Not to be sniffed at: The human nose can distinguish between over one trillion odours - a billion times more than we'd thought

A typical person can smell at least one trillion different odours – a billion-fold greater than previously thought – according to the first scientific study to accurately estimate the olfactory power of the human nose.

The remarkable and unforeseen ability of the nose to distinguish between different kinds of odour has been revealed in a pioneering study showing that humans are not to be sniffed at when it comes to the sense of smell.

It has been widely accepted for nearly a century that humans are able to discriminate between no more than about 10,000 odours, but the latest findings show that the true number is much greater, conservatively estimated at one trillion, or 1,000,000,000,000.

This would make the human sense of smell more discriminatory than human colour vision, which can distinguish between 2.3 million and 7.5 million colour variations, or human hearing, which can discriminate between about 340,000 sound tones.

“We have debunked an old idea that humans can only smell about 10,000 odours and we’re the first to come up with an accurate number, which is far, far higher than anyone had calculated,” said Professor Leslie Vosshall of the Rockefeller University in New York.

“The nose is really like a massive broadband technology that can take in huge amounts of information and pass it on to the brain. It is the only part of us that connects directly to the brain,” Professor Vosshall said.

“Our analysis shows that the human capacity for discriminating smells is much larger than anyone anticipated. Everyone in the field had the general sense that this number was ludicrously small, but [we were] the first to put the number to a real scientific test,” she said.

The 10,000 figure came from a 1927 study which had not been seriously challenged until now. “Objectively, everybody should have known that the 10,000 number had to be wrong,” Professor Vosshall added.

The latest study, published in the journal Science, involved the creation of unique combinations of smells derived from mixtures of 128 odour molecules derived from scents such as orange, anise and spearmint.

Volunteers were asked if distinguish between different combinations of these odour mixtures, which were made from groups of 10, 20 or 30 different odour molecules.

The volunteers were given three vials to smell, two of which were identical, and were asked to pick the odd one out. The third vial started out the same as the other two but was gradually altered to become more different. This enabled the scientists to gradually manipulate the molecular composition of each odour to eventually make it different enough for the nose to make a clear distinction.

Each of the 26 volunteers – 17 women and nine men – had to make 264 comparisons and, from these combined results, the scientists were able to make an extrapolation that gave them a conservative estimate of the overall olfactory power of the human nose.

“Our trick is we use mixtures of odour molecules, and we use the percentage of overlap between two mixtures to measure the sensitivity of a person’s sense of smell,” said co-author Andreas Keller of Rockefeller’s laboratory of neurogenetics and behaviour.

“We didn’t want them to be explicitly recognisable, so most of our mixtures were pretty nasty and weird. We wanted people to pay attention to ‘here’s this really complex thing – can I pick another complex thing as being different?’,” Dr Keller said.

“The message here is that we have more sensitivity in our sense of smell than we give ourselves credit. We just don’t pay attention to it and don’t use it in everyday life,” he said.

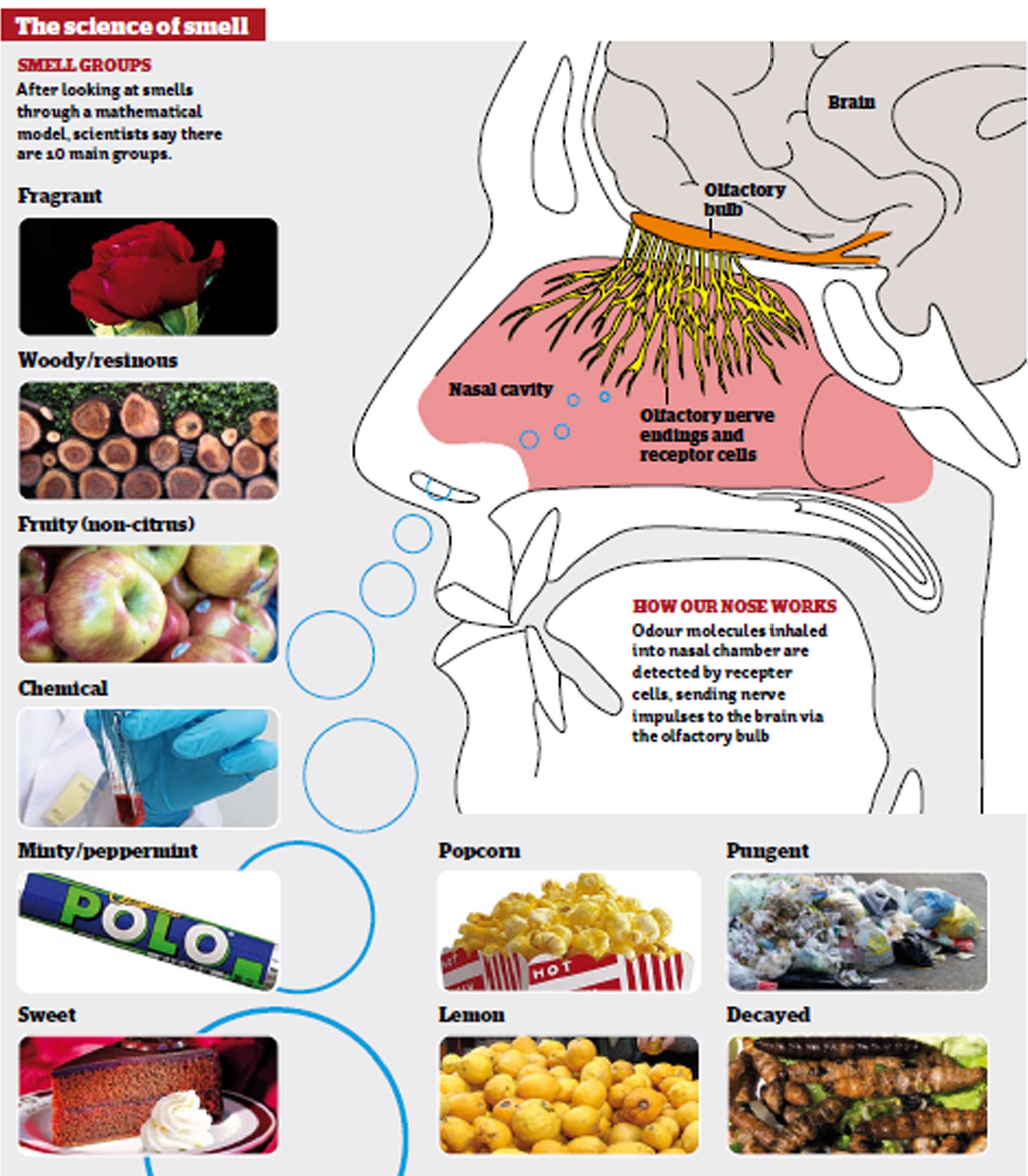

Human smell relies on two small odour-detecting patches in the upper nasal chamber each containing about five or six million receptor cells – comprising of 400 receptor types – which send signals directly to the brain via the olfactory bulb, attached to the base of the brain.

By comparison, the rabbit has 100 million olfactory receptor cells and the dog has some 220 million. This helps to explain why humans are much poorer at smelling than other animals, Professor Vosshall said.

“We show that humans have a good sense of smell that’s not been appreciated before but other animals are still better – rats are better than humans, but humans are still pretty good,” she said.

“I like to think that it’s incredibly useful to have that capacity, because the world is always changing. Plants are evolving new smells. Perfume companies are making new scents.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments