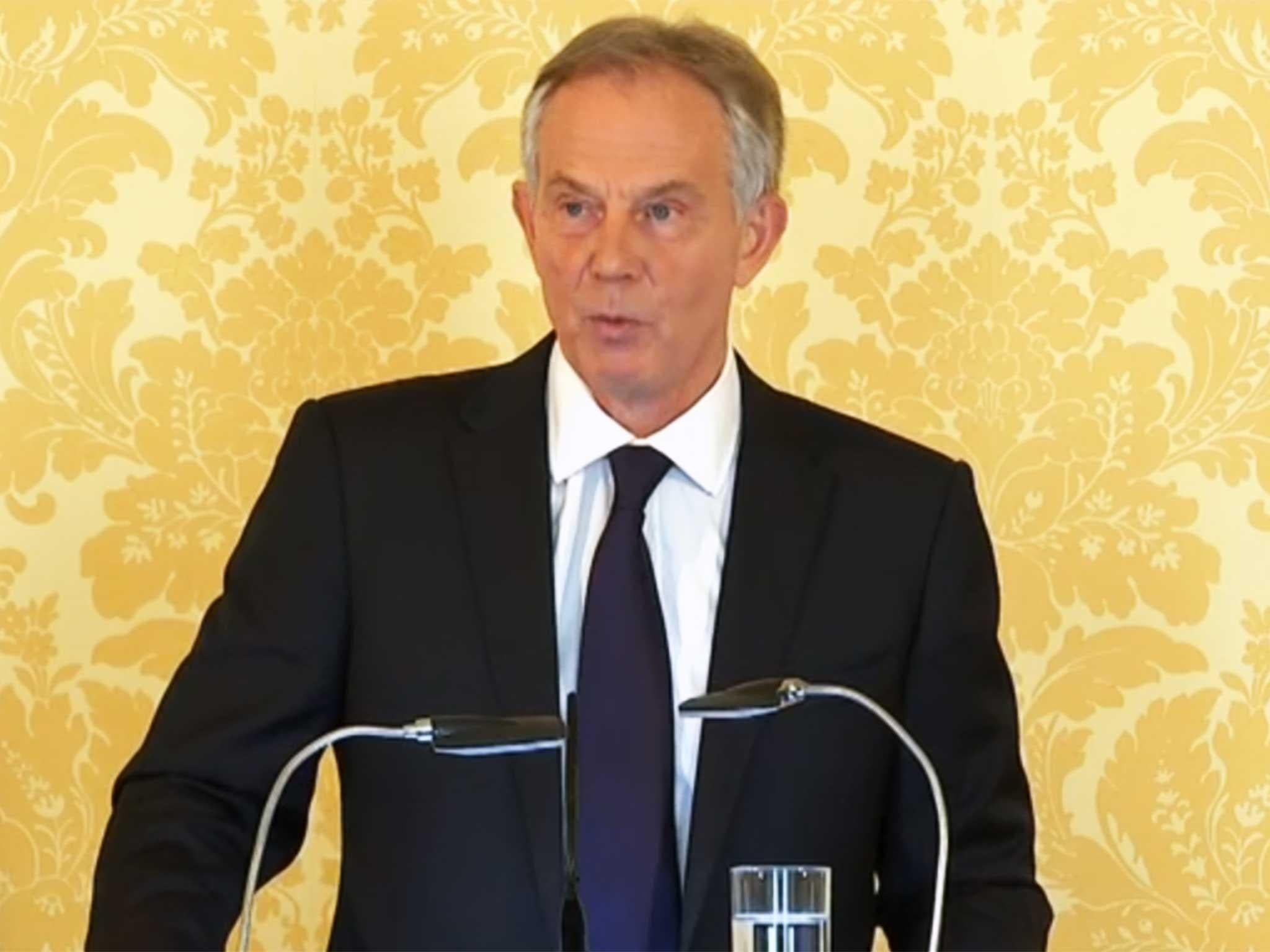

Chilcot report: Tony Blair's response to the Iraq War inquiry in full

'I believe that it was better to remove Saddam Hussein and why I do not believe this is the cause of the terrorism we see today whether in the Middle East or elsewhere in the world'

Here is Tony Blair's statement responding to the Chilcot report in full:

“The report should lay to rest allegations of bad faith, lies or deceit. Whether people agree or disagree with my decision to take military action against Saddam Hussein; I took it in good faith and in what I believed to be the best interests of the country.

”I note that the report finds clearly:

:: That there was no falsification or improper use of Intelligence (para 876 vol 4)

:: No deception of Cabinet (para 953 vol 5)

:: No secret commitment to war whether at Crawford Texas in April 2002 or elsewhere (para 572 onwards vol 1)

Follow the latest live updates on the Chilcot report

The inquiry does not make a finding on the legal basis for military action but finds that the Attorney General had concluded there was such a lawful basis by 13th March 2003 (para 933 vol 5)

However the report does make real and material criticisms of preparation, planning, process and of the relationship with the United States.

These are serious criticisms and they require serious answers.

I will respond in detail to them later this afternoon.

I will take full responsibility for any mistakes without exception or excuse.

I will at the same time say why, nonetheless, I believe that it was better to remove Saddam Hussein and why I do not believe this is the cause of the terrorism we see today whether in the Middle East or elsewhere in the world.

Above all I will pay tribute to our Armed Forces. I will express my profound regret at the loss of life and the grief it has caused the families, and I will set out the lessons I believe future leaders can learn from my experience.“

The intelligence assessments made at the time of going to war turned out to be wrong, the aftermath turned out to be more hostile, protracted and bloody than ever we imagined.

The coalition planned for one set of ground facts, and encountered another. And a nation whose people we wanted to set free and secure from the evil Saddam became instead victim to sectarian terrorism.

For all of this I express more sorrow, regret and apology than you may ever know, or can believe.

Only two things I cannot say. It's claimed by some that by removing Saddam we caused the terrorism today in the Middle East, and that it would have been better to have left him in power. I profoundly disagree. Saddam was himself a wellspring of terror, a continuing threat to peace and to his own people.

If he'd been left in power in 2003 then I believe he would once again have threatened world peace and when the Arab revolutions of 2011 began he would have clung to power with the same deadly consequences that we see in the carnage in Syria today.

Whereas at least in Iraq, for all its challenges, we have today a government that is elected, is recognised, is internationally legitimate, and is fighting terrorism with the support of the international community.

The world was, and is, in my judgement, a better place without Saddam Hussein.

Secondly, I will never agree that those who died or were injured made their sacrifice in vain. They fought in the defining global security struggle of the 21st Century against the terrorism and violence which the world over destroys lives and devastates communities and their sacrifice should always be remembered with thanksgiving and with honour when that struggle is eventually won as it will be.

I know some of the families cannot and do not accept this is so. I know there are those who can never forget or forgive me for the having taken this decision and who think that I took it dishonestly.

As the report makes clear there were no lies, Parliament and Cabinet were not misled. There was no secret commitment to war, intelligence was not falsified and the decision was made in good faith.

However, I accept that the report makes serious criticisms of the way decisions were taken and again I accept full responsibility for these points of criticism even where I do not fully agree with them.

I do not think it is fair or accurate to criticise the armed forces, the intelligence services or the civil service.

It was my decision they were acting upon.

The armed forces in particular did an extraordinary job throughout our engagement in Iraq, in the incredibly difficult mission we gave them. I pay tribute to them, any faults derived from my decisions should not attach to them.

They are people of enormous dedication and courage and the country should be very proud of them.

Today is therefore the right moment to go back however, and look at the history of that time so that those, even if they passionately disagree, will at least understand why I did what I did, and learn lessons so that we do better in the future.

First: Why was Saddam a threat? My Premiership changed completely on September 11 2001. 9/11 was the worst terrorist atrocity in history.

Over 3,000 people died that day in America, including many British people, making it the worst ever loss of life of our own country's citizens from any single terror attack.

In fact, 9/11 was not of course the first terror attack. Prior to then, 23 countries had suffered terrorist attacks of this nature: in 2002, 20 different nations lost people to terrorism.

For over 20 years as well, the regime of Saddam had become a notorious source of conflict and bloodshed in the Middle East.

He had attempted a nuclear weapons programme, only halted by a preventive strike by the Israeli military in 1981, and used chemical weapons in the war he began with Iran, a war which lasted seven years with around a million casualties.

Out of the Iranian experience came Iran's own nuclear weapons programme.

He invaded Kuwait in 1990, he used chemical weapons extensively against his own people, for example in the massacre of Halabja where thousands died in a single day.

The international community made frequent attempts to bring him into compliance with UN resolutions, calling for him to give up his programmes.

As at March 2003 he was in breach of no fewer than 17 such UN resolutions.

In 1998, following the ejection of UN weapons inspectors from Iraq, President Clinton and I authorised military strikes on his facilities and from that point regime change in Iraq became the official policy of the US administration.

In a country where a majority of Iraqis, Shia Muslims and 20 per cent of the population of Kurds, he ruled with an unparalleled brutality with a government drawn almost exclusively from the Sunni 20% minority, though many of his victims were also Sunni.

Saddam was not the only developer of weapons of mass destruction.

Libya had a programme, North Korea was trying to obtain nuclear technology.

The network of the Pakistani scientist AQ Khan was an active proliferator of such techonology and Iran's program had begun.

But only one regime had actually used such weapons. That of Saddam.

Intelligence still valid indicated al Qaida wanting to acquire such material and 9/11 showed they were prepared to cause mass casualties.

So it's important now that we're here, 15 years after 9/11, to recall the atmosphere at that time.

America had never suffered such an attack on its own soil before. Its population were devastated. They regarded themselves at war.

The Taliban who had given sanctuary to al Qaida had been removed from power in Afghanistan in November 2001.

But the 2002 Bali bombings, in which over 200 victims, mainly Australians, lost their lives, showed the continuing threat. All western nations were changing their security posture, we were in a new world.

And at that time we did not know where the next attack, threat or danger would come from. The fear of the US Administration which I shared was the possibility of terrorist groups acquiring, either by accident or design, chemical weapons, biological weapons, or even a primitive nuclear device.

The report accepts that after 9/11 the calculus of risk had changed fundamentally. We believed we had to change policy on nations developing such weapons in order to eliminate the possibility of WMD and terrorism coming together.

Saddam's regime was the place to start.

Not because he represented the only threat, but because his was the only regime actually to have used such weapons, there were outstanding UN resolutions in respect of him, and his record of bloodshed suggested he was capable of aggressive, unpredictable, catastrophic actions.

In addition, the UN sanctions imposed on Iraq were crumbling and therefore containment was faltering.

The final Iraq survey report which was conducted into Saddam's WMD programme and ambitions after the Iraq war, and whose findings are accepted in this report, found that Saddam did indeed intend to go back to developing the programmes after the removal of sanctions.

So I ask people to put themselves in my shoes as Prime Minister.

Back then, barely more than a year from 9/11, in late 2002 and early 2003, you're seeing the intelligence mount up on WMD.

You're doing so in a changed context of mass casualties cause by a new and virulent form of terrorism.

You have at least to consider the possibility of a 9/11 here in Britain and your primary responsibility as Prime Minister is to protect your country.

These were my considerations at the time.

The lead up to war - there was no rush to war.

The inquiry rightly dismisses the conspiracy theory that I pledged Britain unequivocally to military action at Crawford, Texas, in April 2002.

I did not and could not, as they explicitly in their report conclude.

I was absolutely clear publicly and privately however that we would be with the USA in dealing with this issue, and I made that clear in the note to President Bush of the 28th of July 2002. But I also said we had to proceed in the right way and I set out the conditions necessary, especially, that we should then go down the UN route and avoid precipitate action as indeed the inquiry report finds.

So, as again the inquiry finds, I persuaded a reluctant American administration to take the issue back to the UN. This resulted in the November 2002 UN Resolution 1441 giving Saddam 'a final opportunity' to come into 'full and immediate compliance with UN Resolutions' and to cooperate fully with UN inspectors.

Any non-compliance was defined as a material breach.

Finally, and only under threat of military action, Saddam permitted inspectors to return but his co-operation was neither full nor immediate - see the report of the inspectors to the UN in January 2003 and that of the 7th March 2003, again referred to in the body of the report.

However, by then there was substantial disagreement at the UN Security Council. America wanted action, President Putin and the leadership of France did not.

In a final attempt to bridge the division I agreed with the inspectors a set of six tests based on Saddam's non-compliance with which he had to comply immediately, which included things like interviews with those responsible for his programme and which up to then had been refused except in a country where obviously these people would be subject to intimidation.

So these six tests were drawn up in a resolution accompanied by an ultimatum that non-compliance would result in military action.

So again I secured American agreement to a new resolution, vetting tests which if he had passed would have avoided military action.

But the United States understandably insisted that in the event of continued failure, the UN had to be clear that action would follow. And this was the approach rejected by Saddam.

The Americans and the UK and other partners from over 40 nations had assembled a force in the Gulf ready for military action.

President Bush made it clear he was going to act.

The British Government, under my leadership, chose to be part of that action, a decision endorsed by Parliament, with the leaders of the opposition being given access to exactly the same intelligence and advice as given to me.

Now, the enquiry finds that as at the 18th of March, war was not, and I quote, the “last resort”.

But given the impasse of the UN and the insistence of the United States for reasons I completely understood, and with hundreds of thousands of troops in theatre which could not be kept there indefinitely, it was the last moment of decision for us, as the report indeed accepts.

However, as at the 18th of March, there was gridlock at the UN.

In resolution 1441 it had been agreed to give Saddam one final opportunity to comply.

It was accepted he had not done so. In that case, according to 1441, action should have followed.

It didn't because by then, politically, there was an impasse.

I say the undermining of the UN was in fact refusal to follow through on 1441, and with the subsequent statement from President Putin and the President of France, that they would veto any new resolution authorising action in the event of non-compliance, it was clearly not possible to get a majority at the UN to agree a new resolution.

As the then president of Chile explained there was no point since any decision by a majority would be vetoed.

So, on the 18th of March, and this is the vital thing to understand, given especially what Sir John said this morning, we had come to the point of binary decision: right to remove Saddam or not, with America or not.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks