The Big Question: What was the Magna Carta, and are its contents relevant to us today?

Why are we asking now?

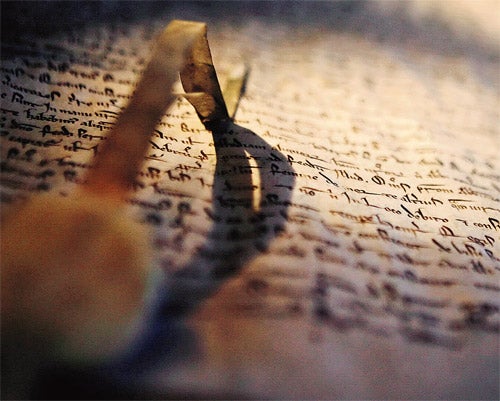

In a New York auction house last night, a handwritten document more than 700 years old went under the hammer. It is a copy of the Magna Carta, dating from early in the reign of Edward I. It once belonged to the Earl of Cardigan, the imbecilic cavalry officer who led the charge of the Light Brigade, and gave his name to what was then a fashionable garment. His family retained their copy of Magna Carta for about 500 years, then sold it in 1984 to the Texan billionaire, Ross Perot, for $1.5m (750,000). He loaned it to the National Archives in Washington, so that it could lie alongside the Declaration of Independence and the US constitution. This year, the Ross Perot Foundation decided to sell the manuscript. It is the first time a copy of Magna Carta has been auctioned, and could be the last.

The sale will inevitably focus minds on the question of whether British schoolchildren should be taught about the Magna Carta, in the way that Americans have to learn about the Declaration of Independence. Magna Carta is taken so seriously in the US that the American Bar Association occasionally gathers at Runnymede, Surrey, where it was originally signed, to pledge allegiance to its principles.

How many copies are there?

No one knows how many copies of the original document were distributed in 1215. There must have been quite a few. The royal chancellery reportedly sent one to every sheriff and bishop in England. Only four have survived. Two are held by the British Library, one is in the archives of Salisbury Cathedral, the other in Lincoln Cathedral. There are another 13 copies made during the course of that century, 11 of which are in the UK. There is one copy in the National Library of Australia. The other, which until yesterday belonged to Mr Perot, dates from 1297, the year when Magna Carta became law. Oxford's Bodleian Library has one of the oldest copies, dated 1217, which it put on display for one day only last week. When the doors opened, there was a queue of 150 people outside.

What was special about it?

Until 1215, the King of England was an absolute monarch. In theory at least, the will of the King was the law of the land. In practice, there were always powerful nobles who would challenge his power, if they thought they could get away with it. There were no rules in the contest between King and barons, except one whoever had the strongest army got what he wanted. Then on 15 June, 1215, King John met a delegation of barons on Runnymede island, and between them they drew up a document, written in Latin, which they called the Big Charter, setting out the limits and terms of the King's powers. It is seen as the symbolic beginning of the rule of law in England. For the first time, the English had something in writing to protect them against arbitrary rule.

Is the whole document relevant?

No. There are clauses which have long since become pointless, and others which are slightly shocking if judged by contemporary standards. For instance, there is the blatant discrimination in Clause 54: "No one shall be arrested or imprisoned on the appeal of a woman for the death of any person except her husband." Clause 50, which bars the King's ally, Gerard de Athee, Sheriff of Gloucester, and all his relatives from holding public office, was defunct within a year. Much of the document is concerned with the privileges of the aristocracy rather than the rights of anyone else. If Clause 21 still applied, neither Jeffrey Archer nor Conrad Black would have gone on trial in ordinary courts, because it specified that lords could be judged only by other lords.

There are a lot of quite technical matters about the management of land and rivers. Clause 11 would be anathema to modern banks and finance companies because it says that if a man dies owing money, his widow is not responsible for his debts. Though that sounds nice, the clause has anti-semitic overtones, because it was assumed that most moneylenders were Jews.

What are its most important clauses?

Clause 39 is possibly the best known. It has never been rescinded and is immediately relevant to the present government. It says that "No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights and possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any other way, nor will we proceed with force against him, or send others to do so, except by the lawful judgement of his equals or by the law of the land." When MPs try to block the Government's proposal to hold suspected terrorists for up to 42 days without charges, they will be, in effect, upholding a piece of law signed by King John 792 years ago.

Clause 38 is almost as important. It said: "No official shall place a man on trial upon his own unsupported statement, without producing credible witnesses to the truth of it." Most of the worst injustices in recent legal history have occurred when people have been convicted on no real evidence other than confessions made under interrogation. Clause 40 promised to end the system by which rich offenders could simply buy their way out of trouble. For a medieval monarch to make promises like these, even with his fingers figuratively crossed, was an extraordinary moment in history.

Was John a good King?

In the opinion of his contemporaries, John was a thoroughly bad king. "Hell is too good for a horrible person like him," the 13th-century historian Matthew Parish reckoned. He was unpredictable, devious and worst of all, unlucky. In contrast to his brother, Richard the Lionheart, he had the reputation of being a shocking coward. His nickname was "Soft sword". He was embroiled in one of England's incessant wars with France, which was very expensive, and his officials used unscrupulous methods to raise money. This explains some of the odd clauses in Magna Carta. One said that no widow should be forced to remarry if she did not want to. This was to stop the king putting rich widows up for sale.

There were only two good things about King John; one was that he was such a disaster that the barons forgot their mutual rivalries and combined against him. He had also made an enemy of the Pope by appointing one of his favourites Archbishop of Canterbury. But as soon as he had sorted out his differences with the Pope, John disowned Magna Carta, and resumed the war with the barons, during which the entire contents of his treasury was dropped in the Wash, in Lincolnshire, and lost. A few days later, he did England another service he died. His son and heir, Henry III, was only eight years old, and his Protector reinstated Magna Carta to placate the barons. It was made law by Henry's son.

Was the signing of the Magna Carta one of history's greatest moments?

Yes...

* For the first time, it stated that an Englishman who had not broken the law could not have his liberty or property taken away by the state

* It set down in writing that even the King was not above the law

* All subsequent steps towards democracy, including the rise of Parliament, followed from the Magna Carta

No...

* The parties who signed were not interested in civil rights. They were doing a deal to avoid civil war

* Its purpose was to protect the nobility from the King. It did nothing for the peasant

* It discriminated against women and Jews, and offered nothing for the Scots or the Irish, or any foreigners living in England

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies