Three-parent babies: ‘As long as she’s healthy, I don’t care’, says mother of IVF child

Sharon Saarinen gave birth to Alana after four failed IVF attempts. But doubts remain about the technique her clinic used

In May 1997, the first child was born as a result of a controversial IVF technique which involved mixing the genes of three people. Today, Emma Ott, of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, is a healthy American teenager who routinely scores straight As at high school.

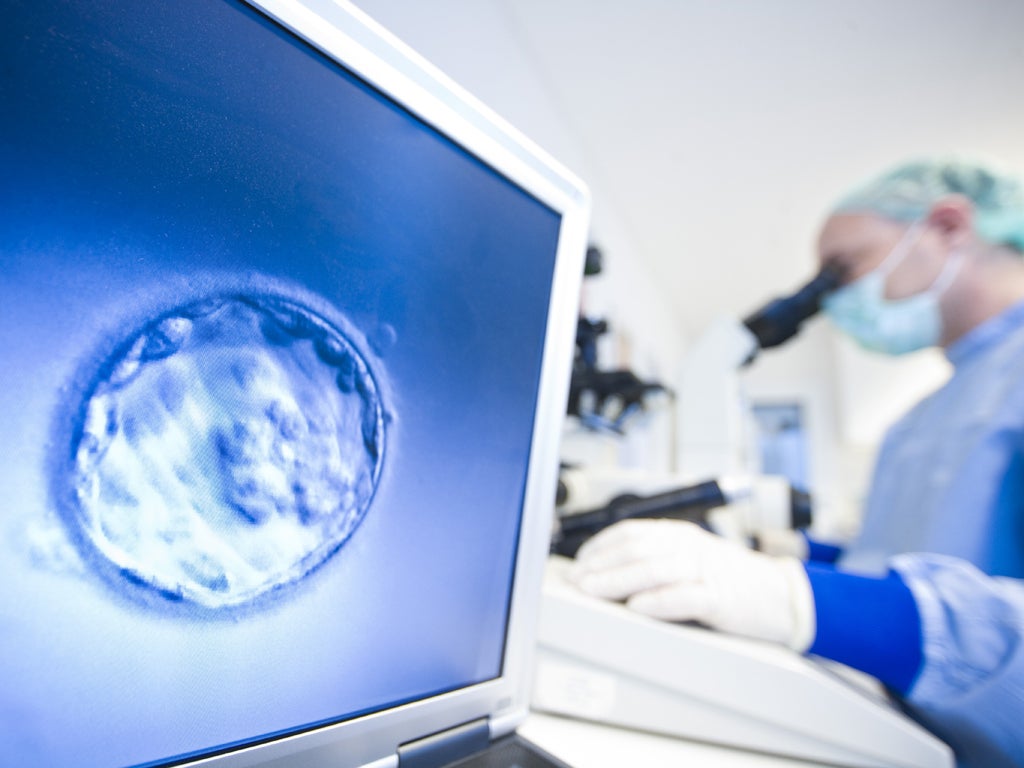

She was one of 17 IVF babies born after cytoplasmic transfer, when a small quantity of cytoplasm – the jelly-like material outside the cell nucleus – from a healthy donor egg was injected into an egg cell of her mother before being fertilised in vitro with her husband’s sperm.

The only other child from the group who has been publicly named is Alana Saarinen, 13, of West Bloomfield, Michigan, whose mother Sharon underwent cytoplasmic transfer of her IVF embryos in 2000 when she was 36 after four failed IVF attempts.

“I think it was the only thing that helped me. If there were risks, it didn’t matter. I wanted a child too much at that point,” Mrs Saarinen told The Independent. “It was definitely the right thing to do.”

Jacques Cohen, who was then at the Institute for Reproductive Medicine and Science at Saint Barnabas Medical Centre in New Jersey, had pioneered cytoplasmic transfer as a way of boosting the chances of a successful IVF cycle. It was thought that the extra cellular material from the donor egg helped the mother’s egg to fertilise and develop into a viable IVF embryo.

But in the process, some of the cytoplasm’s mitochondria – the microscopic “power packs” of the cell – would have also been transferred, along with the 37 genes encoded within the self-replicating DNA molecule carried inside each mitochondrion.

This means that Emma and Alana, along with the 15 other St Barnabas teenagers, very likely inherited DNA from three people: the mitochondrial DNA of the woman who donated the egg for cytoplasmic transfer, as well as their mothers’ mitochondrial DNA and both parents’ nuclear DNA carried in the chromosomes.

It is not known how many of the transferred mitochondria would have survived and replicated within the developing embryos. Tests on Emma failed to find any “third party” mitochondrial DNA, while Alana has never been tested.

“She’s not been tested because as long as she’s healthy, I don’t care,” Mrs Saarinen said.

But in at least two other children Dr Cohen did find mitochondrial DNA from two “mothers”.

Blood tests on two of the IVF babies revealed they carried mitochondria from two women, which would mean that these babies, if they were female, could pass on this mixture of mitochondrial genes to their own children – our mitochondria are inherited from our mothers only.

In effect, this was germ-line genetic modification because it meant that this mix of genes would be inherited by subsequent generations through the maternal line.

When news of the creation of “GM babies” emerged in 2001, it created headlines around the world because it effectively meant that scientists had carried out a form of “germ-line” genetic modification on humans for the first time – something that was illegal in Britain.

The notion that this was germ-line genetic modification was not hidden in Dr Cohen’s scientific paper, published in the journal Human Reproduction in May 2001. The summary or abstract at the start of the study ended with the stark sentence: “This report is the first case of human germ-line genetic modification resulting in normal healthy children.”

This explosive revelation has come to haunt Dr Cohen, and indeed the whole field of mitochondrial transfer. The Department of Health, for instance, ruled earlier this year that the Government does not define mitochondrial donation as a form of genetic modification, although it accepts that it is germ-line therapy that will affect future generations.

The department argued that the 37 genes of the mitochondria are only involved in energy production within the cell and have nothing to do with personality or physical traits, so it is wrong to say that mixing mitochondria would result in “GM babies”.

When we asked Dr Cohen whether cytoplasmic transfer, with its inherent risk of creating babies with genes from three people, was a form of genetic modification, he replied in an email: “A good question! I personally do not think it was, because no genes were altered.”

Then why did the scientific paper state that this was the first example of genetic modification, we asked in reply.

“[It] only appeared in the abstract. It had appeared in the paper as well when it was drafted, but the discussion was removed after debate among the authors before the paper was submitted. The language in the abstract should have been removed during the printing process. This was an oversight,” Dr Cohen explained in a subsequent, and final, email exchange.

In fact, this is not quite right. The discussion section of the paper clearly states: “These are the first reported cases of germ-line mtDNA [mitochondrial DNA] genetic modification which have led to the inheritance of two mtDNA populations in the children resulting from ooplasmic [egg cytoplasm] transplantation.”

It continued: “These mtDNA fingerprints demonstrate that the transferred mitochondria can be replicated and maintained in the offspring, therefore being a genetic modification without potentially altering mitochondrial function.”

Whether or not the technique of cytoplasmic transfer amounted to germ-line genetic modification, the publicity it generated in 2001 stirred the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to crack down on the private fertility clinics where it was being offered.

In 2002, the FDA informed IVF clinics that using a third person’s cytoplasm, and the mitochondria contained in this cellular material, would require an Investigational New Drug (IND) application, because it was effectively a new and untested treatment. The administration threatened Dr Cohen and the other IVF clinics with “enforcement action” over “therapy involving the transfer of genetic material by means other than the union of [sperm and egg]”.

“This is the same permit format used to license new medical drugs,” Dr Cohen explained.

“We applied to have our procedure licensed and went through the pre-IND process in 2002 and 2003. The FDA was helpful and intelligent. In 2003, the IVF clinic went private and the research team moved elsewhere. The permit process was ceased, because funding was lost,” he said.

A decade later, in February 2014, the FDA looked again at the issue of cytoplasmic transfer in IVF because of the new interest in the United States over mitochondrial donation, the so-called “three-parent” embryo technique being considered in Britain involving the wholesale transfer of mitochondria from one egg cell to another.

In its review of mitochondrial donation, the FDA highlighted its concerns over the 17 babies born as a result of cytoplasmic transfer. It cited reports of two instances of Turner syndrome, where children are missing one of their two sex chromosomes, and one instance of pervasive developmental disorder, a classification which includes autism.

“However, the sample size was too small to draw any reliable conclusions concerning the relationship of the cytoplasmic transfer method to the occurrence of disorders in the children,” the FDA said.

Dr Cohen said that none of the 17 IVF children was actually born with Turner syndrome, and that the FDA was referring to two unborn foetuses where it was diagnosed – one was miscarried and the other, a twin, aborted.

“[A missing sex chromosome] is the single most common anomaly found in early pregnancy. Whether these anomalies were related to the procedure is unknown,” he said.

“The fact is that the parents could not become pregnant on their own or after conventional IVF. This could have also been the cause of the [missing sex chromosome],” he added.

As for the instance of pervasive development syndrome diagnosed in one of the 17 babies in the first year of life, Dr Cohen is adamant that this, too, could have just been a coincidence. “Male twins have a significantly higher rate of pervasive developmental disorders; however whether the outcome was related to cytoplasmic transfer is unknown,” he said.

What happened to this child and the rest of the children since then is not known. Now, it seems, the Institute for Reproductive Medicine and Science at Saint Barnabas Medical Centre in New Jersey has finally embarked on a follow-up study to find out.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies