Revolutionary new scan shows key to migraines is in the genes

A revolutionary way of screening the entire human genome for the genetic signposts of disease has produced its latest success – the first inherited link to common migraine and a possible reason for extreme headaches.

The technique, which scans all 23 pairs of human chromosomes in a single sweep, has found the first genetic risk factor that predisposes someone to the common form of migraine, which affects one in six women and one in 12 men. The discovery has immediately led to a new possible cause of migraine by alerting scientists to DNA defects involved in the build-up of a substance in the nerves of sufferers that could be the trigger for their migraines.

Scientists believe the findings could lead both to a better understanding as well as new treatments for the chronic and debilitating condition which is estimated to be one of the most costly brain-related disorders in society, causing countless lost working days.

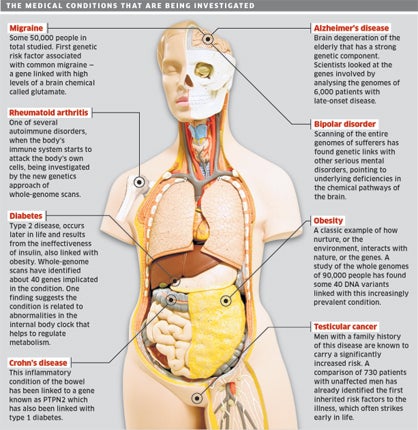

Scanning the entire blueprint of human DNA by genome-wide association studies (GWAS) has had a profound effect on the understanding of a range of other medical conditions over the past few years, from heart disease and obesity to bipolar disorder and testicular cancer. The study of migraine, published in the journal Nature Genetics, was an archetypal example of the new approach of medical genetics using the GWAS technique. Scientists analysed the genomes of some 5,000 people with migraine and compared their DNA to that of unaffected people to see if there were any significant differences that could be linked statistically to the condition.

The GWAS test uses arrays of specially designed fragments of DNA that could identify different sets of "markers" or genetic signposts in a person's genome. By analysing thousands of genomes, the scientists are able to build up a picture of DNA markers in a patient's genome pointing to the presence of defective genes that could predispose someone to migraine or any other common illness known to have a genetic element.

"This is the first time we have been able to peer into the genomes of many thousands of people and find genetic clues to understand common migraine," said Dr Aarno Palotie, chair of the international headache genetics consortium at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in Cambridge. "Studies of this kind are possible only through large-scale international collaboration so that we could pick out this genetic variant. This discovery opens new doors to understanding common human diseases."

The scientists behind the migraine study scanned the entire genomes of some 50,000 people in total, a huge undertaking that was only possible because of the availability of relatively cheap commercial GWAS kits that can be used to screen all of a person's 46 chromosomes in a single sweep.

The insight that this approach has given scientists could only be dreamed of 10 or 15 years ago. Suddenly, it is becoming possible to tease out the influences of the many different genes that may be involved in raising the risk of developing a particular condition, whether it is heart disease or Alzheimer's. A decade or two ago, this genetic component to common diseases was only known about from a person's family history of disease.

The children of parents who had both died of heart disease were known to be statistically more likely to die of the disease themselves, but the nature of the genes involved in causing this predisposition was largely a mystery until GWAS came along.

"I think it has revolutionised the way we can tackle these diseases. We've identified new pathways to disease and new possible causes that we did not know before," Dr Palotie said.

"It's like the difference between night and day, between black-and-white photographs and colour pictures," he added.

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, which led much of the effort to decode the human genome, has been an eager pioneer of the GWAS technique and has established many initiatives over the past few years to exploit its revolutionary potential for teasing out the genetic components of common diseases – the "nature" in the nature-nurture debate.

At the Sanger Institute alone, GWAS is being used to find the genetic variants of heart disease, cholesterol levels, bipolar disease, breast and testicular cancers, high blood pressure, Crohn's disease, rheumatoid arthritis and type 2 diabetes.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies