Philae lander data show comets could have brought 'building blocks of life' to Earth

The finding is further evidence in support of the theory that comets may have deposited the building blocks of life on the surface of the early Earth

Organic molecules that could have contributed to the chemical building blocks of life have been discovered under the icy surface of a comet, scientists have said.

An instrument on board the small robotic laboratory Philae which landed on the comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko last November has detected an organic polymer with a similar composition of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen found in the biological molecules of living organisms, they said.

The finding is further evidence in support of the theory that comets may have deposited the building blocks of life on the surface of the early Earth some 4.5bn years ago, effectively creating the “primordial soup” that kick-started evolution said Ian Wright, a planetary scientist at the Open University.

“What we are looking at here is frozen primordial soup and we believe that life evolved from something called primordial soup, but the trouble is it no longer exists on Earth. This comet’s primordial soup has been frozen for about 4.5bn years,” Dr Wright said.

“We have long speculated about the composition of comets but now we can put some names to the compounds that are actually there and it helps to explain how comets may have contributed to the organic compounds that they may have brought to Earth,” he said.

The Philae lander managed to collect data on the composition of the dust just beneath the comet’s surface about 20 minutes after it landed, when its batteries were still capable of sending the information back to the Rosetta mother ship orbiting overhead.

A mass-spectroscopy instrument on the lander analysed the material in the icy dust of the comet and detected a signal for polyoxymethylene, a long-chain molecule or polymer made up of repeating units of formaldeyde, one of the simplest organic molecules.

“The ratio of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen in this compound is the same as in many important compounds used in living organism, such as ribose sugar which is used to make biological molecules such as DNA and RNA,” Dr Wright said.

Philae was the first man-made object to make a soft landing on a comet, and although previous comet encounters, such as the 1986 flyby of Halley’s Comet by the Giotto spacecraft, have suggested the presence of organic polymers, none had actually made a direct detection from the surface.

“This is the first faltering steps towards getting to grips with what is actually there,” Dr Wright said.

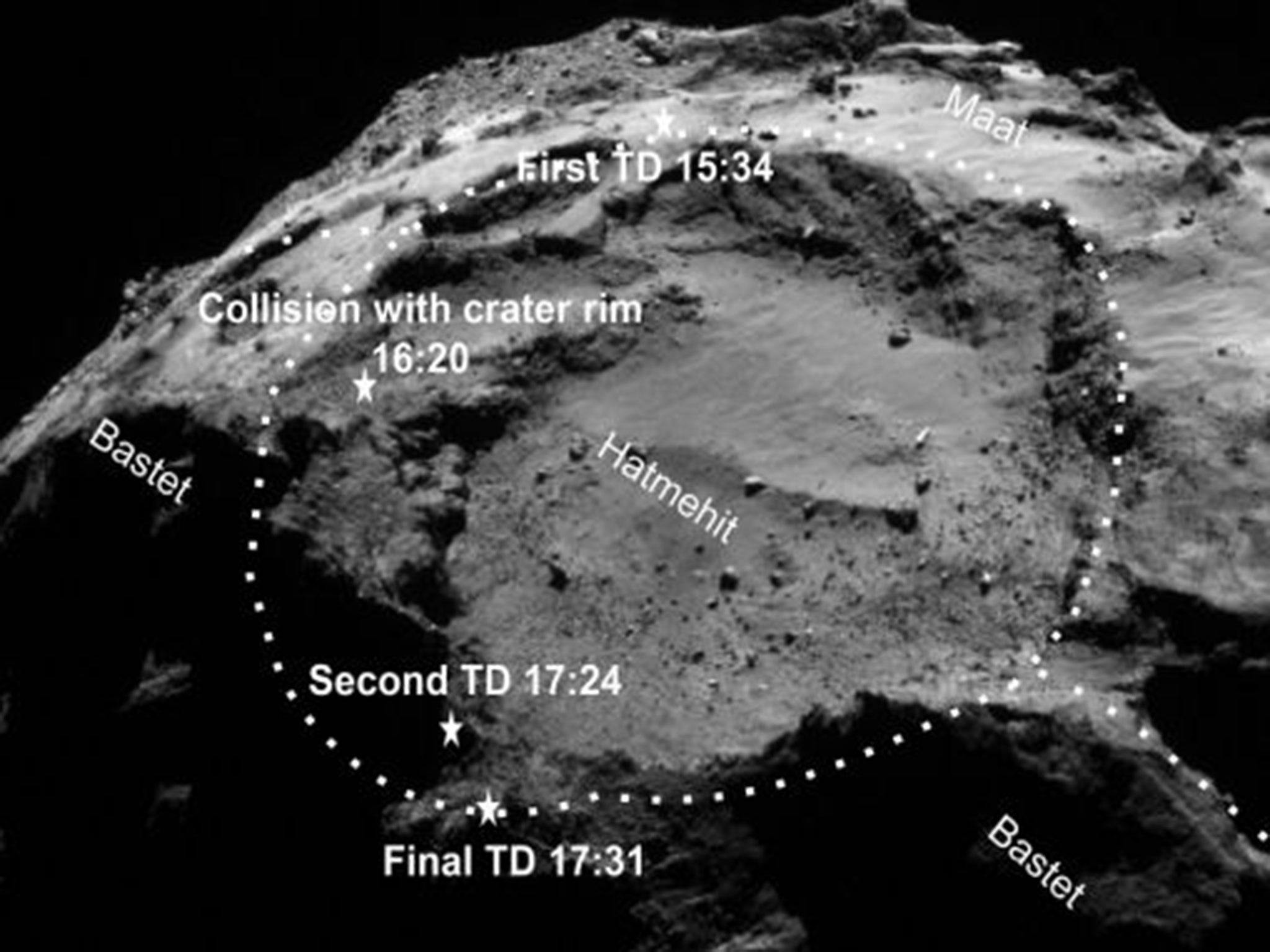

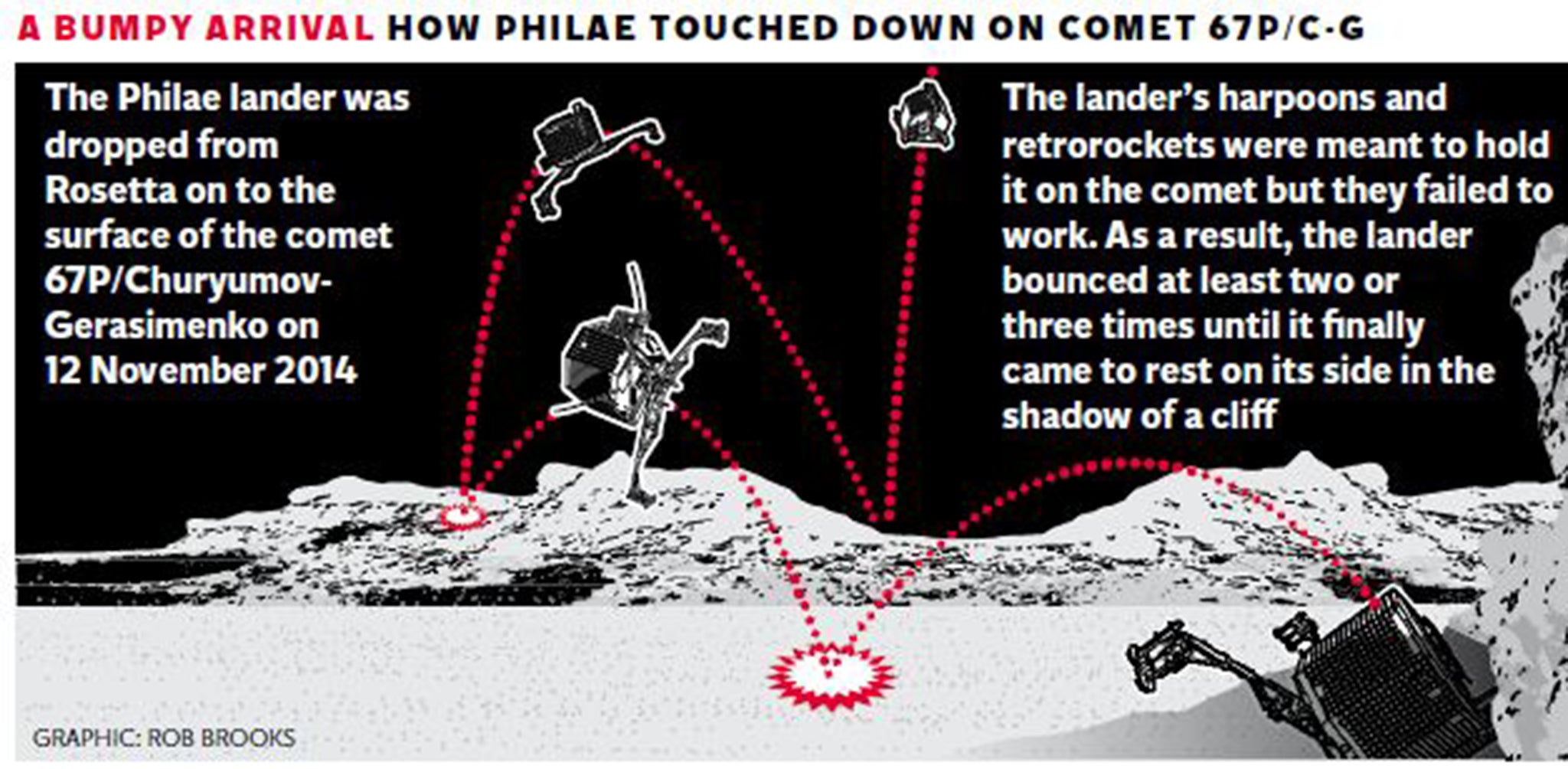

Philae was designed to collect data over many months using a range of instruments but it bounced several times from its original landing site, finally coming to an uneven rest in the shadow of a rock or cliff-face. Its solar panels were unable to charge the on-board batteries, which ran out of power after three days.

However, as the comet continued to edge closer to the Sun, Philae re-emerged from its hibernation briefly on 13 June after a partial re-charge of its batteries. It subsequently made contact with the Rosetta spacecraft six more times over 10 days, however it has not been heard of since its last transmission on 9 July.

The plan was to analyse samples of the comet deep under the surface but both of the lander’s drills failed to be deployed. However, Dr Wright believes that the landing disturbed the comet surface enough for the mass spectrometer to analyse material beneath the outmost layer of dust.

Six other studies, published in the journal Science, from the instruments on board Philae have produced the first detailed account of a comet from such a close range. An experiment using radio waves, for instance, found that between 75 per cent and 85 per cent of the comet’s interior is nothing but a void of space, suggesting that the “icy dust” that makes up the comet is loosely packed.

Philae’s first contact with the comet caused it to bounce quite high before it landed again about an hour later. It bounced at least once more before finally coming to rest about an hour and ten minutes after its initial contact with the comet.

Measurements show that the surface of a comet is composed of granular particles about 25cm (9.8ins) thick with a harder layer below. Daytime surface temperatures of the comet range from minus 143C to minus 183C.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks