PC Blakelock trial: The long, troubled history of the Met's quest for justice

They were the less than magnificent three.

They changed their stories, had long criminal pasts and one was said to have suffered from paranoid delusions brought on by long-term heroin and alcohol abuse. Two were part of the "inner circle" of rioters who attacked PC Keith Blakelock, kicking him as he lay helpless on the ground while an attempt was made to cut off his head.

29 years later, the Crown's tainted chief prosecution witnesses - linked together by friendship or family - represented the unsteady cornerstone of the latest and ultimately unsuccessful attempt to secure a conviction for the notorious murder of a policeman during riots on Tottenham's Broadwater Farm Estate.

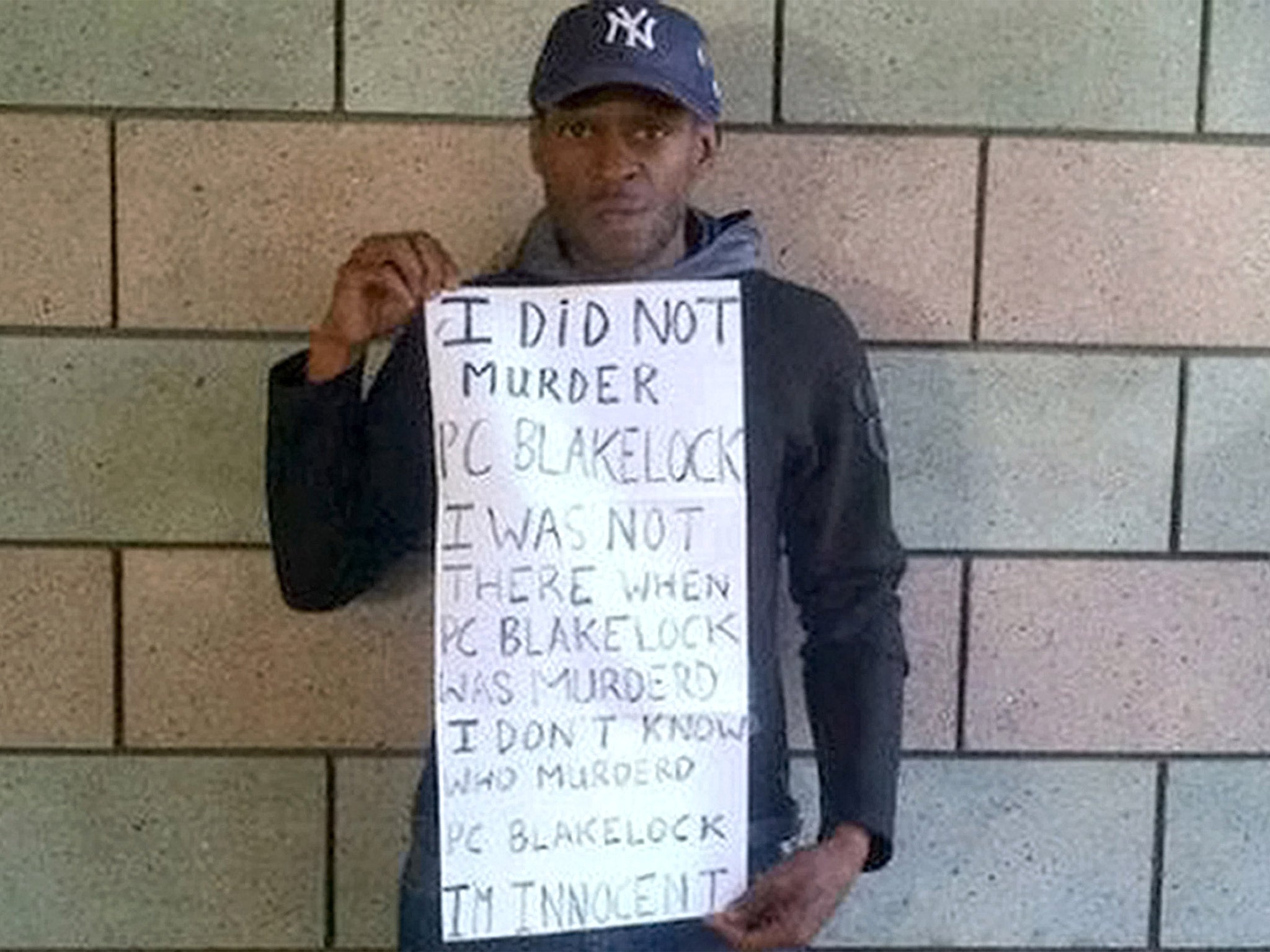

Following yesterday's acquittal of Nicky Jacobs, 45, Scotland Yard said last night that it had not given up on bringing his killers to justice. But after three investigations, millions of pounds and seven unsuccessful prosecutions, the bald fact remains that nobody has been brought to justice for a murder notable for its savagery.

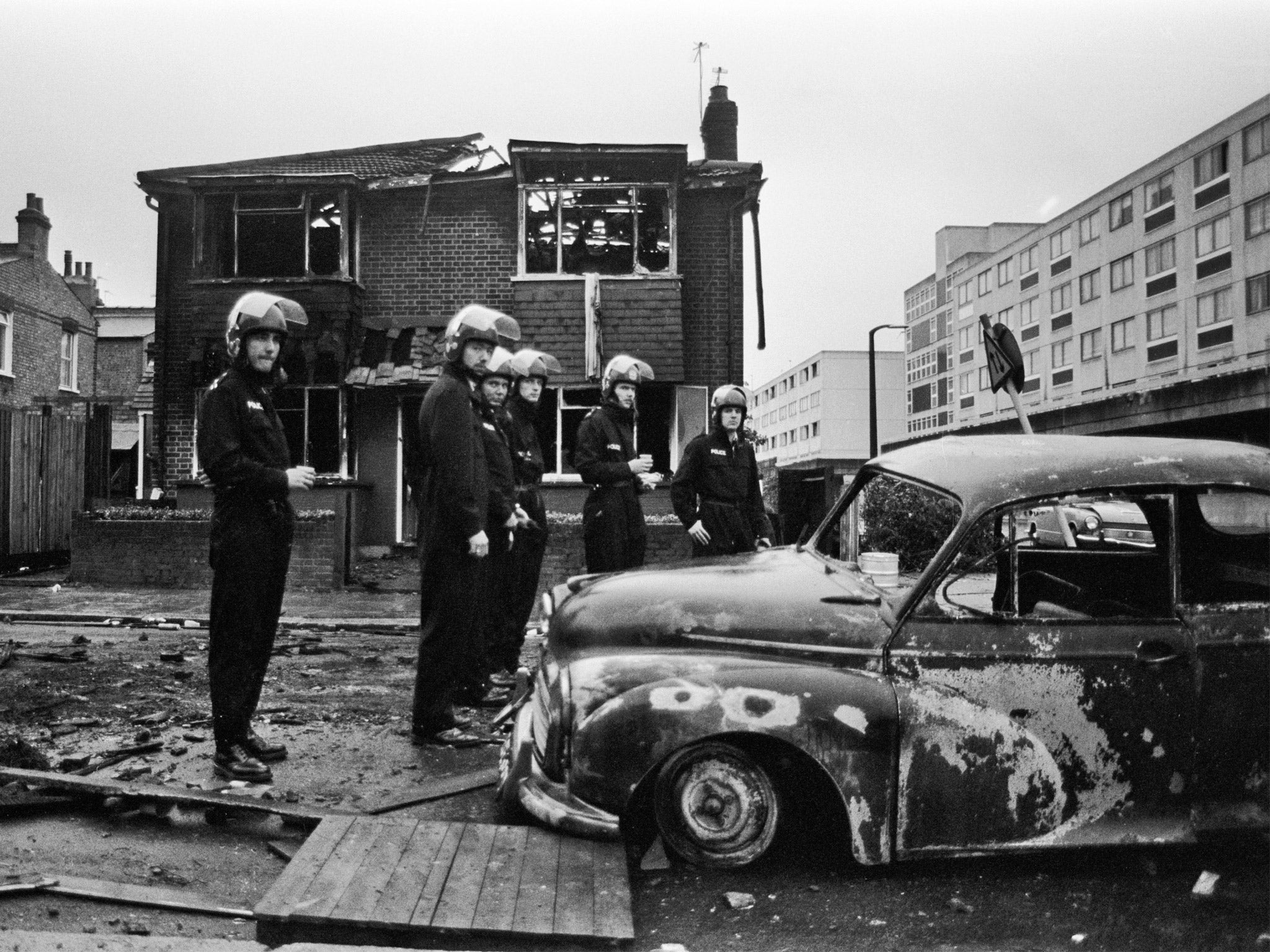

PC Blakelock, 40, was part of a group of 11 officers sent into the centre of a riot on the estate to protect a group of firefighters dousing flames on the estate on 6 October 1985. Simmering tensions between police and the black community had boiled over following the death the previous day of Cynthia Jarrett from a heart attack during a police search at her home.

PC Blakelock became separated from his colleagues and fell during a retreat under attack from rioters. He was surrounded by a group that hacked at his body shouting "kill, kill, kill the pig" and "get his f***ing head on a pole". As the group of attackers fell back, his body was left with more than 40 wounds.

His murder was followed by three extraordinary police investigations. The first, headed by Det Chief Supt Graham Melvin, resulted in the prosecution of three youths, and three men. But the tactics were described in court as having more in "common with a witchhunt of the 17th century than an orthodox attempt to solve a murder" after youths were questioned without legal representatives.

Without forensic evidence or CCTV pictures, it relied on confessions and witness statements. "You ain't got enough evidence," one of the accused and the alleged ringleader, Winston Silcott, was alleged to have told the senior officer during an interview. "Those kids will never go to court. You wait and see. No one else will talk to you. You can't keep me away from them."

Mr Silcott, Mark Braithwaite and Engin Raghip were convicted of murder but scientific tests later revealed that the notes from the key interview with Mr Silcott - which were not routinely recorded - had been tampered with. Based on the findings, the so-called "Tottenham Three" were cleared in 1991, reigniting feelings of resentment and mistrust between the police and the black community.

A second innovative murder inquiry, headed by Commander Perry Nove from an outside force the following year, offered lifetime immunity to witnesses who were "kickers" in the attack rather than "stabbers" if they cooperated with police. Officers traced witnesses using covert methods, including messages left on car windscreens. Police funded solicitors to represent the victims in an attempt to build bridges with the community. Interviews were videotaped to prevent anyone from being fitted up, a dramatic development for the time.

Two witnesses - known only by their pseudonyms as John Brown and Rhodes Levin - said they had seen Nicky Jacobs among the attackers. Further evidence against Nicky Jacobs included a rap poem discovered by a prison officer in his cell where he was serving six years for affray over the Broadwater Farm riots. The author of the rap wrote that he had a chopper and "me have an intention to kill a police officer PC Blakelock de unlucky f***er".

But despite the evidence, the Nove inquiry did not lead to anyone being charged over the killing on the advice of a senior barrister. The inquiry ended when Det Chief Supt Melvin and another senior investigator, Det Insp Maxwell Dingle, were put on trial for allegedly tampering with a witness statement. They were cleared by a jury.

Some of the witnesses, including Rhodes and Brown, were paid for their willingness to help the police. In the case of Brown, who was struggling with debts and late rent, he received £5,000 in payments and loans. Further payments for expenses were paid to the men as part of a witness protection scheme.

The inquiry was set aside for five years until a renewed convulsion in the history of the Metropolitan Police. Battered by criticisms over its failure to solve the murder of Stephen Lawrence and damned with the label of institutional racism, the force pledged to review outstanding unsolved murder cases.

In 1999, the late officer's widow, Elizabeth, wrote to the head of Scotland Yard, Sir Paul Condon, to ask what he planned to do about her late husband's case. It sparked a wide-ranging review and the reopening of the inquiry in 2003 under Det Supt John Sweeney. The task was enormous. Officers trawled through nearly 75,000 documents and nearly 18,000 people were listed on the investigation database. Every time police spoke to a potential witness, they carried out a risk assessment to ensure they were not targeted as a police informant.

"It would have been nice to have lots of witnesses of perfect character, but unfortunately... you don't tend to get that in the middle of a riot," said Scotland Yard Assistant Commissioner Mark Rowley. The dead man's clothing was retrieved and modern forensic techniques were used on the clothing and the knife found embedded in his neck, but it was unable to provide much information. Some of the men previously accused of murder, including Winston Silcott, were contacted by the inquiry team, but declined to respond.

Six men were referred to the Crown Prosecution Service for possible charges. They included some previously accused of the murder and were considered for retrial under the amendment to the law of double jeopardy, which can allow a person to stand trial twice for the same crime.

Prosecutors considered there was only enough evidence to charge Mr Jacobs. They assessed new evidence including the arrest in 2000 of Mr Jacobs - an unsuccessful career burglar - after he was caught by members of public, who promptly sat on him until the police arrived. When they did, Mr Jacobs was said to have told the arresting officer: "Fuck off, I was one of them who killed PC Blakelock," the trial was told.

They also had a third witness, Q, who came forward after an approach by police in 2009. He had maintained that he had seen the murder from his flat on the estate, but inconsistencies in his evidence prompted the jury to ask if he was suffering from Korsakoff's Syndrome, an alcohol-linked condition that can lead to a person inventing events to fill gaps in memory. Q's evidence to the trial was flawed: he told the court that he first discussed the case with officers in 2009. However, the court heard that he had spoken with police on two occasions during house-to-house inquiries within a fortnight of the murder. He signed a document suggesting that he had "stayed at home and saw nothing".

The extent of the problems linked to the witnesses came through logs that ran to hundreds of pages detailed their convictions, addictions, substance abuse and psychiatric matters along with their changes of story. Scared of reprisals, the three witnesses gave evidence from behind a black curtain and their voices digitally altered to try to disguise their identities. Their real names were described as the "worst kept secret" on Broadwater Farm, despite their names not appearing on an anonymously posted "snitch list" that circulated the estate four years ago.