The Big Question: Does fear of crime reflect the reality of life on Britain's streets?

Why are we asking this now?

Jacqui Smith has admitted she would not feel comfortable walking London's streets alone after dark – whether it be in deprived Hackney or affluent Chelsea.

Critics immediately pounced on the Home Secretary's confession as "an admission of failure" and pointed out that millions of shift-workers without the luxury of a bodyguard have to travel late at night.

Efforts by her aides to undo the damage only made things worse when they claimed she had recently bought a kebab in Peckham, south-east London, at night. It later transpired her trip to the takeaway took place in the early evening and in the company of a minder.

At a time when the Government repeatedly trumpets its successes in reducing crime, her ill-chosen comments inadvertently echoed the fears of voters. Last year, 46 per cent of Londoners said they did not feel safe in their neighbourhoods at night.

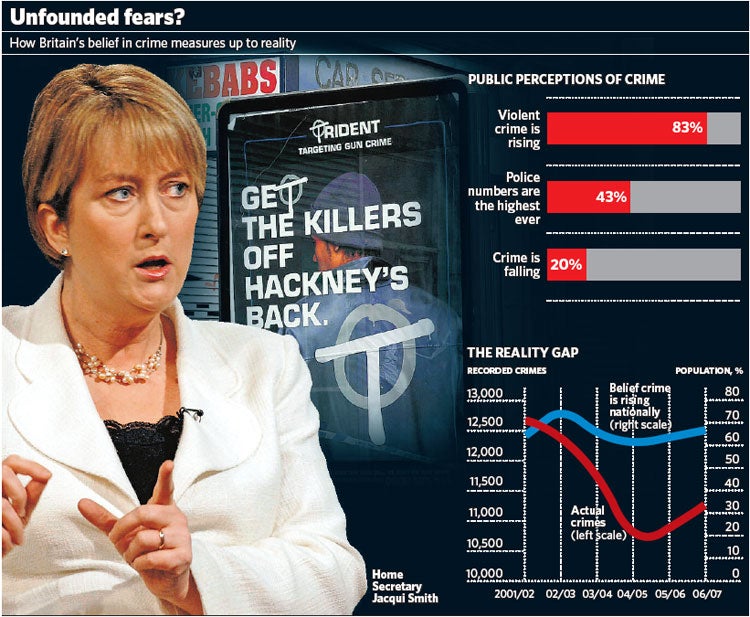

Whatever the official figures might say, the public simply do not believe that levels of crime – and in particular violence – are falling. Ministers are now placing a higher-priority in tackling the fear of crime, which is higher than in most of Britain's European neighbours.

Are the streets more dangerous?

According to the British Crime Survey (BCS), which is far from perfect, but is still the most authoritative measure of offending levels, the answer is an unambiguous no.

All crime is down by 32 per cent over the last decade, with even bigger falls in burglary (55 per cent) and vehicle thefts (52 per cent), leaving the public judged to be at a 24 per cent risk of being a victim of any form of crime in a year, the lowest figure since the survey began in 1981.

The BCS also shows a sharp fall in violent crime of more than 40 per cent from its peak in 1995 and of 34 per cent since 1997. Rapid declines in the late 1990s have been replaced by a more stable pattern since the start of the decade, with the risk of falling victim to a violent crime in a year estimated at 3.6 per cent.

Beneath the reassuring headline figures, though, there are some rather more disconcerting statistics.

Last year, 9,608 firearm offences were recorded by police in England and Wales (more than a half of them in London, Greater Manchester and the West Midlands) – almost double the number eight years earlier. Knife crime also appears to be on the up, with an estimated 148,000 offences last year, an increase of 28 per cent over a decade.

Does the public believe crime is falling?

Quite the reverse. The BCS last year found nearly two-thirds of people thought crime was increasing in Britain. Asked, however, if they though it was rising in their local area, the proportion fell to 41 per cent.

Research for Ipsos Mori in 2005 found only 20 per cent of the public believed that crime was dropping. Last year, 55 per cent told the same pollsters that law and order was among the most important problems facing the country, well ahead of the next highest issue. It is a bigger cause for concern for Britons than the citizens of any equivalent western European nation, and even the United States.

So why the gap between reality and perception?

The Government has no control over the everyday experience of crime, or the anecdotes people hear of neighbours, friends and colleagues falling victim to thieves and muggers.

Moreover, smashed bus shelter windows, groups of vaguely menacing teenagers gathering in market squares or graffiti appearing overnight on public buildings will never be recorded as crimes, but play into a wider feeling among the public that levels of law and order are declining.

Ministers and some criminologists also believe that the reporting of crime, both nationally and locally, inevitably skews the public's perception of their vulnerability. Asked by Ipsos Mori last year why they believed crime had risen, 57 per cent of the public said from watching television and 48 per cent said from reading newspapers.

Home Office officials frequently protest wearily that journalists inevitably light upon the black spots in sets of crime statistics that are broadly positive.

Mike Gough, professor of criminal policy at criminal policy, Kings College, London, wrote recently: "Media portrayals of crime and justice do seem to be particularly perverse.

"News stories about soaring crime and judges who are soft on crime and soft in the head are good for circulation, but bad for justice – when the headlines bear so little relation to reality."

Can it all be the media's fault?

There is a school of thought that the Government is the author of its own downfall over crime, that ministers' hyperactivity over law and order, with a succession of criminal justice bills and the creation of more than 3,000 new offences in a decade, is fuelling public anxiety. Weekend headlines foreshadowing the installation of metal detectors in inner-city schools, and the promise of a fresh government crackdown on knife crime in the New Year will not have reassured the public that things are getting better.

Diane Abbott, the Labour MP for Hackney North and Stoke Newington, made the same point, accusing Ms Smith of "feeding a culture of fear" with her comments. She said: "Jacqui needs to get to know inner-city London. She will find it is not the nightmarish scene from a Hogarth engraving that she seems to imagine."

Enver Solomon, deputy director of the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies in London, said the "increasing general anxiety" among the public over many aspects of their lives inevitably heightened the fear of crime. He said: "The biggest threat to children is from road deaths, but they might perceive that 'stranger danger' is the most likely way of their children being killed."

How are ministers trying to tackle fear of crime?

Ms Smith admitted at the weekend that the Government had a "big job" to persuade people urban areas had not become more dangerous. "I understand that whilst it's a fact that crime is falling, what you want to know is what's happening on your street; what the police officers in your area are doing and who they are. That's one thing we'll provide to people. Serious violence is something we need to address."

Part of her solution will be a fresh drive to build links between police and communities and devolve responsibility for policing to the most local possible levels. Louise Casey, the Government's former "respect tsar", has also been appointed to head a Whitehall review of how communities be better engaged in the fight against crime. In other words, Ministers hope that when communities see crime on the retreat locally they will be convinced that national tragedies are tragic aberrations rather than symptomatic of a slow slide into chaos.

Is Jacqui Smith right to be worried?

Yes...

* Levels of violent attack are on the increase in some parts of the country

* Gun and knife crime is on the rise, and more teenagers are now joining gangs

* Binge-drinking afflicts many city centres, and in some it regularly spills over into violence

No...

* Figures show that overall violent crime has been falling for more than a decade

* The chances of falling victim to a violent attack are estimated to be 3.6 per cent

* Acts of violence are rare in the vast majority of communities – even at night

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks