The Big Question: Is the Anglican Communion heading towards an inevitable split?

Why are we asking this now?

In recent decades the Anglican Communion has been sharply divided over a number of issues, particularly whether homosexuality should be accepted and tolerated in the Church. But things are really coming to a head. Next month bishops from around the world are due to gather in Canterbury for the once every-10-years Lambeth Conference, but more than 200 from conservative dioceses – predominantly but not exclusively from Africa – have boycotted the event and are this week attending a rival conference in Jerusalem instead.

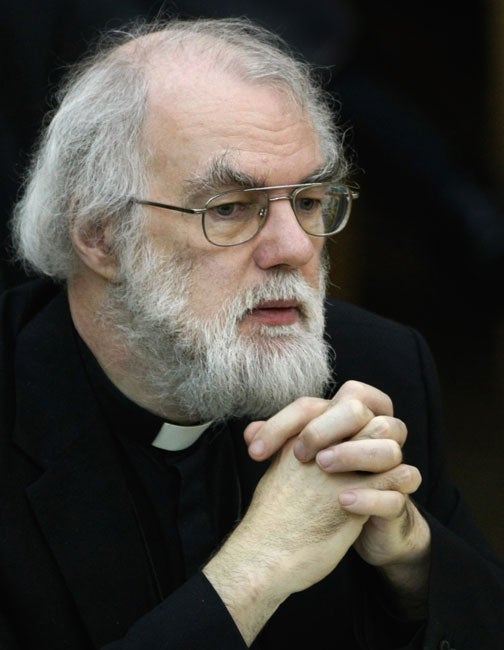

Although organisers of the so-called Global Anglican Future Conference say they have no intention of splitting the Anglican Church or setting up a rival one, it represents one of the most serious threats to the authority of the global leader of the Anglican Church, the Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams.

What are the conservative bishops saying?

That the Anglican Communion has been "broken" by the church in America – known as the Episcopal Church – who caused uproar by consecrating the first professed gay bishop in 2003. They were later joined by Anglicans in Canada, who have also accepted the idea of gay bishops and same-sex unions.

Traditionalists essentially want Anglicanism to return to a much more Bible-based form of Christianity instead of the liberal approach that western bishops and the Church's leadership have generally followed in the past few decades. They believe that developments such as the ordination of women priests and the greater tolerance shown towards homosexuality within the clergy is contrary to their more literal interpretation of the Bible.

The Primate of Nigeria, Archbishop Peter Akinola, is one of the leading organisers of Gafcon. On the opening day of the conference he accused western Church leaders of apostasy and said there would be an "unavoidable realignment" of Anglicanism's power-base towards the conservative dioceses unless Canterbury did more to rein in the liberals. "We want one thing and one thing only," he said. "To restore communion and fellowship. It has failed. We are asking this conference to think about this and come up with something we can do."

How has RowanWilliams reacted?

As far as Gafcon goes, with a deafening silence. Archbishop Akinola has already complained during a recent press conference that his counterpart in Canterbury was "not interested in what matters to us, in what we think or in what we say."

But that doesn't mean the Archbishop has come out fighting for the liberals either. The Archbishop has desperately tried to avoid a repeat of the last Lambeth Conference in 1998 where the Church's attitude towards homosexuality dominated virtually every single discussion and revealed the angry divides within the Communion itself.

Liberals were dismayed earlier this year when it emerged that bishop Gene Robinson, the world's first professed gay bishop, was one of the small number of clergy left off the invitation list for Lambeth. Discussion of homosexuality at this year's Lambeth has also been severely limited to a brief period towards the end of the week-long conference. At next week's General Synod in York, the Archbishop is due to make a speech but whether he will talk about the current divide or not remains unclear.

Why is this such an emotive issue?

Because it goes right to the heart of the debate over the direction of the Anglican Church. For the vast majority of bishops, the last thing they want is one of the largest Christian churches torn apart by bickering over homosexuality, but a split is by no means impossible. Hardliners on both the liberal and conservative side see the current theological crisis in similar terms to the Reformation – a period where implacable theological differences left some with no choice but to break away from the Roman Catholic Church.

How far do attitudes to homosexuality diverge?

In Kenya, Uganda and Nigeria, where homosexuality is illegal and punishable, the ordination of gay clergy would be unthinkable. Some leading western bishops, such as the Archbishop of Sydney, Dr Peter Jensen, are equally opposed. But in the western hemisphere, a greater toleration of gay people has become the norm, with churches essentially turning a blind eye. Technically the Church still believes homosexuality is wrong. A resolution passed at the 1998 Lambeth Conference said homosexuality was "incompatible with Scripture" and that gay people should not be ordained.

But the ordination of Gene Robinson and the attempt by the Church of England in the same year to make Canon Jeffrey John into the Church of England's first gay bishop showed how western Churches were increasingly heading away from that position. The backlash from conservatives over Canon John was so strong that Rowan Williams eventually asked him not to take up the bishopric but the recent civil union blessing of two clergymen in a ceremony that contained all the hallmarks of a full-scale marriage has once more reignited the debate in the UK and across the world.

Could the sides yet reach an agreement?

It doesn't look likely. Entrenched liberals and extreme conservatives are too much at odds. Another problem is that as the conservative bishops are boycotting Lambeth altogether this year it could be another 10 years before the leaders of the Anglican Communion are in the same room together to discuss the issues that are dividing them – by which point it may be too late.

How would a split work in practice?

No-one really knows. The most dramatic scenario would involve a full-scale schism from Canterbury with vast swathes of the African and Southern Churches creating a new centre of leadership that conservative dioceses could then sign up to. The most likely place for that to happen is Africa, where the traditionalists are strongest and Biblical literalism most entrenched.

A lesser version would involve conservatives in liberal countries breaking away from their bishops to join conservative churches. This has already happened in the US where Martyn Minns, a rector in a Virginia church opposed to the ordination of Gene Robinson, was appointed a bishop in the Church of Nigeria.

Would Rowan Williams's position no longer be tenable?

It would depend on how he handles it but presiding over the most dramatic split in the Anglican Communion's history would certainly make his job pretty tricky.

So are the Church's differences really irreconcilable?

Yes...

* The divide between liberals and conservatives is simply too wide for both sides to reach a compromise

* With Gafcon, a split has already technically begun, whether the Anglican Church accepts it or not

* It will be another 10 years before Church leaders can attend another Lambeth, by which point it may be too late

No...

* The Anglican Church by its very nature is made up of conflicting views and theological differences and has weathered many storms

* The vast majority of clergy and lay people don't want to see their Church split in two and will do everything they can to save it

* The fact that conservatives have yet to call for a split shows that ultimately they don't want to break away anyway

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments