‘I helped defeat the Nazis in 1941, and I'm ready to fight fascism again in 2017’

Aged 18, Betty Webb gave up a domestic science course and joined the anti-Nazi codebreaking operation at Bletchley Park. Now aged 94, she recalls the first defeat of fascism - and reveals how she is helping to crush it again

Before she makes your coffee, Betty Webb feels obliged to apologise for having been unavailable the day before.

“There was a conference of the Birmingham branch of the Women’s Royal Army Corps Association, of which I am chairman, so I thought I should attend. They asked me to stay on as chairman yesterday. I said yes.”

Not bad, perhaps, for a 94-year-old on her second hip replacement. But it wasn’t bad either, as an 18-year-old in 1941, to have left a domestic science course to join the fight against fascism.

As part of the top secret codebreaking operation at Bletchley Park that cracked the Enigma cipher and let the British read Nazi messages, Mrs Webb was involved in an intelligence triumph said by historians to have shortened the Second World War by between two and four years.

Two years ago, she learned from a researcher that those soon-to-be-decoded messages she had been ordered to catalogue – strings of letters and numbers that meant nothing to her at the time – had in fact been communications between the worst of the worst: members of the SS and the Gestapo, some of them discussing the beginnings of the Holocaust.

Once the chill of the revelation had subsided, she says, “I was rather pleased to know I had been working on an important part of the exercise. I do hope I made a contribution.”

Mrs Webb quite understands the interest in Bletchley. She’s just amazed anyone would want to come here, to her cosy front room in a Worcestershire village, where she keeps the binoculars on the windowsill, ready to examine whatever birds she may spot in the garden.

“I’m quite surprised people are interested in me,” she says.

You try to tell her she played a key part in defeating fascism, but are very politely reminded: “Well yes, as one of 8,000: very young, very inexperienced, only doing what I was told to do.”

She greets nearly every question with a rather enigmatic, not to say mischievous grin.

As far as you can tell, the grin seems to come from her own lively curiosity about the interviewer, wry amusement at the younger generation, and a good dollop of kindly encouragement.

It does seem that Mrs Webb was fairly typical of many of the 8,000 women who found their way to Bletchley during the Second World War. (By 1945, women made up three-quarters of the workforce at ‘The Park’.)

By her own admission, she had led rather a sheltered life, growing up in Richard’s Castle, a village on the Shropshire-Herefordshire border, father a cricket-loving Lloyds Bank employee, mother a music teacher.

By May 1941 she was at Radbrook College near Shrewsbury, on a domestic science course where young ladies were taught how to cook, run a house and do household accounts.

“I remember listening to news of the war on the wireless,” she says. “Bad news, things like ‘one of our aircraft is missing’.

“We wanted to do something for the war effort, and domestic science wasn’t it.”

Besides: “The food we were learning to cook on that domestic science course was so limited, because of wartime rationing. Sausage rolls, I recall. It didn’t appeal.”

Betty Vine-Stevens – as she then was – volunteered for the Auxiliary Territorial Service.

After basic training, to her surprise, she found herself ordered to London, to an office in Piccadilly where she was interviewed by “a very pleasant, twinkly-eyed Army Major from the Intelligence Corps.”

From there she was ordered to take a train to Bletchley in Buckinghamshire, without being told why.

The mystery only deepened on her first day at Bletchley Park, where her first duty was to sign the Official Secrets Act, and to listen to an Army captain talking her and the other girls through how severely they would be punished for breaching it.

“He took his service revolver out and put it on the table. It did rather add to the atmosphere.”

“I can only assume,” adds Mrs Webb, “That the reason I was picked in the first place was because I was bilingual.”

Her genteel childhood had not been without its peculiarities.

Betty had had German and Swiss au pairs. There had also been a month-long exchange trip to Herrnhut, near Dresden, in 1937, four years after Hitler had come to power.

She may have been a naïve 14-year-old, but Betty saw no reason why she should give the classroom Heil Hitler salute that was compulsory for her German exchange and all the other girls at the school.

“What did I do?”

Trying not to laugh, Mrs Webb raises her arm and flops her hand about most irreverently.

She also remembers Christina, a Jewish schoolmate of her German exchange.

“She sort of clung to me. It was only years later that I realised she might have been trying to get out of Nazi Germany by making a friend of me.”

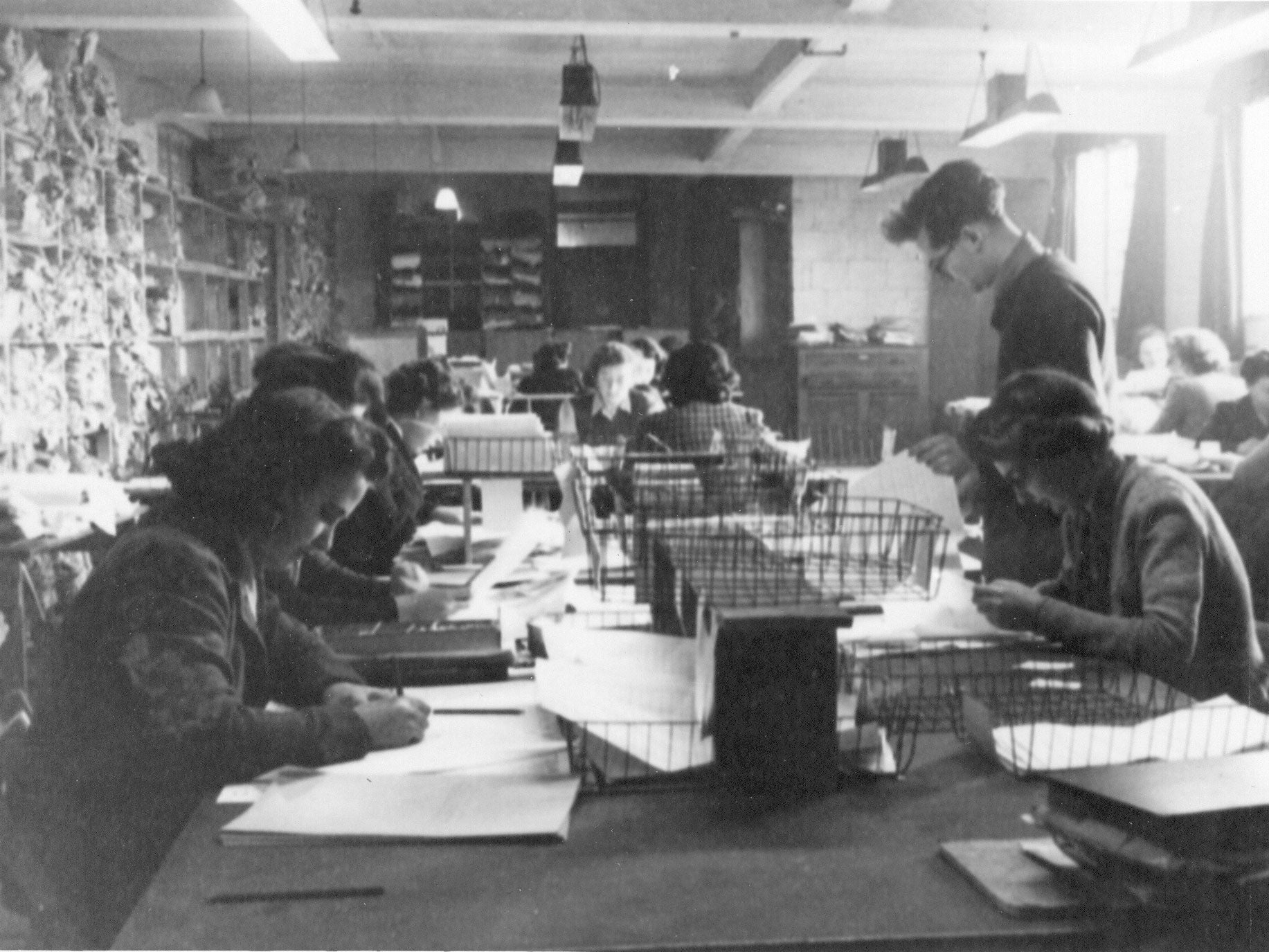

Four years later, Betty was in Bletchley Park Mansion, in small rooms above the ballroom, under the command of Major Ralph Tester, handling coded SS and Gestapo messages.

In 1943 she moved to Block F, to paraphrase decoded Japanese messages. (The paraphrasing was a precaution, so if the Japanese picked up any subsequent British messages, it would not be obvious to them that their codes had been cracked.)

Such was the strength of Bletchley’s secrecy culture that it became instinct for Mrs Webb to dismiss the precise content of the messages from her memory. They were about troop movements, she thinks.

“To us then,” she says, “Kohima was just a name.”

To historians now, Kohima is “the Stalingrad of the Far East” – the brutal battle that in 1944 finally turned the tide against the Japanese in the Burma campaign.

Mrs Webb thinks about it for a moment.

“I just hope my work did some good.”

Like everyone else who had served at Bletchley Park, she kept her secret, insisting her war had featured nothing more than “boring secretarial work”, until 1975, when the operation was finally allowed to be made public.

Then, in her eighties, long released from her duty of secrecy, she wrote a book about her part in defeating fascism.

“I realise,” she wrote, “How fortunate I am to have lived through such progressive times.”

Now, though, Mrs Webb reads the reports of white supremacists giving Nazi salutes in Donald Trump’s America, of serving British soldiers being arrested on suspicion of terror offences as part of a banned neo-Nazi group.

“Well,” she says, in tones of polite outrage, “I am disappointed, which is putting it mildly.

“I thought we had done away with the Nazis – finished, kaput – but it [fascism] is coming back. What is going on?!”

She closes her eyes in exasperation at the mention of Nazi-saluting American white supremacists.

“Horrendous. You do feel rather let down.”

But it is when she talks about the arrest of the British soldiers that – for the first and only time – her polite understatement vanishes.

The soldiers remain innocent until proven guilty, but the nature of the allegations against them and their supposed membership of the far-right group National Action have dismayed Mrs Webb.

“I am horrified,” she says, “Utterly horrified. [If they did what they are accused of] How dare they? They have joined our forces and sworn to serve the Queen, and they go and let us down like that? I’m sorry, it’s disgusting. I could never forgive them.”

By contrast, she considers peaceful anti-fascist protesters among “some very good things in this world”.

She probably won’t be waving a banner with them, though. Mrs Webb is not, she confirms – perhaps a little superfluously – the demonstrating, shouting type.

But just as she did 70-odd years ago at Bletchley Park, Mrs Webb is once again ‘doing her bit’ to defeat fascism, in quieter ways.

And yes, she insists, she most certainly is “still doing something”.

She already has an MBE, awarded in 2015 for services to remembering the work of Bletchley Park. That, though, is no excuse for thinking that aged 94 she should take a well-earned rest – especially not now, in the current climate.

“No,” she says. “I don’t intend to down tools yet. I am still giving talks on Bletchley. I am still fit enough to spread the word about Bletchley, about the whole exercise, about what we were fighting.

“By and large, I suppose it’s academic interest, but on the other hand, for some youngsters, it might be giving them the right attitude: opposing fascism, not promoting a form of Nazism.”

“I’m afraid it’s a rather uncertain world,” adds Mrs Webb. “We mustn’t be complacent. You have got to be so very careful in backing the right attitude, and this all comes back to education, and pointing out how dreadful things like fascism and the Holocaust are.

“Which I’m still doing. Hopefully.”

She is, of course, also still on the parish council, where she has served since 1987:

“It’s important to feel one is giving …”

After the photographs have been taken, when the chat turns to her love of birdwatching, Mrs Webb produces one of the nature notebooks that she and her sister kept as children, the cover emblazoned with the motto of the Parents’ National Educational Union.

“That’s our motto,” explains the 94-year-old. “I am, I can, I ought, I will.”

It seems to explain a lot.

As for Bletchley Park and defeating 1940s fascism: “I was just in the right place at the right time, one of those fortunate enough to be a member of the team.”

She grins yet again. “I never did miss that domestic science course.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments