Comet Churyumov-Gerasimenko: This cosmic rubber duck holds the very elixir of life

Between them, Rosetta and the Philae lander should answer two of the most important questions in science

Imagine travelling through space for 11 years, hibernating for months in the depths of the Solar System until you finally awaken earlier this year as you home in on your goal. And then – when you arrive – you discover it’s totally rancid.

It smells of rotten eggs and horse manure, coupled with the acid-sharp tang of sulphur dioxide. The putrid stench is alleviated only by the tang of bitter almonds: but that’s a sign of deadly cyanide, which is mixed with scentless but poisonous carbon monoxide.

Disappointed? Want to go home? Not so the scientists behind Rosetta, Europe’s unmanned mission to a comet. They are elated. For this mix of chemicals – sniffed out for the first time at Comet Churyumov-Gerasimenko – is the very elixir of life. It’s probably the original material from which all living things have been made.

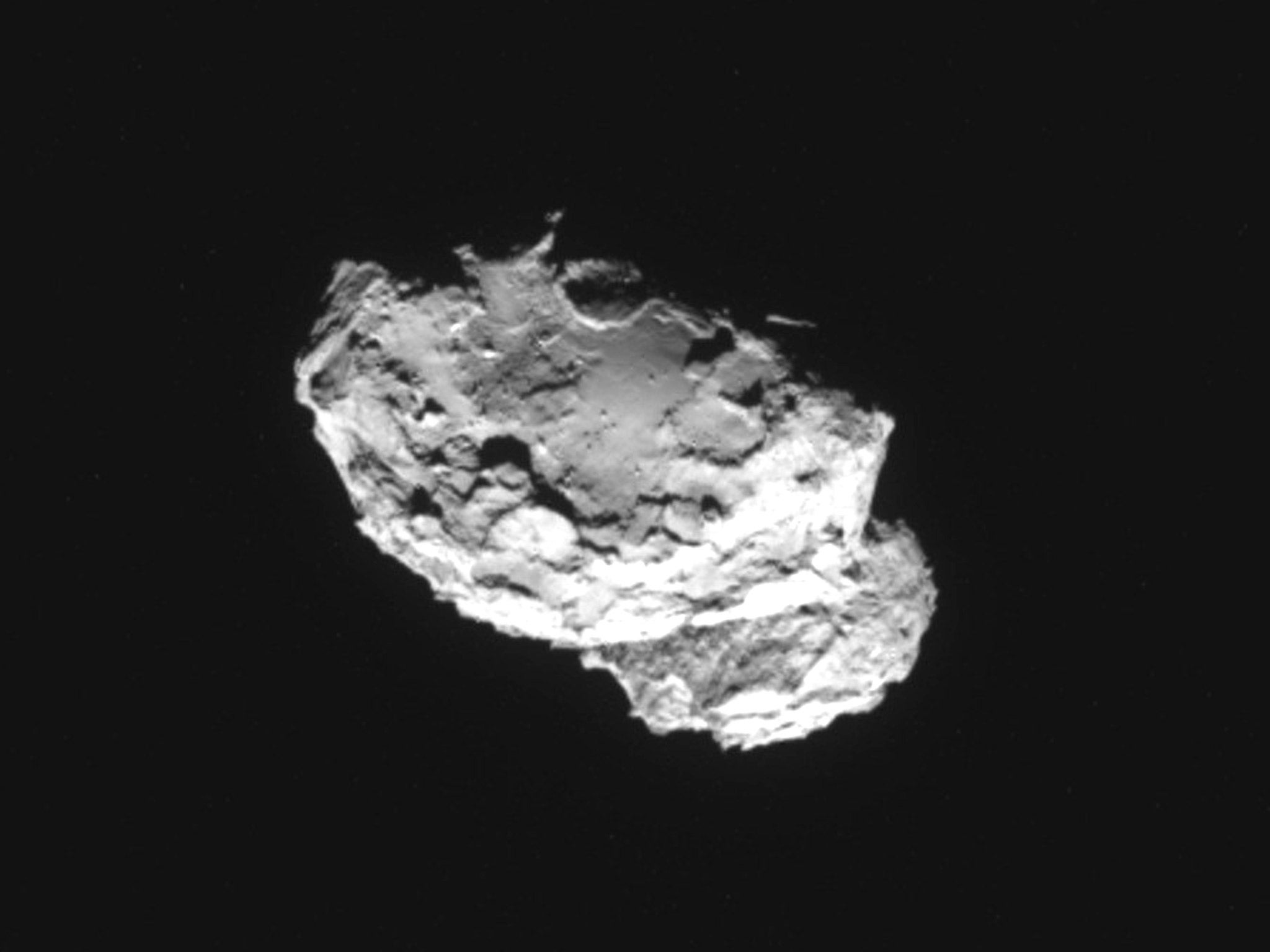

Rosetta arrived at Comet Churyumov-Gerasimenko in August. As well as sniffing the gas that’s erupting as the frozen comet feels the increasing heat of the Sun, the spacecraft has been sending back stunning postcards of its target. The comet looks like a rubber duck – in shape, though not in colour. It’s as black as coal.

Even the experts aren’t sure how the comet came to be this shape. The “head” and the “body” were perhaps separate icy objects that stuck together long ago, when the Solar System was born. Alternatively, the comet may have been a single object all along, with a layer of volatile material through its middle that’s evaporating until only a thin “neck” is left. Rosetta’s cameras are already showing steam boiling away from the neck region, so it’s only a matter of time till the duck’s head parts company from its body.

Video courtesy of The Open University

On 12 November, Rosetta drops a small lander on to the “head”. Here it will measure what the comet is made of – as well as taking snapshots of the eruptions all around it, as Churyumov-Gerasimenko heads for its closest encounter with the Sun next year. Between them, Rosetta and the Philae lander should answer two of the most important questions in science: where did Earth’s water come from; and – ditto – the carbon atoms that make up living things?

Most astronomers think Earth was baked dry billions of years ago, when a wayward planet impacted it, splashing out the rocks that made up the Moon – and leaving Earth as a ball of molten lava. After our planet cooled, perhaps the water we see in the oceans today deluged down from space, delivered by countless comets hitting Earth – along with the smelly molecules that are now getting up Rosetta’s scientific nose.

By checking out the blackened cosmic duck, we’ll be able to tell if it’s comets that we can thank for our existence on Earth.

What’s up

The faint, sprawling constellations of autumn dominate the heavens this month. November is a great chance to home in on the Andromeda Galaxy, our Milky Way’s nearest neighbour in extragalactic space. Some 2.5 million light years away, this giant spiral galaxy covers an area of the sky four times bigger than the Full Moon, and it’s easily visible to the unaided eye from a clear location. Binoculars will give you a great view of it, while a moderate-sized telescope reveals its two biggest satellite galaxies.

The Pleiades (Seven Sisters) are now well up in the November sky; and the icon of our colder months, the constellation of Orion, is putting in an appearance in the east.

The maximum of the Leonid meteor shower takes place on the night of 17/18 November. Expect to see up to 20 shooting stars per hour.

Planet-wise, it’s not a month to be getting out of bed for. Mars is skulking low in the south-west, setting at 7.20pm. Jupiter, on the borders of Cancer and Leo, rises around 10.30pm. It’s the brightest object in the night sky (after the Moon). But for those of you who are larks, there’s a treat in store. Little Mercury puts in its best morning performance of the year. Look out for it during the first three weeks of the month, low in the east at around 6am. But even with a telescope, you’ll be able to make out only a tiny disc.

Diary

Full Moon : 6 November, 10.23pm

Moon at Last Quarter: 14 November, 3.15pm

Maximum of Leonid meteor shower: 17/18 November

New Moon: 22 November, 12.32pm

Moon at First Quarter: 29 November, 10.06am

Your month-by-month guide to the night sky next year, Stargazing 2015 by Heather Couper and Nigel Henbest (Philip’s, £6.99)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks