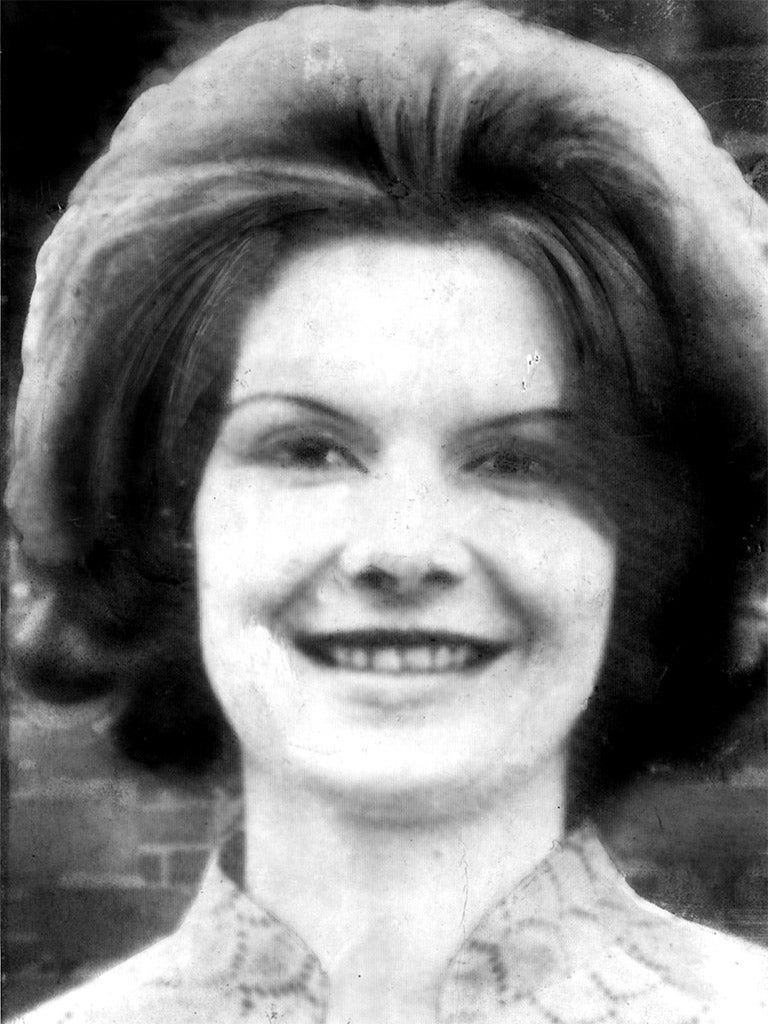

Lady Lucan is dead – but what happened to her husband Lord Lucan?

Since disappearing after killing the family nanny in 1974, Lord Lucan has been 'seen' everywhere from Ireland to Botswana, to living in a Land Rover with a pet possum in New Zealand. His widow, who died on Tuesday, always insisted he was dead

Whatever secrets she had, if indeed there were any, Lady Lucan took them to her grave.

Aged 80, she was declared dead – in unexplained but unsuspicious circumstances – after being found on Tuesday in the Belgravia mews cottage that, as their marriage crumbled, had once served as a temporary home for her husband, John Bingham (Lord Lucan).

For 40 years, Veronica (Dowager Countess of Lucan) lived in a property associated with a husband who had nearly killed her, who had vanished after murdering the family nanny in the mistaken belief he was killing his wife.

She was one of the last people to see Lord Lucan alive.

She escaped from him – despite him bludgeoning her with lead piping, moments after he killed 29-year-old nanny Sandra Rivett in the darkened basement of the family home, on the night of Thursday 7 November 1974.

Despite all insistences to the contrary, some remained convinced that she must have had an inkling of the true fate of Lord Lucan after he disappeared.

In photographs for one of her last interviews, the Dowager Countess stared at the camera with eyes that seemed haunted.

Certainly, for nearly half a century the mysterious disappearance of her husband has haunted and – it has to be admitted – ghoulishly entertained the world with the unanswered, perhaps never-to-be-answered question: where is Lord Lucan?

Over the course of 43 years, the fugitive seventh Earl of Lucan has been ‘spotted’ everywhere from Ireland to Australia.

He has been ‘seen’ in Greece, in Botswana, in New Zealand living in a 1974 model Land Rover with his pets Snowy the cat, Camilla the goat and Redfern the possum.

Tales have been told of Lord Lucan hiding out in Africa until at least 2000, a year after the High Court declared him dead, his children being flown out so he could see them – but only from a distance, without speaking to them.

But the known facts don’t take us much beyond November 1974.

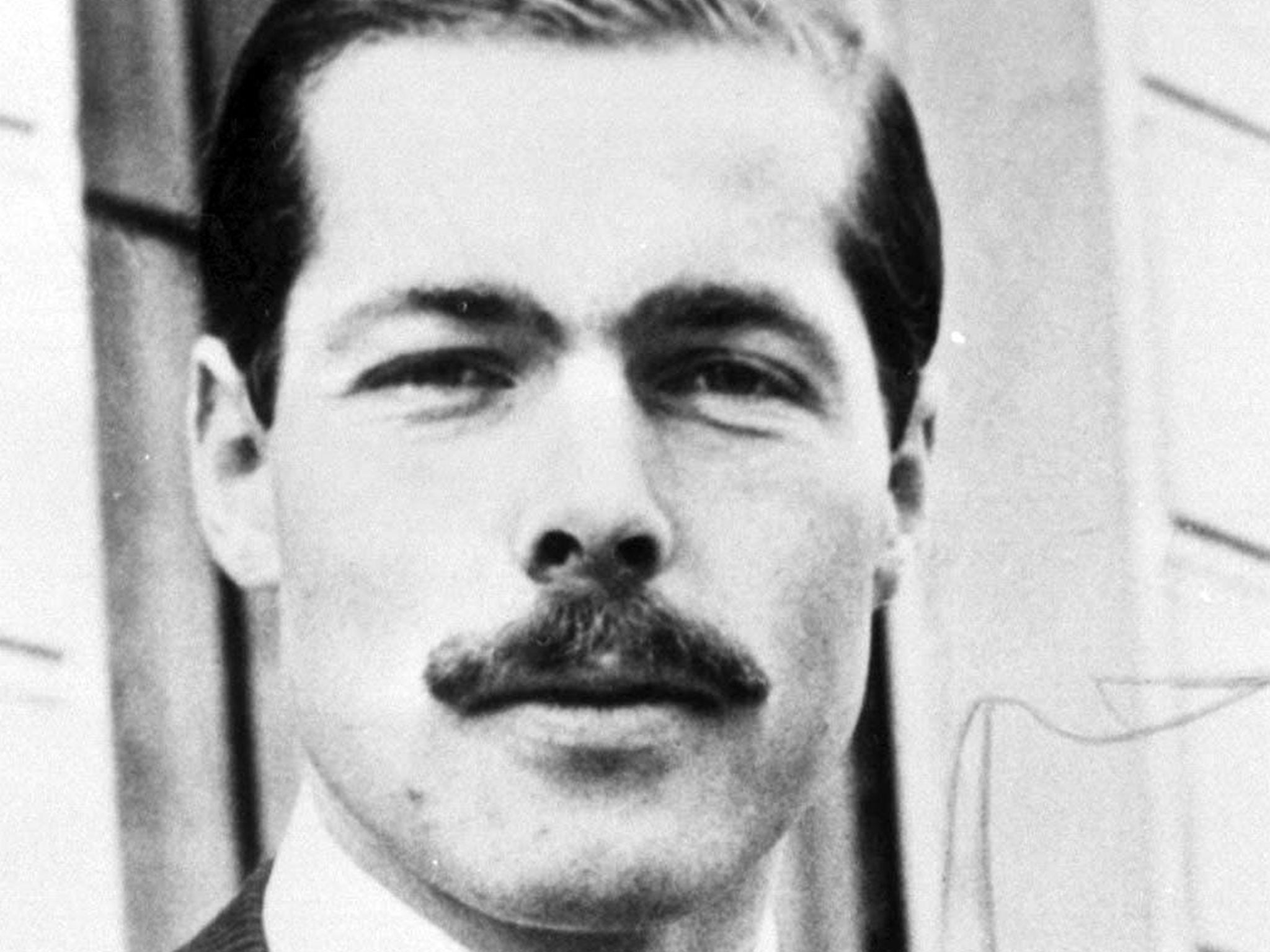

Darkly handsome, with patrician good looks of the cold, unsmiling kind, ‘Lucky’ Lucan was a gambler with unsecured debts of some £45,000.

He had split from his wife, engaging in a bitter divorce battle and, some said, becoming obsessed with regaining custody of his three children.

On the night of 7 November 1974, Lucan had gone to the five-storey family home at 46 Lower Belgrave Street, London.

In the unlit basement kitchen, detectives later said, he encountered Ms Rivett. She had gone downstairs to make tea for Lady Lucan, who was watching television in her first-floor bedroom.

In the dark basement, it is assumed, Lord Lucan mistook Ms Rivett for his wife. He bludgeoned the nanny to death with a length of bandaged lead piping – or so most people believe.

Lady Lucan walked downstairs to see why it was taking the nanny so long to make a cup of tea.

There, she said, she encountered Lord Lucan, who attacked her near the top of the basement stairs, hitting her over the head with the piping as he grappled with her.

She managed to escape, it is said, after stopping him in his tracks by squeezing his testicles.

“[Our children] George and Camilla were seven and three when it happened,” she later recounted, “and asleep in bed.”

Lady Lucan ran for help at the pub down the road, reportedly entering the Plumbers Arms covered in blood and saying: “I think my neck has been broken. He tried to strangle me.”

Lord Lucan was able to drive 42 miles to the home of Susan Maxwell-Scott, a friend who lived with her husband in Uckfield, Sussex.

Mrs Maxwell-Scott would later say she didn’t call the police, because she was unaware that Lord Lucan was now wanted for murder. He told her he had spotted a man attacking his wife while passing the family home, and after he intervened to save her, she accused him of having hired a hitman to kill her.

He planned to “lie doggo” for a bit, he told Mrs Maxwell-Scott.

At 1.15am on 8 November, Lord Lucan was seen driving from the Maxwell-Scott home. On Sunday 10 November, the car was found abandoned in the port town of Newhaven – a section of bandaged lead piping in the boot.

Lord Lucan had vanished, leaving behind an irresistible pall of intrigue. He became, in absentia, the last person in Britain to be declared a murderer by an inquest jury.

As Scotland Yard and Fleet Street’s finest battled to find him, they encountered what one described as the “condescending, almost patronising attitude” of the “nob squad”: the set of upper crust habitués of John Aspinall’s Mayfair casino, the Clermont Club.

Rumours have abounded about what the Clermont Set did or didn’t do to protect their chum ‘Lucky’ Lucan.

When the artist Dominic Elwes broke ranks to talk to the press, he found himself blackballed by Clermont Club members. In 1975, when Elwes took his own life aged 44, there were claims he had been hounded to death by some of Lucan’s more vicious gambling cronies.

Such claims have never been substantiated – but they have certainly helped keep the Lucan story going.

Lord Lucan ‘sightings’ now number more than 70. And counting Only last month The Independent was being contacted from Slovenia, with promises of another Lucan tip.

When confronted by a new “sighting” in yet another exotic location, Lady Lucan would invariably dismiss it as nonsense.

“He was not the sort of Englishman to cope abroad,” she once explained. “He likes England, he couldn’t speak foreign languages and he preferred English food.”

Her own theory was that Lord Lucan threw himself under the propellers of a Newhaven-Dieppe cross-Channel ferry.

In June Lady Lucan, who believed children of the aristocracy should be brought up “to behave honourably”, told an ITV documentary: “I would say he got on the ferry and jumped off in the middle of the Channel in the way of the propellers, so that his remains wouldn’t be found – quite brave, I think.”

She maintained that as a keen powerboat racer, Lord Lucan had such detailed knowledge of propellers he would have known precisely where to jump to ensure his remains were chopped up and destroyed.

A similar, but different theory was espoused many years after the event by James Wilson, one of the Clermont set.

“On discovering he’d killed the nanny,” Mr Wilson told The Telegraph in 2015, “he would have been wracked by guilt and remorse. I believe he parked his car at Newhaven, where he had a boat, weighed himself down and jumped over the side.”

There may have been honourable remorse about killing the nanny, but not necessarily about attacking the wife.

“I’m afraid Veronica wasn’t very well liked,” confided Mr Wilson. “People would have understood why he wanted rid of her.”

Others, though, have suggested a far less prosaic end.

Unconfirmed reports suggest Lady Osborne, grandmother of Evening Standard editor and ex-Chancellor George Osborne, greeted police investigating Lord Lucan’s disappearance with the comment: “The last I heard of him, he was being fed to the tigers at my son’s zoo.”

John Aspinall, Lady Osborne’s son by her first marriage, owned not only a casino but also a zoo – Howletts, in Kent.

One of the Clermont set would later claim that shortly after the murder, Lord Lucan and some of his gambling pals met at Howletts.

Lucan’s friends are supposed to have told him that, given what he had just done, his wife would inevitably get custody of the children, and also the family trust money.

But if he were to disappear, without a body to prove he was dead, probate could not legally be granted on his estate for at least seven years.

Once those seven years had passed, his children would be just old enough to take control of their own affairs, and the trust money.

Therefore, the meeting agreed, Lord Lucan needed to vanish. But how?

The friends seemingly agreed with his wife’s assessment that Lucan could not cope with fleeing abroad and eating non-English food for the rest of his days.

Instead, the story goes, Lord Lucan was left alone in a room with a revolver. Then his body was fed to a tiger named Zorra.

It is a good story, but it’s also possible that Lady Osborne – and others – had an inventive sense of humour.

It is also said that John Aspinall told police investigating the tiger theory: “My tigers are only fed the choicest cuts – do you really think they’re going to eat stringy old Lucky?”

Regardless of whether or not he ended up inside a tiger or at the bottom of the Channel, Lord Lucan has lived on in the public imagination, and sometimes in public mistakes.

On Christmas Eve 1974, nearly three months after the disappearance, Australian police arrested a man in Melbourne thinking they had caught Lord Lucan.

In fact, they had caught John Stonehouse, the former government minister and Labour MP – who two years earlier had, in tabloid parlance, ‘done a Reggie Perrin’: faked his own death from drowning by leaving a pile of his clothes on a Florida beach.

In 2007, people in the rural town of Marton, New Zealand, were reportedly convinced they had found Lord Lucan.

They claimed one Roger Woodgate was in fact the fugitive earl. He had, they said, come to New Zealand in 1974, the same year that Lord Lucan disappeared.

He had an upper-class English accent and a military bearing, they said. He had a moustache.

Lord Lucan was an Eton-educated aristocrat with a record of service in the Coldstream Guards. And a moustache.

Lord Lucan, the locals said, was now living rough in a Land Rover – 1974 model – with his pet cat, goat and possum.

A bemused Mr Woodgate insisted he had been the victim of troublemaking gossip, sparked by a feud with some neighbours.

“I’m not Lord Lucan,” said the unemployed ex-pat. He was 10 years younger than the real earl, “and five inches shorter”.

At least Mr Woodgate was alive to issue a denial.

In 2003 The Sunday Telegraph’s front page carried sensational news. An ex-Scotland Yard policeman had apparently discovered that Lord Lucan had been living in a beach shack in Goa from 1975 until his death in 1996.

The ex-copper had found a grainy photo of a shaggy bearded man known to backpackers as ‘Jungly Barry’.

“Is this Lord Lucan?” asked The Sunday Telegraph.

“Er, no,” replied Monday’s Guardian. “It’s Barry the banjo player from St Helens.”

Barry Halpin had been a folk singer, frequenting pubs and clubs in 1960s North-west England – but never the Clermont Club in Mayfair.

Or as Lady Lucan put it when shown the Jungly Barry photo: “I could never imagine my husband looking so pathetic.”

She was equally imperious when discussing the whole Lord Lucan circus. “It’s unutterably boring,” she said.

“No informed people believe the seventh Earl to be alive,” declared the “official website of the Countess of Lucan”, in a post written years before her death. “I have publicly stated since 1987 that my late husband is not alive, and I sometimes use the prefix ‘Dowager’ to make my position clear which is that of a widow.”

In truth, if the Dowager Countess of Lucan appeared haunted, she had much to be haunted by.

The attack by her husband and the murder of Sandra Rivett were only part of it. She had, she said, been beaten and belittled by her husband for much of their marriage.

He would beat her with a cane, she said earlier this year. “He must have got pleasure out of it because he had intercourse (with me) afterwards.”

She had suffered from mental illness and lost custody of her children in 1983, becoming estranged from them for decades. She had five grandchildren, she told an interviewer, and she hadn’t met any of them.

But as she reflected on her life in June, three months before her death, she insisted she wasn’t lonely.

“I don’t feel so now,” she said, “although I was lonely in my marriage.”

The widow of murdering Earl Lord Lucan added: “All my relationships were cold.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments