Four years of excruciating seizures caused by the 1cm tapeworm found burrowing through a man's brain

Only 300 cases of Spirometra erinaceieuropaei have been reported worldwide - and never in Britain

Health warning: people of a nervous disposition may find the following medical report disturbing.

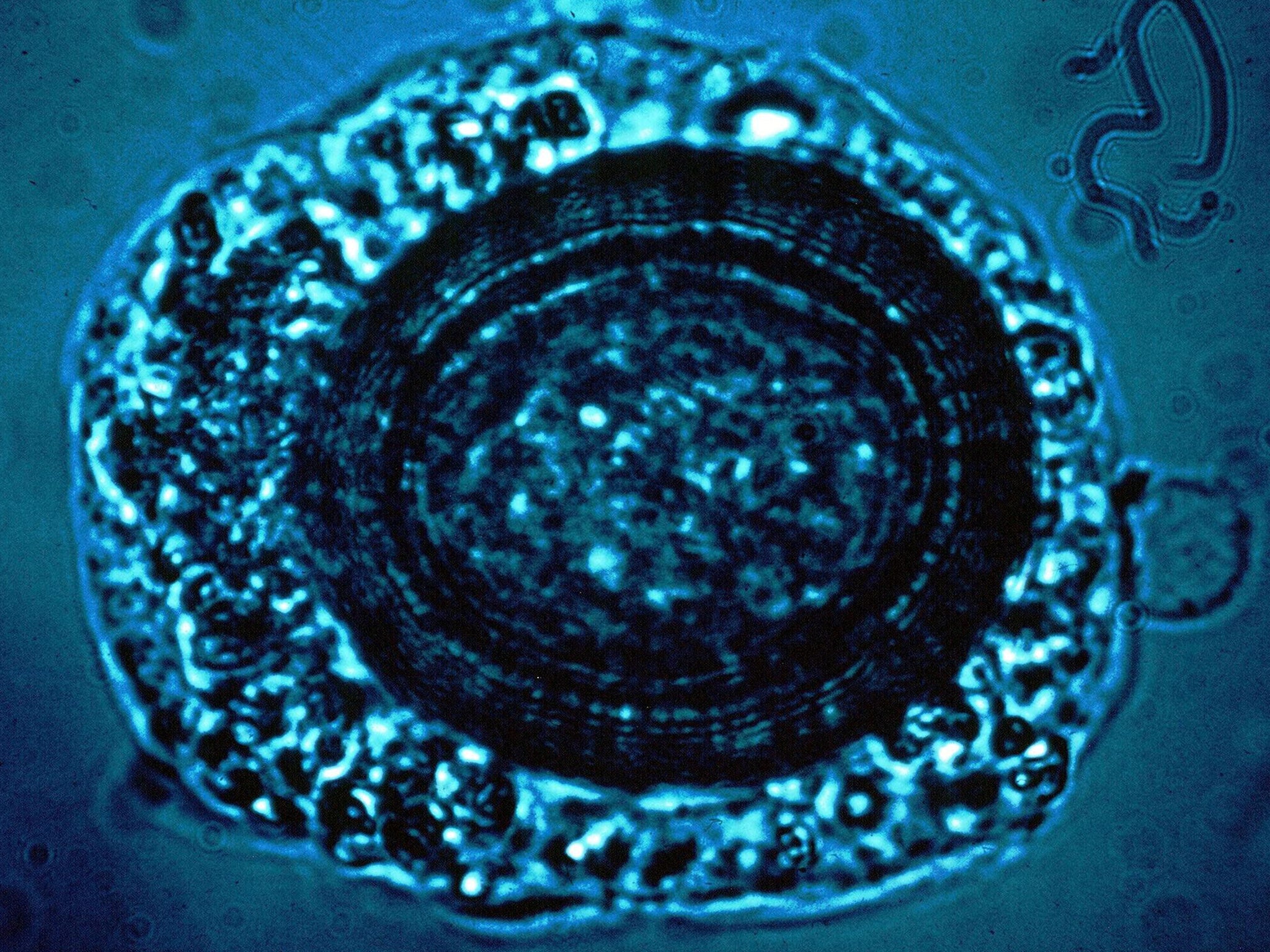

It started with headaches, memory flashbacks and a strange sense of smell. It ended with doctors pulling a 1cm-long worm from the brain of man who had lived unwittingly with the parasite for at least four years.

The 50-year-old patient complained of various neurological symptoms including seizures and a progressive pain on his right side, which turned out to be a tapeworm burrowing from one side of his brain to the other.

Doctors at Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge recovered the tapeworm during an exploratory operation after an MRI scan had indicated that something worm-like could be behind the patient’s deteriorating condition.

Scientists at the nearby Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute carried out a genome analysis and found that the tapeworm belonged to a species called Spirometra erinaceieuropaei, which had never been seen before in Britain – and only 300 cases of which have been reported worldwide since 1953.

During the four years that the patient was known to be suffering from symptoms, the worm had wriggled at least 5cm from one side of the brain to the other, crossing a sensory structure called the thalamus, scientists said.

The patient, a Chinese-born man who has lived in Britain for the past 20 years, has recovered well after surgery with the help of an anti-tapeworm drug. It is not known how he became infected, although it is likely to have been during one of his frequent visits to China, the researchers said.

“We did not expect to see an infection of this kind in the UK, but global travel means that unfamiliar parasites do sometimes appear,” said Effrossyni Gkrania-Klotsas, an infectious disease specialist at Addenbrooke’s NHS Trust.

“We can now diagnose sparganosis using MRI scans, but this does not give us the information we need to identify the exact tapeworm species and its vulnerabilities,” Dr Gkrania-Klotsas said.

“Our work shows that, even with only tiny amounts of DNA from clinical samples, we can find out all we need to identify and characterise the parasite,” she added.

The tapeworm has a complex life cycle involving two or three different host species. The patient could have become infected in a number of ways, either by eating infected fresh-water crustaceans or the undercooked meat of reptiles and amphibians, or possibly by using a Chinese remedy for sore eyes that involves a poultice made of raw frogs, the researchers said.

“We don’t know how it got into him. There is very little known about how it infects humans, and it can go anywhere once inside the body, [even] the eyeball or brain,” said Hayley Bennett of the Sanger Institute, the lead author of the study published in the journal Genome Biology.

“It can do a lot more damage when it’s in the brain, obviously. It managed to live for so long because we think it absorbs nutrients from the surrounding tissues,” Dr Bennett said.

“It remained in its larval form because it doesn’t develop into an adult when inside humans. This shows that humans are really an unintended, dead-end host for the parasite,” she said.

The ribbon-shaped worm did not have mouthparts or the tiny hooklets used as anchors, the usual adornments of adult tapeworms, but it nevertheless managed to live for several years on whatever food it found within the man’s head.

Its genome turned out to be about 10 times bigger than comparable tapeworms, and just a third of the size of the human genome. However, much of its DNA is filled with repetitive sequences that appear to be largely redundant, Dr Bennett said.

“We only had a minute amount of DNA available to work with, just 40 billionths of a gram. So we had to make difficult decisions as to what we wanted to find out from the DNA we had,” she said

“It was really quite unexpected to find that it has such a big genome. It has a lot of genes for proteases, the enzymes used to break down proteins,” she added.

Studying the genomes of parasites allows scientists to explore new ways of developing drugs and other forms of treatment, said Matt Berriman of the Wellcome Trust, a senior author of the scientific paper.

“For this uncharted group of tapeworms, this is the first genome to be sequenced and has allowed us to make some predictions about the likely activity of known drugs,” Dr Berriman said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments