Stargazing in June: From the summer solstice to a cosmic embrace

Two of our solar system’s most sensational planets will get together for a tryst

Dawn on 21 June will see the ancient megaliths of Stonehenge bustling with white-robed Druids intent on viewing the Sun rising behind the outlying Heel Stone – just as our ancestors did millennia ago when they raised this vast structure to celebrate midsummer’s morning. Or did they? The dead pigs say otherwise ...

Let’s start by winnowing out the mythical chaff from the factual wheat. The Druids didn’t build Stonehenge; they came on the scene about 2,000 years later, and – according to the Roman writer Pliny – they didn’t worship in stone temples but in ‘‘forests of oak’’.

It was only in the 7th century that the antiquarian John Aubrey associated the Druids with Stonehenge. In 1740, a fellow neo-Druid called William Stukeley measured Stonehenge, and realised that its central line pointed ‘‘full northeast, being the point where the sun rises at the summer solstice’’. At that point, the link between Stonehenge, the Druids and the midsummer sunrise was set in tablets of stone.

But hang on. Instead of standing in the centre of the great stone circle and looking outwards, you could equally well place yourself at the Heel Stone and look through the centre of Stonehenge, towards the south-east. That’s the direction where the Sun sets, at midwinter.

In fact, Stukeley’s original account describes this bearing, with ‘‘the principal diameter or groundline of Stonehenge, leading from the entrance up to the middle of the temple to the high altar’’. So why did he choose the opposite direction as being critical to the Druids?

Stukeley was a Freemason. For Masons, the western part of the sky is the direction of death. The north-east is spiritually all-important because it is the point where the Sun rises on the feast of St John (the traditional Christian date for midsummer, on 24 June).

That’s why Stukeley picked out midsummer as the key season for Stonehenge. There’s no reason, though, to believe that our distant ancestors felt the same way. In fact, there are two great monuments in the British Isles which are unambiguous markers for the solstice, because they contain deep passageways that are lit up by Sun only once a year. In the case of Newgrange in Ireland and Maeshowe in Orkney, that date is the winter solstice.

Now archaeologists have provided the clinching evidence that Stonehenge, too, was erected to mark midwinter’s day. Mike Parker Pearson has excavated Durrington Walls, a huge settlement near Stonehenge. Here he’s found the remains of orgiastic feasts: bones of cows and pigs that had been brought vast distances – some from Cornwall, and others from the far north. Clearly, people came from all over the country to hold ceremonies at Stonehenge.

And the bones reveal the season that they travelled. The growth of the pigs’ teeth, and the amount they had worn, showed that they had been slaughtered for the table at the age of nine months. Given that piglets are naturally born in the spring, Parker Pearson is adamant that people were ‘‘feasting on pork at midwinter most likely around the midwinter solstice’’.

So, if you want to truly celebrate as our ancestors did, don’t go to Wiltshire this month. Instead, go to Stonehenge on 22 December, to view the sun setting behind the giant portals of stone.

What's Up

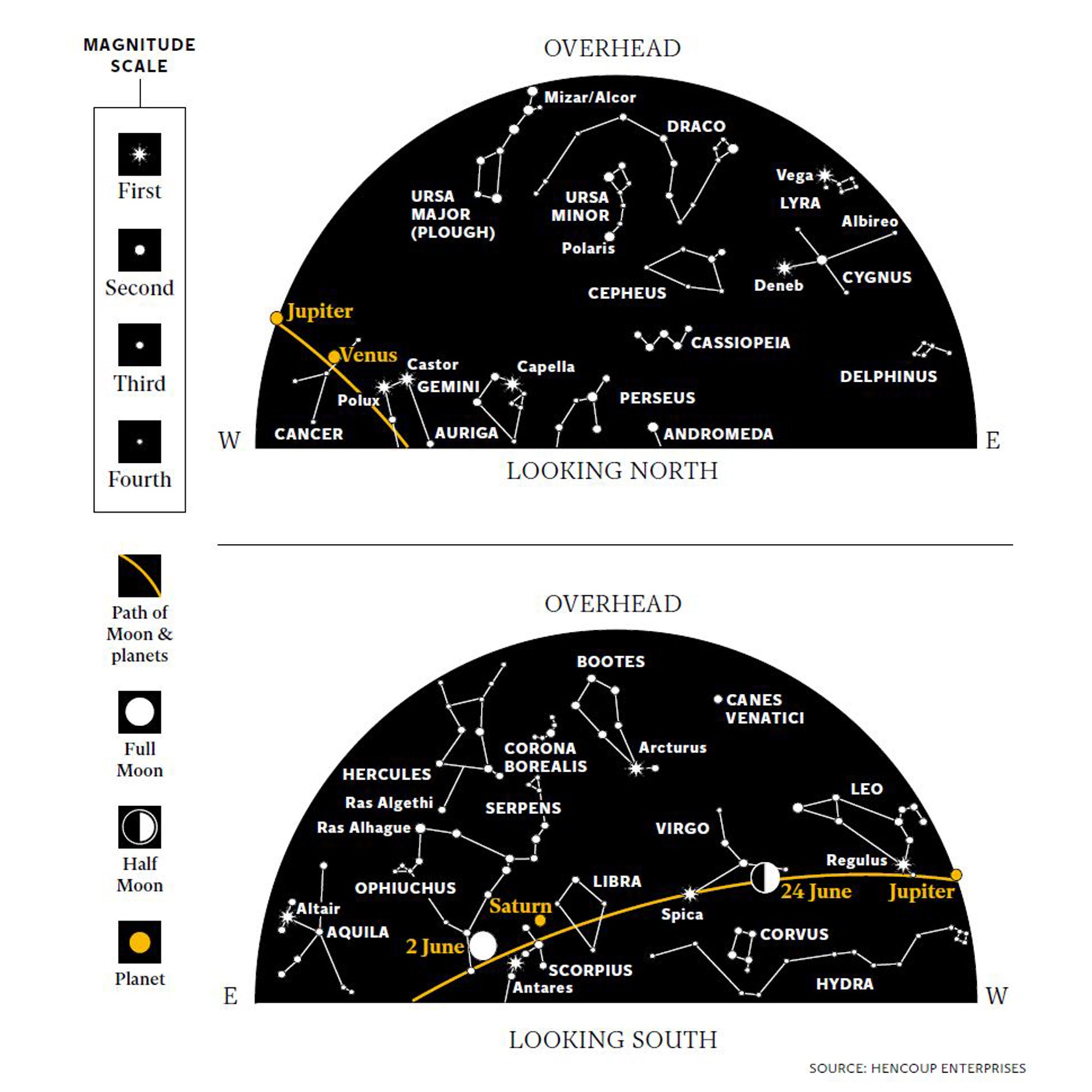

This month, two of our solar system’s most sensational planets are about to get together for a tryst. For the whole of spring, luminous giant Jupiter has been lighting up our evening skies. But dazzling Venus – Earth’s twin in size – has been sneaking up in the opposite part of the sky. Our neighbour world, cloaked in a dense atmosphere of carbon dioxide, reflects sunlight amazingly: it is the brightest object in the sky after the Sun and Moon.

On 30 June, the two brilliant worlds tangle in a cosmic embrace. Separated by a space less than the diameter of the moon, Jupiter and Venus will make a stunning sight low in the western sky. Otherwise, the summer constellations are making their appearance. Orange Arcturus, in Boötes, lords it over the night skies. Next to it, the small-but-perfectly-formed Corona Borealis – the Northern Crown – is a beautiful reminder that warmer days are on the way.

What to look out for

1 June: 5.19 pm: full moon

6 June: Venus at greatest eastern elongation

9 June 4.42 pm: moon at last quarter

16 June 3.05 pm: new moon

24 June 12.03 pm: moon at first quarter; Mercury at greatest western elongation

30 June: Venus and Jupiter close conjunction

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments