Ebola outbreak: Sierra Leone is battling to contain the virus, but one area of the country remains untouched

Koinadugu's success has been the result of concerted, early efforts to staunch the spread of the disease, and most of the planning has fallen to one man

Only in Koinadugu does he relax. That's where his fears of Ebola fade.

John Caulker, an executive director of the non-profit Fambul Tok, travels across Sierra Leone these days tense with worry about contracting the dreaded disease. He worries in the bustling capital of Freetown and in the smallest villages. But not in Koinadugu.

"It's a sense of relief," Caulker says, "a sense that here you are going to be OK."

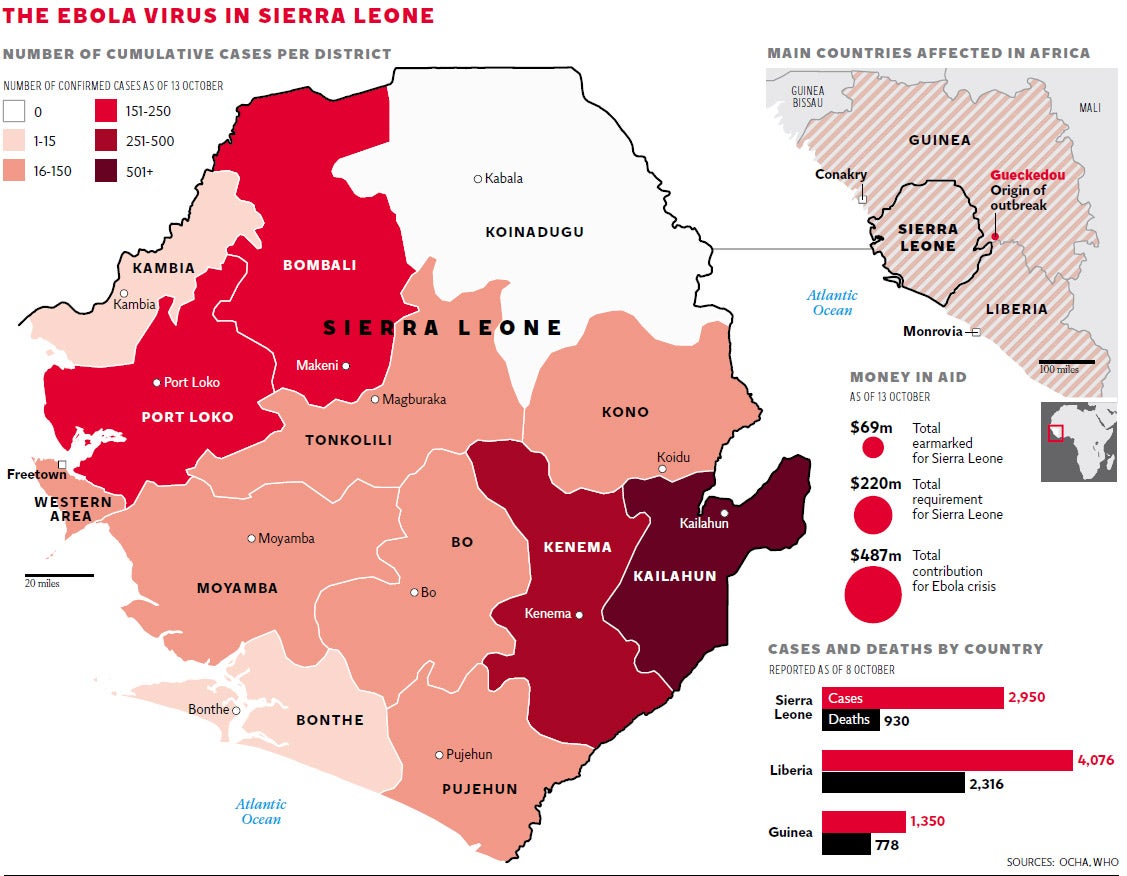

The last region in Sierra Leone untouched by Ebola* sits in the rugged, mountainous north, in a place called the Koinadugu District. It is a poor place, dependent on small farms and gold mines, the largest of the country's 14 districts by land size and home to 265,000 residents. It borders Guinea, where the current Ebola outbreak began and first spilt over into Sierra Leone. Koinadugu is surrounded by districts dealing with hundreds of Ebola cases.

But Koinadugu has kept the virus at bay.

Konte, 43, grew up in the town of Kabala, the capital of Koinadugu, but left years ago to pursue his education in the United States, studying at Howard University and the University of Toledo. He runs an economic consulting business with offices in West Africa called Transtech International. He helped to privatise Sierra Leone's telecommunications industry. Konte has done well for himself. He maintains strong political ties to the country's ruling party. He lives in Washington.

But in May, as the Ebola outbreak smouldered, he began thinking about ways that he could help his home district. He was convinced that the government and international aid groups were not doing enough.

Konte wasn't an Ebola expert, hadn't read up on the latest infection control standards and didn't understand in great detail how the virus was transmitted. He knew only that Ebola was spread by close contact with body fluids. So he focused on limiting exposure. And, to him, that meant limiting movement. "The whole idea is it's not killing rich people, it's not killing middle-class people – it's killing poor people who move from one place to another looking for work or something to eat," Konte says.

In June, he flew to Sierra Leone, plans in hand. He arrived in Koinadugu with big drums of chlorine for disinfection and thousands of pairs of rubber gloves and face masks. He donated 10 million Leones (about £1,430) to the district's anti-Ebola efforts and promised to renew the donation every month for a year. Not much. But it was enough. The local press hailed him as a philanthropist.

Konte's first step was convincing district politicians, along with the important traditional tribal leaders, that they could not wait for help. And he needed their support. "I cannot just start passing laws. I don't have the authority to do that," he says. "The only thing I enjoy there is the respect that they give me."

He was persuasive and, especially important, willing to spend money. He organised a district Ebola task force, gave each of the 10 members a stipend and appointed a former Médecins Sans Frontières official named Fasineh Samura as the head. Together, they set out to implement Konte's plans.

The strictest measure was to draw a ring around the district and restrict who went in or out. The mountains helped. But so did checkpoints, where guards stood armed with thermal thermometers and chlorinated water – and a pass system that prevented most residents from leaving. Visitors needed a local resident to vouch for them. Aid groups such as Médecins Sans Frontières have criticised such quarantines, which exist in several regions of Sierra Leone, arguing that they only worsen suffering.

But Konte, relying on his business background, devised some potential solutions. While most small business owners were not allowed to leave Koinadugu to visit Freetown on supply runs, he set up a £28,000 revolving fund to make loans for the importation of food, fuel and medicine, with deliveries co-ordinated by the task force.

The district's vegetable growers, the country's primary produce supplier, were forced to share a small, communal fleet of lorries to ship their goods. And instead of these trucks being stuffed with five people, each carried one driver and one or two people called "manifesters" who tracked the shipments and payments.

These mango, rice and bean farmers were upset with the new rules. Konte recalls that they took to the airwaves to criticise his plans, to wonder who gave him the authority to act like he was the president of Sierra Leone. "I understood their position," he says. "To cut off a business from making profits is very difficult."

He tried explaining why the changes were necessary. It also helped that he gave them each 2,000 Leones – the equivalent of 30p – to cover higher costs. "I was able to overcome that and get their support," he says.

Responsibility for stopping Ebola was shared. Chiefdoms were asked to form neighbourhood watch teams to enforce the new rules and educate people about the disease. Community leaders, such as the women working in markets and drivers of the popular motorcycle taxis, were encouraged to explain Ebola and why the new restriction were required.

Fambul Tok, a non-profit agency aimed at civil war reconciliation efforts, shifted its focus to Ebola education. Each bit helped, broadening the duty of keeping Ebola away. "It's a collective determination to make sure that they remain Ebola-free," Caulker, of Fambul Tok, said. "The people in Koinadugu are trying to defend their status."

Konte's plan also targeted faith healers. The task force dispatched teams to talk to these traditional medicine practitioners, give them money and beg them not to treat anyone appearing to suffer from Ebola. The disease's first cases came to Sierra Leone from people infected during a faith healer's burial in Guinea.

Faith healers offer hands-on treatments that can involve bloodletting, all of which carry risks of transmitting Ebola. "When it comes to traditional African healers, we had to pay extra attention," Konte says. People trust them. They are popular. A faith healer with Ebola could be disastrous. "It would've wiped out our community."

The district has faced close calls. Last month, a man sick with Ebola was smuggled into Kabala from the neighbouring Port Loko district, where the disease is rampant. His wife was a native of Koinadugu, and the couple stayed out of sight at her father's house. But health officials were alerted and the couple were escorted out of Koinadugu. People who had close contact with the infected man were quarantined. No new cases of Ebola were found.

Click HERE for full-size version of graphic

Konte says he knows that the anti-Ebola measures have been hard. But he doesn't see any other way. "You cannot have comfort and take care of this Ebola thing," he says.

Koinadugu's status as Ebola-free remains fragile, prone to break with the slightest mistake. The town of Makeni, just an hour away, has seen an explosion in the number of new infections. Konte compares it to seeing your neighbour's house on fire and wondering just how long before the fire reaches your house, too. As a result, the district's Ebola task force this week cut the number of passes allowing people to leave Koinadugu.

Residents need to remain vigilant, he says. The stakes are higher in Koinadugu, Konte knows, growing with each passing day as the outbreak rages just outside its doors.

This article first appeared in 'The Washington Post'

*UPDATE: On 16 October 2014, a day after this article was published, Koinadugu registered its first two cases of Ebola.

The ethics of quarantine

By Daniel Sokol

The price of keeping Ebola at bay is some degree of personal freedom, some loss of autonomy. In quarantine scenarios, individual interests give way to the collective good.

A central aspect of quarantines is the legitimacy of the restrictive measures, because you're always going to restrain people's ordinary rights (such as freedom of movement). Are the restrictive measures proportionate? Are they effective? Do they unfairly affect one particular part of the population?

Here, the financial loss, arising from limitations in trade and other prohibitions, has been mitigated by the donations of a benefactor. The local population appears to have been educated about the illness by influential community leaders, and understands the rationale for the quarantine. Quarantine may be in their cultural memory, as it has been practised in Africa and elsewhere for centuries as an effective way to limit the spread of infectious disease.

The fact that the quarantine has been self-imposed rather than dictated by "foreigners" has probably played a part in its success, and it must be remembered that, in many African communities, there is a greater sense of collective responsibility and community spirit than in Western countries, where autonomy is more individual and atomistic.

The co-operation of traditional healers is also key, as we know that in past Ebola outbreaks they have played a part in spreading the disease through invasive "healing" procedures.

The difficulty arises if the fragile balance is broken, and if the discipline required to keep to the rules is lost. In such situations, quarantine may lead to secrecy, loss of trust, and, ultimately, more harm than good.

Successful quarantine rests on trust that each person will respect the rules. That trust can be abused, for example by a person or family hiding an illness or secretly allowing an infected visitor into the community.

Those under quarantine must be mentally tough, and the psychological impact of quarantine can be severe. Ideally, supportive measures should be in place to address that impact.

In this case, it appears that the restriction on personal liberty is justified by Ebola's potential to cause extreme physical and economic harm to individuals and the community at large.

Daniel Sokol PhD is a medical ethicist and barrister

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments