The Big Question: Why is our informal economy so big, and how can we make it smaller?

Why are we asking this now?

Baroness Scotland, the Attorney General, has been employing an illegal immigrant to look after her home in west London. Loloahi Tapui, a 27-year-old Tongan woman, has been living in Britain illegally for the past five years after over-staying her student visa.

Lady Scotland denies ever "knowingly" employing an illegal immigrant, and it is possible Miss Tapui was in fact hired by her secretary. But the revelation is still embarrassing, and for two main reasons. First, Lady Scotland is the Government's top law officer. Second, to some extent, she has been caught out by her own law (see below). It comes after a series of reports earlier this year highlighted the scale of Britain's "informal economy," which new estimates suggest is bigger than was previously thought.

Wasn't she involved in creating this law?

Patricia Scotland is the first female Attorney General since the post was created in 1315 and is one of the most senior black figures in Labour. She was a Home Office minister when, in 2006, she helped push the Immigration, Asylum and Nationality Bill through the House of Lords. Under the ensuing Act, employers who knowingly take on illegal immigrants face a two-year prison sentence and an unlimited fine. Those who unknowingly take on illegal workers face a maximum £10,000 fine.

So is the law ineffective?

When the measures came into force, then Home Secretary Jacqui Smith said it would make it easier for employers to carry out identity checks and would deter "slipshod recruitment methods". Miss Tapui has claimed that either Lady Scotland or a member of her office was paying her National Insurance. Yet the Department for Work and Pensions has made it clear that having a National Insurance number does not constitute a right to work. The law also covers a "director, manager, or secretary" working on behalf of an employer, so even if Lady Scotland didn't employ her directly, she could still be in trouble.

Despite widespread public anxieties surrounding the immigration issue, the Home Office has been praised for its attempts to manage a long neglected system. Under Mrs Smith's leadership, and previously under the influence of then Immigration minister Liam Byrne, the department has come down hard on many employers, and launched several high-profile raids on specific workplaces.

Doesn't this sound familiar?

In 1993 two of US President Bill Clinton's nominees for the post of Attorney General resigned after their employment of illegal immigrants as nannies was revealed.

As ever, the latest case raises the spectre of double standards: it's one rule for them, another rule for the rest of us, as goes the popular refrain. Lady Scotland probably wouldn't have employed Miss Tapui if she had known about her immigration status. But the fact that she did employ her is an indication that politicians are not immune to the hazards of employment law that bedevil many others.

Where is this 'informal economy' to be found and how big is it?

A report published in June by the London School of Economics (LSE) estimated that Britain has 618,000 illegal immigrants. Of these, 442,000 are thought to be in London. The capital is where the jobs are, and is geographically closest to most immigrants' point of entry on the south coast. Not all of these illegal immigrants are part of the informal economy – children born to illegal immigrants, for example, who are not migrants themselves but have no right to remain, very rarely work. But most illegal migrants do work, and they congregate in specific sectors: mainly construction, cleaning, catering, and hospitality services. Within those sectors, nationalities bind workers: Ghanaians pick litter; Nigerians clean toilets in the City; Romanians and Poles work in plumbing and maintenance.

Why is it so big?

Critics have long since derided Britain as a "soft touch" on immigration. Since 1997, net immigration to Britain has quadrupled to 237,000 each year, according to MigrationWatch UK. The pressure group estimates that foreign immigrants are now arriving at the rate of around half a million a year, or nearly one a minute.

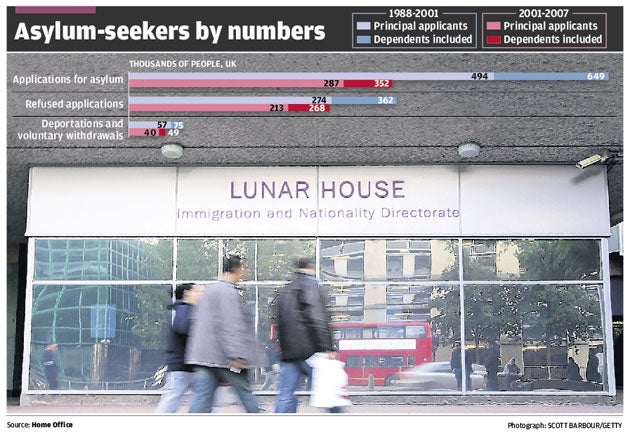

The informal economy is comprised chiefly of those who came here illegally – often in terrifying circumstances – and those who applied for asylum but didn't get it, and haven't been deported yet. It grew particularly sharply between 1997 and 2002, when an economic boom enticed many people to Britain.

There are three specific issues with the economy that distinguish it from regular migration. First, because it is unrecorded, nobody knows its size, it can only be estimated. Second, because they are forced to live underground ("in the shadows") illegal immigrants may be less likely to return home than regular migrants, since they are fearful of getting caught. And third, if illegal immigrants have dependents (usually, but not always, their children) they may not be here legally but can still make legal claims – on human rights grounds, for example – that makes deporting them very difficult.

For all these reasons, the size of the informal economy seems stubbornly large. That is why some politicians are starting to propose radical solutions (see below).

Can it be made smaller?

In practice, reducing the size of the informal economy means preventing those employed in it from working. That in turn means removing them from the country altogether. Yet the present law is woefully slow at deporting people. Between 1998 and the publication of the LSE report, 111,265 illegal entrants had been deported, at the cost to the UK of £11,000 per person. The National Audit Office estimates that the cost of deporting all illegal immigrants would be £4.7bn, while the Institute of Public Policy Research has claimed that at present rates that could take several decades – even if no more immigrants arrived in Britain (which isn't going to happen).

How do we fix this mess?

Some say there are three options: forced mass deportation, the status quo, or an amnesty. The first is inhumane, the second is ineffective. Why not try the third? The LSE report claims that an amnesty could yield £3bn in extra productivity, though it would also cost £1bn in additional public services and social security. There is a compassionate case too for allowing people who wish to work in Britain, and who have taken risks to reach here, to work without fear of prosecution. Having been championed by London Citizens, the capital's largest community organisation, the campaign for such an amnesty has received the support of the London Mayor, Boris Johnson. The Liberal Democrats are in favour, but Labour and the Conservatives oppose it.

Might that backfire?

It could. Opponents argue it would reward criminal behaviour, encourage further immigration to Britain, and risk undermining the wages of British nationals in low-paid sectors. For now, the public seems to agree.

Can anything be done to reduce the size of our underground economy?

Yes...

* With net immigration declining in the recession, current government policy will lower numbers eventually

* High-profile raids on businesses are getting the message across about the Government's tough line

* An amnesty could move many workers into more productive parts of the economy almost at a stroke

No...

* Those who are here illegally are even less likely to return home than those here legally

* Britain continues to be easier to reach than many other countries, and the new arrivals won't stop

* An amnesty is politically unlikely despite the growing number of people who support the campaign

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments