Slavery: How women's key role in abolition has yet to receive the attention it deserves

The names of abolition's heroines have been all but wiped from memory

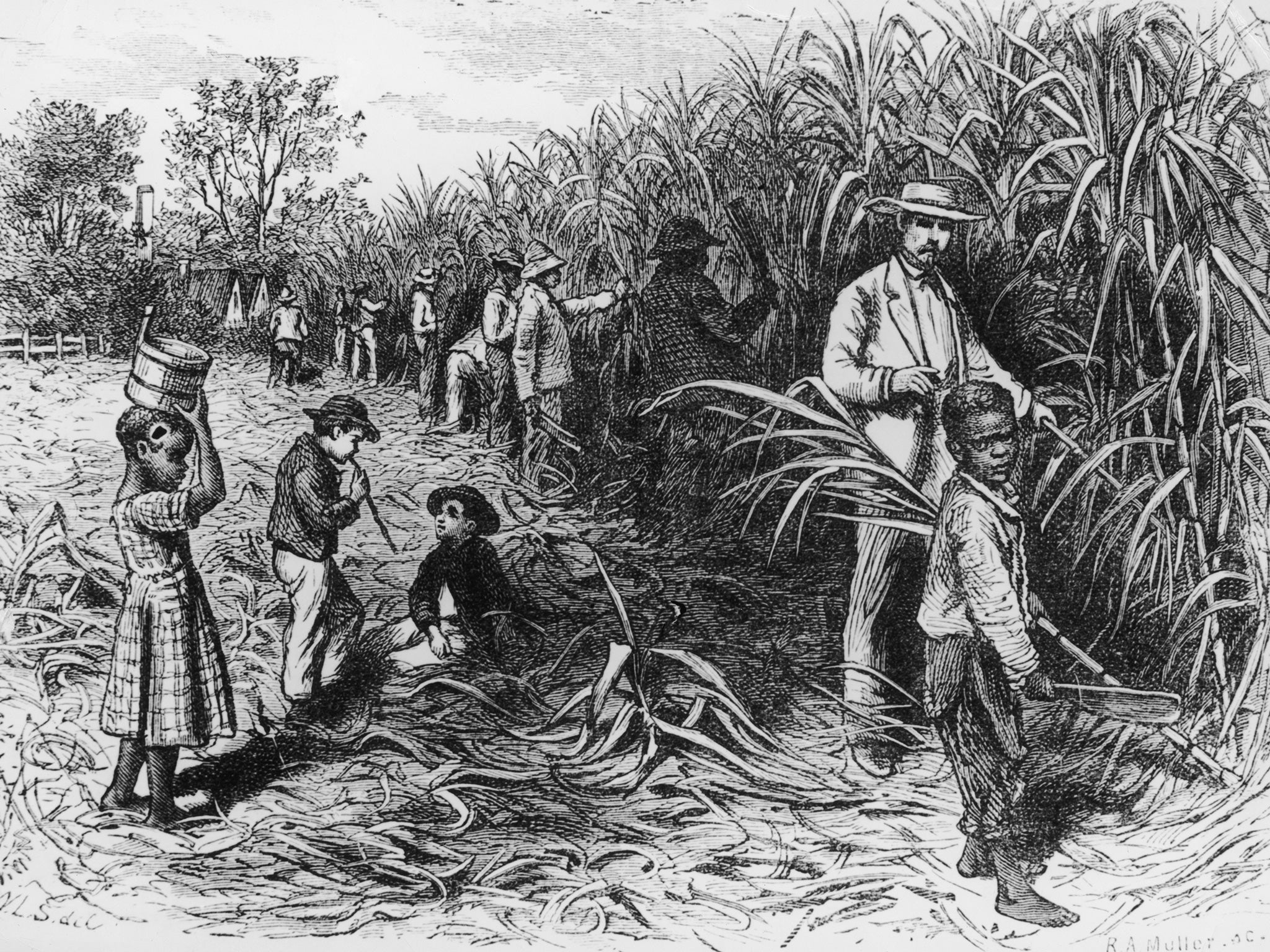

The journey of Mary Prince from the salt ponds of Bermuda to a cause célèbre in early 19th-century Britain came at unbearable personal cost. Torn from her family in a slave auction and routinely beaten while naked, she was brought to England by her owners after years of brutality on Caribbean plantations.

It was only after she fled and found refuge with anti-slavery campaigners in northern England that she was given a voice, by dictating the traumatic story of her life and using it to bring home to Britons the reality of the inhumane industry 3,000 miles away that was enriching their economy.

In her 1831 book, The History of Mary Prince, she lambasted the English for their conduct in the West Indies where “they forget God and all feeling of shame”.

She continued: “They tie up slaves likes hogs – moor them up like cattle, and they [whip] them, so as hogs, or cattle, or horses never were flogged – and yet they come home and say ... that slaves don’t want to get out of slavery. But it is not so.”

With these words and her harrowing descriptions of slavery, including being separated from her mother and sisters as she was examined “in the same manner that a butcher would a calf or a lamb” and sold, Prince became a key part of the campaign which ended with the passing of an abolition law in Britain in 1833.

But while names such as William Wilberforce and Thomas Clarkson have lived on as the heroes of the movement to end British involvement in slavery, the names of its heroines and their role in blazing a trail where men could only but follow has been all but wiped from popular memory.

Historic England, formerly English Heritage, is now seeking to redress the balance by highlighting the role of women in the anti- slavery moment as events are held today to mark the International Day Trade.

Among them were the Quaker Elizabeth Heyrick, whose leaflets and lobbying helped push mainstream abolitionists into a more radical strategy, and Sarah Parker Remond, a black American woman from a freed slave family who toured Britain lecturing on the campaign to end slavery before working as a nurse in London.

The heritage body is asking whether, in a country with no shortage of monuments to Wilberforce, more should be done to commemorate his female fellow travellers, as it launches a series of podcasts explaining their contribution.

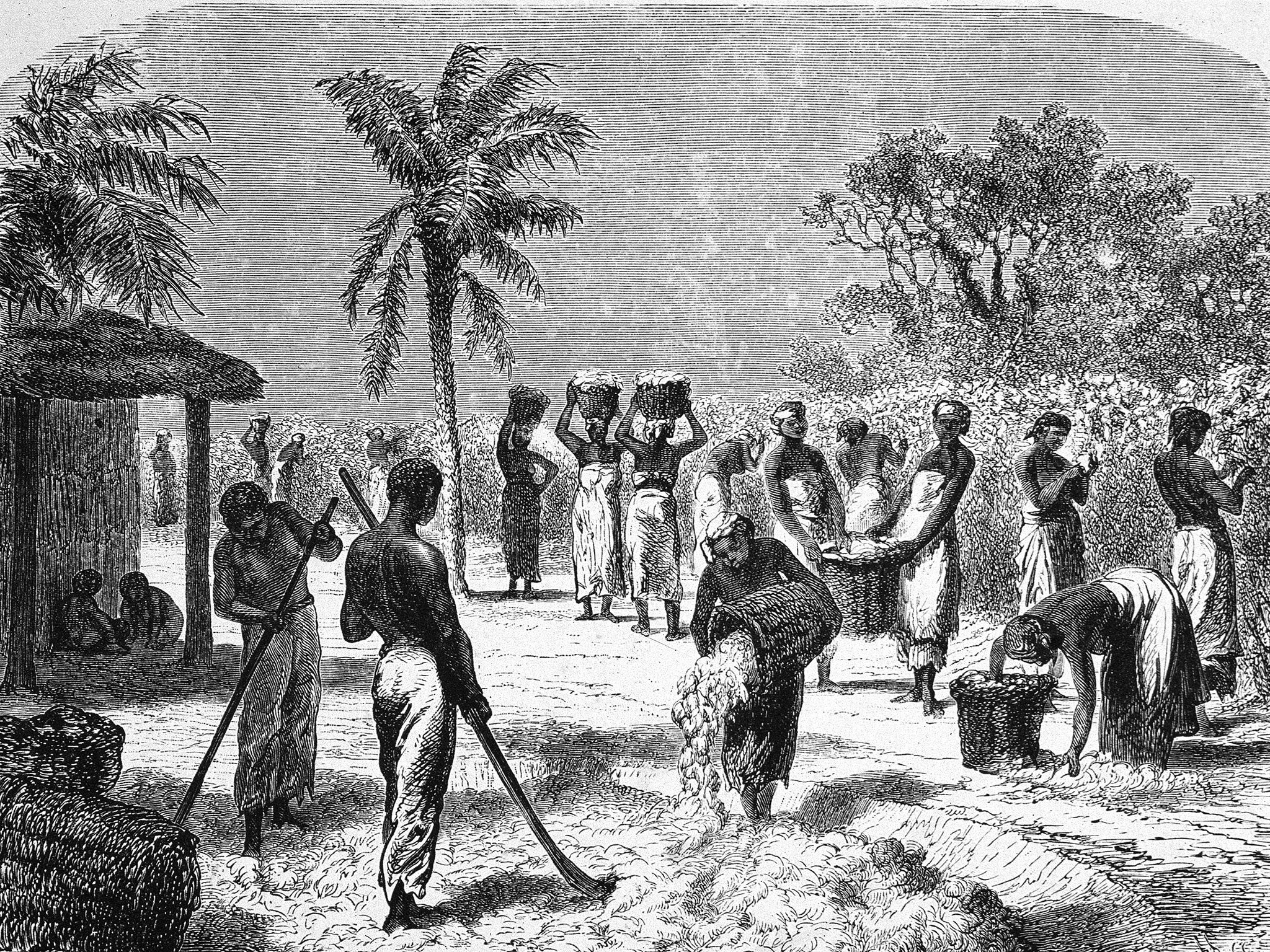

The research highlights how women, at the time deprived of the vote and of any direct political power, took, instead, to writing, and adopted lobbying tactics to mobilise public opinion that were ahead of their time, among them, the organisation of boycotts of slavery-tainted sugar, campaigning visits to shops and households, and mass petitions.

Rosie Sherrington, diversity policy adviser at Historic England, said: “These female campaigners spoke up for enslaved women who often had no voice. They spoke directly to fellow women in this country, who could empathise with their plight. They were instrumental in bringing about an end to slavery, yet their own stories have been lost. We want to celebrate these women and remember their contribution.”

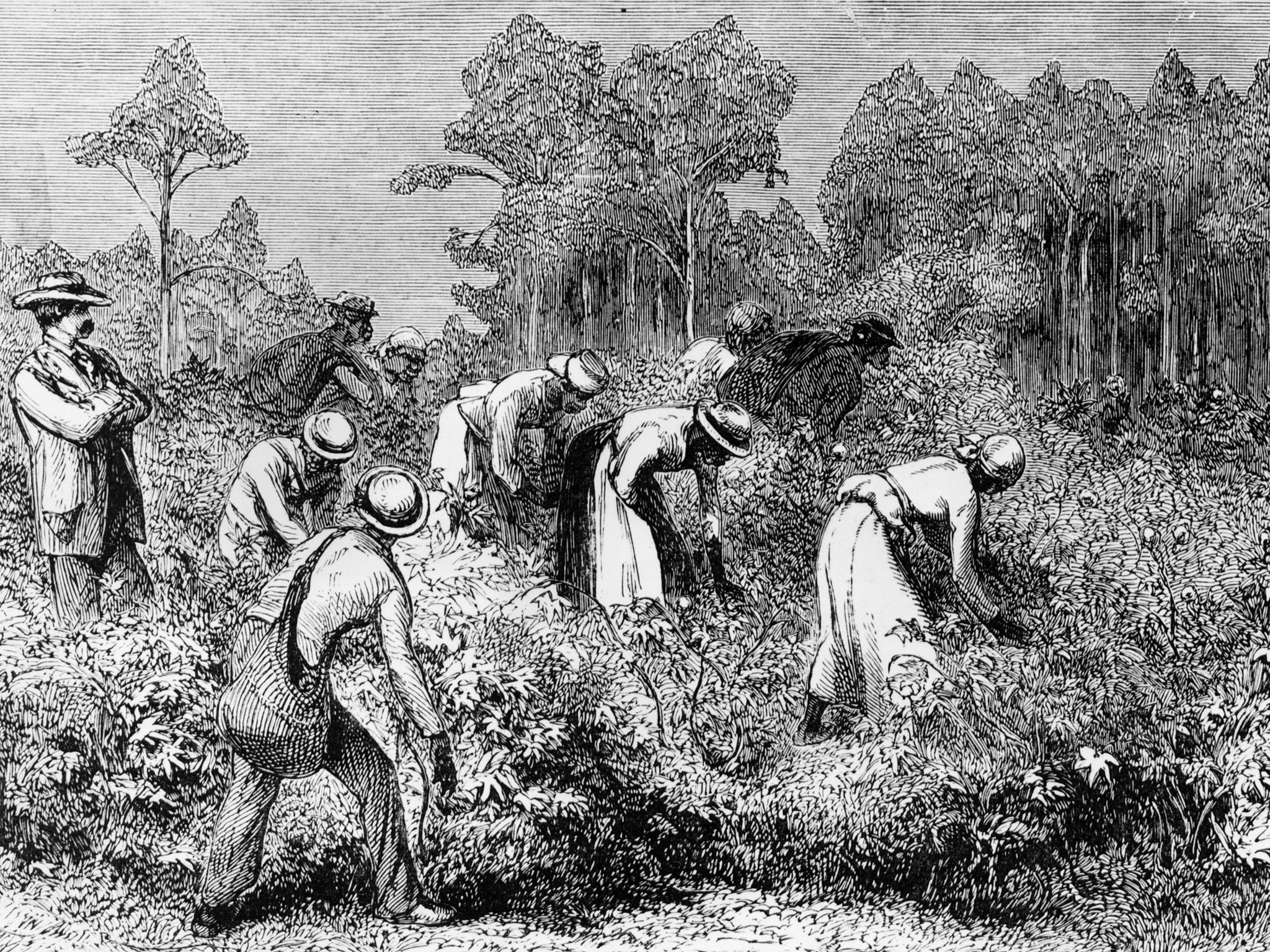

Despite its role in eventually ending slavery, with the Abolition Act in 1833, Britain was one of the most enthusiastic and ruthless exponents of the trade between West Africa and the New World.

Between 1662 and 1807, British and colonial vessels transported 3.4 million slaves across the Atlantic. The trade earned vast sums not only for kingpin merchants and plantation owners, but also for thousands of middle-class Britons, from clergymen to small manufacturers, who often owned several slaves at a time as a commonplace investment.

It was into this society that the likes of Mary Prince, who had been beaten by her master for marrying a freed slave, and Elizabeth Heyrick pitched their efforts to raise consciousness among ordinary Britons of the cruelties being meted out in the colonies.

Prince’s book, which briefly made her a minor celebrity, described in unflinching detail the physical and sexual violence used against her and other slaves as they were traded between masters.

Professor Clare Midgley, of Sheffield Hallam University and one of the first historians to look at the role of women in the abolition movement, said: “Mary Prince wasn’t just telling an individual story – she kept pointing out how this was typical of women’s oppression, sexual abuse, physical violence, overwork. This was a very powerful tool that women took up and circulated to promote the campaign.”

Alongside such personal accounts, women including Heyrick, the widow of a Leicester Methodist, began their work – in her case, directly lobbying grocers in the Midlands city not to stock slave-grown goods.

In 1824, she published an anonymous pamphlet calling for an immediate end to slavery – rather than the gradual approach adopted at the time by Wilberforce and his comrades.

The work, written so forcefully that most assumed it was the work of a man, sold in its thousands as it sought to persuade Britons of their moral duty towards abolition. Heyrick wrote: “The West Indian planter and the people of this country stand in the same moral relation to each other as the thief and receiver of stolen goods.”

The Quaker campaigner was also an astute politician, suggesting that the mushrooming number of female anti-slavery associations should withhold their donations – making 20 per cent of the total – unless the gradualist approach was dropped.

Although it duly was, there was little sign of enthusiasm among the movement’s male leaders for their female counterparts’ assistance. Wilberforce said: “For ladies to meet, to publish, to go from house to house stirring up petitions, these appear to me unsuited to the female character as delineated in scripture.”

Research by University College London shows that women – most of them widows – also featured among Britons who received a share of the £20m that the government paid out in 1834 as compensation to slave owners for the loss of their “property” .

But while the direct involvement of thousands of Britons, including women, in slavery is beginning to be recognised, researchers say the full role of women in its disappearance is yet to be widely understood.

Nicola Raimes, who produced the Historic England podcasts, said: “Women were vital to the abolitionist cause. History has focused on men, but at the grassroots and beyond, women were working to end slavery. Given this was a time when society placed severe constraints on their activities, their contribution is all the more remarkable.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments