From the East India Company to Procol Harum: the end of justice in the Lords

Today, the law lords move out to the new Supreme Court. Andy McSmith traces the colourful history of ermine-clad justice

Today, for the last time, a little group of men and women will sit together on the long red benches of the House of Lords, and mumble. The absence of drama or oratory, the plain way that they dress, their low, barely audible voices, and the long rows of empty seats around them might give someone walking in by mistake the idea that nothing very important is happening. But, actually, this is history.

It is the last day that the centuries-old House of Lords can call itself the nation's final dispenser of justice. As part of its slow battle to reform the Lords and the judiciary, the Labour Government passed a law in 2005 to create a new Supreme Court.

After a long delay and much controversy, the court has a new building, on the west side of Parliament Square, facing the Commons, and, after the summer break, the country's 12 most senior judges will reassemble, not as law lords, but as Justices of the Supreme Court.

The image most of us have of law lords is of elderly men decked in gorgeous red ermine who have been around, well, almost as long as Time Lords. Actually, compared with other aspects of Britain's archaic constitution, law lords have been and gone in the twinkling of an eye.

William Gladstone proposed a Supreme Court in 1873. The Conservatives opposed him, and when Benjamin Disraeli was returned as Prime Minister, his government put through the Appellate Jurisdiction Act of 1876, creating the Lords of Appeal in Ordinary, to give the law lords their correct title.

But the House of Lords has been hearing cases for much longer than that. They acted as a law court in the the Middle Ages, although, of course, the final court of appeal back then was the king. When the king's authority collapsed, in Oliver Cromwell's day, there were stand-offs between the two houses of Parliament over which was the ultimate legal authority.

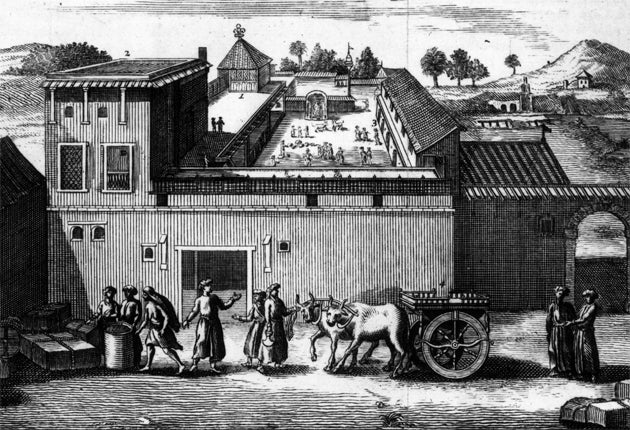

In 1657, a merchant named Thomas Skinner fitted out a vessel and sailed east in hope of making some money, using an island off India that he had bought from the local monarch as his base. But the East India Company reckoned he was poaching on their territory, seized his ship, his home, and his island, and made him take the long journey home overland. The Lords awarded him £5,000 damages, but the East India Company refused to accept their jurisdiction and appealed to the Commons, who had Skinner locked up in the Tower of London. Round one to the MPs.

A few years later, after the Stuarts had been restored to the throne, two wealthy neighbours from Wiston, in Essex, became involved in a bitter land dispute. Sir Thomas Shirley had been a monarchist. He claimed to have suffered discrimination during Cromwell's time, and that land which had once been his family's was now occupied by the local MP, Sir John Fagg. Sir Thomas appealed to the Lords, whereupon Sir John retorted that the Lords could not possibly sit in judgment on an MP. The Commons backed him at first, threatening Sir Thomas and anyone who sided with him with dire penalties, but eventually backed down. After that, there was no longer any dispute that the Lords was the ultimate authority in civil cases.

The last two cases the law lords will hear today involve Africans appealing against deportation. They will also deliver judgments pending on seven cases they have already, including an appeal by Debbie Purdy, a multiple sclerosis victim from Bradford, who wants a ruling that her husband will not be prosecuted if he helps her to go to a Swiss clinic to commit assisted suicide.

Another judgment involves something that seems to belong to an age long gone, just like the law lords. Matthew Fisher, who played the organ on "A Whiter Shade of Pale", a mega hit for the group Procol Harum during the summer of love, in 1967, is suing the group's singer and frontman, Gary Brooker, for a share of the royalties. The question of who wrote the whining organ intro on that old classic will be settled today.

But not by men and women dressed in ermine. The reason we picture law lords bedecked in robes is that the occasion on which they are most visible is the annual opening of Parliament by the Queen, when they all dress up in their finery and sit on the benches for peers who do not belong to any political party. At work, judging cases, they dress like office workers. Only the clerk has a ceremonial wig.

The Government decided to move them out of the Lords to make the separation between politics and the law clear and visible, though many people thought the break with tradition was unnecessary.

Earl Ferrers, one of the last hereditary peers in the Lords, was particularly scathing. "It is said that people do not understand the difference between a political lord and a law lord and, therefore, they should be housed separately. However, not many people know how to butcher a pig. That does not really matter because, fortunately, a butcher does."

The Earl speaks with authority, because a member of his family was the defendant in one of the most famous cases tried by the Lords. The fourth Earl Ferrers was charged in 1760 with murdering one of his servants, and despite his plea of insanity, his fellow peers convicted him, and he was hanged.

New look for justice: The Supreme Court

* One of the many new features of the Supreme Court, which will open for business on 1 October, is that it will be the first court in Britain with inbuilt facilities for broadcasting.

* Preparing the Grade II listed building, which used to be the courts of the Middlesex Guildhall, cost nearly £60m. Running costs are expected to be around £1.2m, causing people to ask whether it is worth it.

* It is a far more impressive setting than the committee rooms of the House of Lords, where the law lords, pictured right, have dispensed justice, their costs absorbed in the general running of the Palace of Westminster.

* The new court's original address was Little George Street, Westminster, but the law lords complained that it was not grand enough, so the address was changed to Parliament Square.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments