Mussolini, who, as a Russian minder complained, only thought in terms of headlines) into thinking he was a sort of Robin Hood.

The Americans pushed out the grubby dictator, and in January 1959 Castro took over, soon organising public executions and nationalising American business. Early in 1960, Moscow took an interest, the progressives arrived beardedly from abroad, and Le Corbusier with glee designed a prison. There was also a small flood of refugees, at 2,000 per day on occasion. The CIA wanted to overthrow Castro, and had a plan, of a sort. Preparations went ahead for a landing at the Bay of Pigs; but in Guatemala, where a hundred different Cuban exile-groups were represented, there was an atmosphere of black farce: a brothel was built for them, while the American trainers, arrogant and speaking no Spanish, lived apart and better, while their commander, a colonel, simply said, "I just don't trust any goddam Cuban." A farce followed in 1961, the invasion-force rounded up (and ransomed) as its boats crashed into reefs and its walkie-talkies were swamped in deep water. Kennedy had sanctioned this, but had – characteristically – shrunk from using the air-power that might have made a difference. Would a more understanding President have made some sort of terms with Castro? No one really knows.

At any rate, Cuba then became, as Lawrence said of Balzac, a sort of gigantic dwarf. The initial crisis led to a nuclear confrontation in October 1962 – the moment for which Kennedy will always be remembered. The Russians planted missiles in Cuba, lied about it, were found out. Kennedy decided to impose a blockade, to stop further Soviet missiles from arriving, and a few days' stalemate followed, with alarms on both sides, until finally a deal was done: no Russian rockets on Cuba, American rockets to be withdrawn from Turkey. Kennedy was much-praised for his firmness on this occasion, as also for his willingness to find a way out. How does this record now look?

The Cuban Crisis needs to be looked at in the Cold War context. The central problem was, as it always had been since 1948, Berlin. Here was an American island – a somewhat artificially prosperous island – in the very middle of Communist East Germany. Post-war agreements meant that there was an open border between East and West Berlin; as West Germany prospered in the trente glorieuses, East Germans walked or took the subway to the West. By 1960, they were doing so at the rate of 2,000 per day. If this went on, East Germany would implode (as was to happen in 1989). How was Moscow to deal with the problem? Stalin had tried force, a blockade, and had been thwarted when the Allies just flew in supplies to keep West Berlin going. Khrushchev tried another method, detente. To Eisenhower, he talked disarmament, and bought American grain. To the Germans, he allowed talk of an Austrian solution – neutrality and unification. De Gaulle in France was only too willing to listen to anyone willing to recognise his country's great-power role, and Harold Macmillan came, on a not very successful visit. Khrushchev and Gromyko easily understood that no one in the West really wanted to fight for West Berlin: let them quarrel among themselves.

As a French expert. Georges-Henri Soutou, says, they were all fighting the Cold War, but they were each fightingtheir own Cold War. At Geneva, when there was a conference on the subject, that squabbling duly occurred, Germans mistrusting Americans, Americans mistrusting British, and everyone mistrusting the French. Khrushchev rubbed his fat little hands in glee, and served an ultimatum. He would recognise East Germany, including Berlin as its capital, and the Allies would then have to deal with the East Germans when it came to access over Berlin, not the Russians, whose hands were bound by war-time agreements. Meanwhile, he was taking tricks in the Middle East, and emissaries from all over the world were turning up as supplicants on his Kremlin doorstep – the Shah of Iran, the inevitable Chinese. This went to his head. He humiliated Eisenhower at a Paris conference, banged his shoe on the desk at the United Nations, and graciously agreed to wait and see what the West would offer him over Berlin.

In June 1961, John F Kennedy offered to meet him, in Vienna, to talk things over, and the meeting was not a success – or, rather, Khrushchev looked contemptuously upon this "boy", with his well-meaning platitudes, and thought that he could easily get the better of him.

Kennedy had made the mistake of sending Walt Rostow to Moscow to explain that he had an interest in disarmament – not a matter likely to please his Allies. America had been losing in Cuba and elsewhere. There had also been a widespread notion, since Sputnik, that western capitalism was just too disorganised and self-indulgent to "win", that Cuban revolutions would happen all over the place, at Soviet behest. Khrushchev, for his part, was ebullient. Here was this crude, tubby little man, who owed such education as he had had to a priest, who had taught him the rudiments in exchange for potatoes. The Russian Revolution had swept him to the top. He patronised Kennedy, and wrote him off. As the Berlin haemorrhage went ahead, he sanctioned the building of a wall to keep the people in their cage. On 13 August 1961, up it went, the ugliest symbol (with severe competition) of Communism. The Americans did nothing.

More than a year later, Kennedy went to see the Wall, in the course of a visit designed to propitiate the alarmed Germans. In the course of a speech he said, famously, " Ich bin ein Berliner", which was not grammatical (the " ein" is redundant, and a Berliner is a sort of doughnut) though everyone knew what he meant. But even there he was misleading his audience: the Americans would not have the Wall pulled down. It suited them well enough to have that demarcation line where it was, and in March 1962 they made this plain enough, when they sent proposals over disarmament that amounted to a Soviet-American condominium in Europe. But Khrushchev was after bigger game. He was now megalomaniacally full of himself, having at last made East Germany a stable place, and fancying that he could at last secure the bullied, neutral Germany that had been a Soviet objective all along. He exploded a monstrous 50-megaton bomb on 30 October, expected to browbeat West Germany into neutrality, and at the same time he would show the adolescent Kennedy who was the master. He would also silence colleagues on the Politburo who hated his denunciations of Stalin and his boat-rocking reforms of the Party. He would place missiles on Cuba, a few dozen miles from Florida.

Cuba, the locus classicus of Third-World revolt, offered a good stage. In 1962, by stealth, Soviet missiles were gradually installed there, Castro being told that this was cover against a new American invasion attempt. Castro himself, another megalomaniac, preened: recognition at last. To Cuba, the Russians sent much more than was originally thought – 50,000 men, not 10,000, and 85 ships, and there were 80 nuclear weapons of differing range. On 14 October an American spy plane showed that missile bases were being constructed. Khrushchev wanted the secret kept so that Kennedy would not be forced into a public confrontation, but he meant, when he went to the UN in New York in November, to make a grand public announcement.

This was completely to misunderstand Kennedy, the more so as there was an election in the offing, and the Republicans made a great fuss about the arrival of Soviet troops (at which Khrushchev ordered yet more, tactical, missiles to be dispatched). On 18 October, Washington realised that the problem was even more serious than had been thought, and when, that evening, Gromyko called, and straight-forwardly lied in denying the presence of missiles, Kennedy announced (on 20 October) that there would be a blockade of Cuba, that Soviet ships would be stopped. Soviet forces were put on alert, and Khrushchev sent a message that he would not respect the blockade, but American forces were also put on alert (24 October) with many nuclear-armed bombers permanently in the air. Would the USSR try and force the blockade? 25 and 26 October marked the height of the crisis. Khrushchev realised that Kennedy was entirely serious, that he would invade Cuba, and was not bluffing. A letter was then composed. The Soviet missiles would be withdrawn, in return for an American pledge not to invade Cuba; after some more nail-biting, a further and secret condition was attached, that the Americans would withdraw their own missiles from Turkey. On 28 October, an agreement was announced, and a hotline telephone was installed on the desks of Kennedy and Khrushchev, with a view to avoidance of such problems ever again. Castro was enraged (he broke a mirror) but had the last laugh, when Khrushchev was overthrown by colleagues terrified of his antics. But would he have indulged in them but for the initial clumsiness of Kennedy's approach to him? An open question.

At any rate, the rivalry with Khrushchev prompted Kennedy into a final and fatal step: Vietnam. We can recognise the Vietnam war as one of modern America's great disasters, and Kennedy bears some responsibility for it. America in the Far East had done remarkably well: Japan and Taiwan were considerable success stories, but before then there had been a successful pacification of the Philippines. Vietnam, a French colony, did not seem much different: some American money, a few military advisers, a bit of help as regards "state building", and all would be well. All was not well. A "peasant war" developed, as Communist guerrilleros came in from the North and infiltrated villages that contained peasants discontented with bullying officials and grasping middlemen. The South was run by a clique of Catholics, who had stepped into the shoes of the French, and the complications of the place went on and on (and on). De Gaulle advised against involvement – un pays foutu, he said. But it was Kennedy again who took the wrong turning. Almost unthinkingly, he continued an earlier policy, itself none-too-well thought through.

"Advisers" – some 800 – were already present, and Kennedy put up the numbers, to 16,000; under him, too, came plans for free-fire zones, the use of napalm and defoliants to defeat guerrilleros hiding in the jungle. Under his successor, these things blackened America's reputation. But Kennedy did more: this complicated country could only really be managed by a suitable, if surreal, regime, and Kennedy did not understand that the insufferable Ngo Dinh Diem, by turns stuffy and monomanical, was the only answer. In July 1963, he authorised the overthrow of Ngo Dinh Diem, who was in the event murdered. South Vietnamese politics then went into a tailspin, and when Kennedy himself was assassinated a few weeks later, his wife received a very barbed letter of condolence from Madame Nhu, Diem's sister-in-law.

For John F Kennedy himself was murdered. It was a most extraordinary murder, in its way a descant upon the American dream, in the sense that a "loner", Lee Harvey Oswald, product of a (very) broken home, failed volunteer for the military and the CIA and the KGB, acquired a gun, thanks to America's lawlessness in that regard (he got it by mail order), and, his brain full of confusion, thought of murder. Kennedy rode in an open car through Dallas, Texas. Oswald fired, and killed. He was then himself caught, and was shot by a man with mafia connections who himself was dying of cancer. There is easily stuff here for an Oliver Stone film, and you can understand why so many people could not believe that such a surreal set of events could have been genuine. The same was said about the Reichstag fire of 1933: that such a huge and (for the Nazis) convenient blaze could not have been started by one man alone. But it was, and conspiracy theories have never stood up. Kennedy at least ensured, with his death, that he entered American legend.

All of the neon enlightenment of the Kennedy moment cast a terrible shadow. In 1961, old Joseph himself had a stroke, which prevented him from speaking and had him in a wheelchair: but he went on and on, not dying for another 20 years, and fully conscious of what was happening. A daughter with depression had a lobotomy that went wrong and made her a vegetable (she too lived on and on). His oldest son had been killed in the War, two others were murdered, and another daughter, Marchioness of Hartington, was killed in a plane crash with her lover, Earl Fitzwilliam. The last son, Edward Kennedy, has been lucky to avoid a charge of manslaughter, while two of Robert Kennedy's sons died tragically young, one from a cocaine overdose and another in a skiing accident. John F Kennedy's own son, the poor little boy of 1963, was killed while flying an aircraft. Lesser disasters pass unnoticed in this terrible catalogue, which is relieved only by the common-sense daughter, Caroline who has made a solid and independent career for herself.

The death of Kennedy brought the greatest outpouring of breast-beating grief that the world had seen until the death of Diana, Princess of Wales a quarter-century later. A Guardian man said that: "For the first time in my life I think I know how the disciples felt when Jesus was crucified." Terrible doggerel verse from Robert Lowell; sentimental nonsense from Arthur Schlesinger; a preposterous exercise in pre-"Hitler Diary" absurdity from a Hugh Trevor-Roper, apparently convinced that the murder was a conspiracy. Malcolm Muggeridge, as ever, spoke for common sense with an inspired essay which The New York Review of Books had the courage to publish, noting that Kennedy's remarks had "as many bromides and banalities as any prize essay at a girl's school". Later biographies left nothing standing of the legend, and IF Stone said that Kennedy had been "an optical illusion". Maybe it was, of all people, Lyndon Johnson who had it right: "He never did a thing... It was the goddamnest thing... His growing hold on the American people was a mystery to me". But the ghost has rolled on: Obama was just two in 1963.

In his own words

"In the long history of the world, only a few generations have been granted the role of defending freedom in its hour of maximum danger. I do not shrink from this responsibility – I welcome it."

"Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country."

"It is an unfortunate fact that we can secure peace only by preparing for war."

In others' words

"A great and good president, the friend of all people of good will; a believer in the dignity and equality of all human beings; a fighter for justice; an apostle of peace." Earl Warren

"There was no trace of meanness in this man. There was only compassion for the frailties of others." Abraham Ribicoff

"He seized on every possible shortcoming and inequity in American life and promised immediate cure-alls." Richard M Nixon

"I sincerely fear for my country if Jack Kennedy should be elected president. The fellow has absolutely no principles. Money and gall are all the Kennedys have." Barry Goldwater

Minutiae

His right leg was 3/4 in longer than his left.

He lost his virginity at 17 in a Harlem brothel.

He was the only president whose father attended his inauguration.

On his 21st birthday he came into a $1m trust fund established for him by his father.

As a schoolboy he was nicknamed "rat-face".

During the 1960 campaign, he allegedly claimed to have received a telegram from his father saying: "Dear Jack, Don’t buy a single vote more than is necessary. I’ll be damned if I’m going to pay for a landslide."

He kept a dog called Pushinka. A gift from Khrushchev, it was a daughter of Strelka, one of the dogs sent into space on Korabl-Sputnik 2 in 1960. He called its puppies "pupniks".

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments