What we discovered on the far side of the moon

Using our method, we can make more accurate estimations to determine the stability and strength of the soil for developing bases and research stations on the moon, writes Iraklis Giannakis

Seven months after it was launched, the US robotic rover Perseverance successfully landed on Mars on 18 February. The landing was part of the mission Mars2020 and was viewed live by millions worldwide, reflecting the renewed global interest in space exploration. It was soon followed by China’s Tianwen-1, an interplanetary Mars mission consisting of an orbiter, lander and rover called Zhourong.

Perseverance and Zhourong were the fifth and sixth planetary rovers deployed in the past decade. The first one was America’s Curiosity which landed on Mars in 2012, followed by China’s three Chang’E missions.

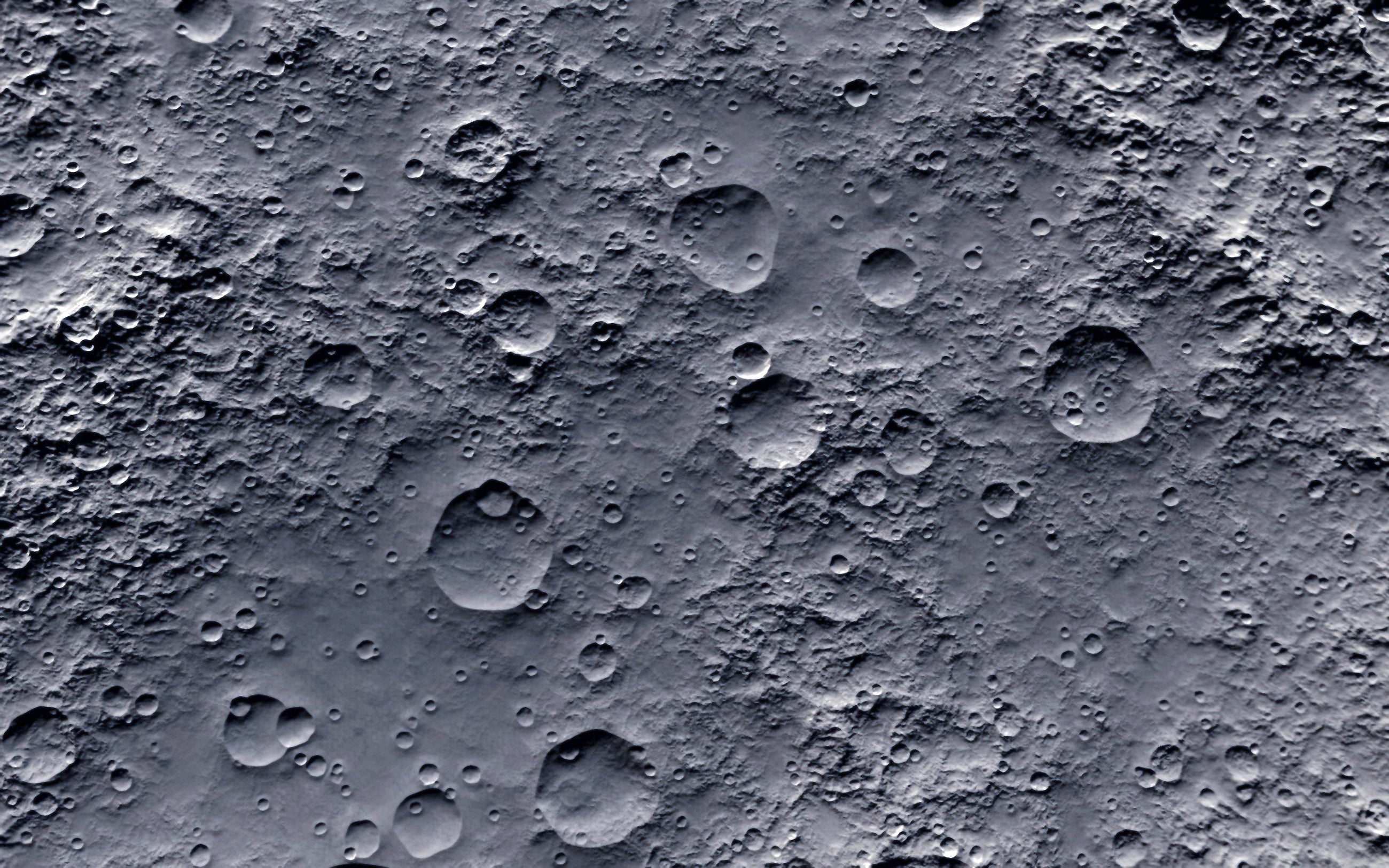

In 2019, the Chang’E-4 lander and its Yutu-2 rover were the first human objects landed on the far side of the moon – the side that faces away from the Earth. This marked a pivotal milestone, of equal importance to the Apollo 8 mission in 1968, when the far side of the moon was seen by humans for the first time.

To analyse the data captured from the Yutu-2 rover, which used ground-penetrating radar (GPR), we developed a tool that could detect in much greater detail the layers beneath the moon’s surface than had ever been done before. It was also able to provide insights into how it evolved.

The far side of the moon is of great importance due to its interesting geological formations but this hidden side also blocks all the electromagnetic noise from human activity, making it an ideal place to build radio telescopes.

Orbiter radars have been used for planetary sciences since the early 2000s but the recent Chinese and US rover missions were the first to use GPR on the site. This GPR is now set to become part of the scientific payload of future planetary missions, where it will be used to map the sub-surface of landing sites and shed light on what is happening below the ground.

GPR also has the ability to retrieve significant information regarding the type of soils and their sub-surface layers. This information can be used to get an insight into the geological evolution of an area and even assess its structural stability for future bases and research stations.

This newly discovered complex, layered structure also suggests that small craters are more important and may have contributed much more than believed to the materials deposited by meteorite strikes

Perseverance and Tianwen-1 are currently active, and the first GPR images from Mars are expected to be published in 2022. But the first available on-site GPR data was from the Chang’E-3, E-4 and E-5 lunar missions, in which it was used to investigate the structure of surface layers of the far side of the moon and provide valuable information about the geological evolution of the area.

Despite the benefits of GPR, one major drawback is its inability to detect layers with smooth boundaries between them. This means gradual variations from one layer to another go undetected, giving the false impression that the sub-surface consists of a homogenous block, while in fact it may be a much more complex structure representing a completely different geological history.

Our team developed a new method capable of detecting these layers by using the radar signatures of hidden rocks and boulders. The newly developed tool has been used to process the GPR data captured by Chang’E-4’s Yutu-2 rover which landed in the Von Karman crater, part of the Aitken Basin at the moon’s south pole.

The Aitken basin is the biggest and oldest-known crater, believed to have been created by a meteoroid impact that penetrated the crust of the moon and uplifted materials from the top mantle (the interior layer just below it). Our detection tool revealed a previously unseen layered structure in the first 10 metres of the lunar surface, which had been understood to be one homogenous block.

Using our method, we can make more accurate estimations regarding the depth of the top surface of lunar soil, which is an important way to determine the stability and strength of the soil foundation for developing lunar bases and research stations.

This newly discovered complex, layered structure also suggests that small craters are more important and may have contributed much more than believed to the materials deposited by meteorite strikes and the overall evolution of lunar craters.

This means we will have a more coherent understanding of the complex geological history of our satellite and enable us to predict more accurately what lies beneath the surface of the moon.

Iraklis Giannakis is a lecturer in geosciences at the University of Aberdeen. This article first appeared on The Conversation.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies