Rich African states 'squander their wealth' as children die

Some of Africa's biggest "success stories" are accused today of squandering money they could be using to help prevent millions of children dying.

A report says that many of the developing countries hailed by the West as economic miracles are using little of their new wealth to tackle easily preventable diseases that kill millions of the most vulnerable, in particular newborn babies, young children and women in childbirth.

The findings from Save the Children are, the aid agency says, an indictment of governments in sub-Saharan Africa. Nearly half of the worst performing countries are in Africa, despite some boasting economic growth rates three times the global average.

The agency has plotted rates of child mortality against UN data on per-capita income to publish an index showing which countries are making the best use of their new prosperity. Oil-rich Angola emerges worst. Although it now has a per-capita income high enough to put it in the "middle income" category of states, more than one in four children dies before their fifth birthday. Sierra Leone is the second-worst performing, with 118 more children per 1,000 dying than should do for the amount of cash coming into the country. South Africa and Nigeria are also criticised.

However, Bangladesh, despite its poverty, is one of the few countries to improve significantly child health. Its wealth per head grew at a rate of 23 per cent between 2000 and 2006, and the increased prosperity has at least partly been converted into a better deal for the poor. During the same period, its child mortality rate has fallen by 25 per cent. India's per-capita income grew 82 per cent in the same period, but it managed to cut child mortality rates by only 19 per cent.

Some 10 million children die each year of illnesses related to poverty and limited access to medical treatment, and 41 countries account for 9 million of those child deaths. The 10 countries with the worst record for converting new wealth into child survival are Angola, Sierra Leone, Niger, Chad, Mali, Burkina Faso, Guinea, Nigeria, South Africa and Cameroon.

The developing-country governments praised for having lower child-mortality rates than their income suggests include Nepal, Yemen, Malawi, Indonesia, Tanzania, Bangladesh, Egypt, Madagascar, The Philippines and China. Save the Children says governments must prioritise free health care, clean water and sanitation and to support women's education.

"All countries can cut child mortality if they pursue the right policies and prioritise their poorest families. Good government choices save children's lives but bad ones are a death sentence," said David Mepham, policy director of Save the Children.

The lottery of child survival in Sierra Leone

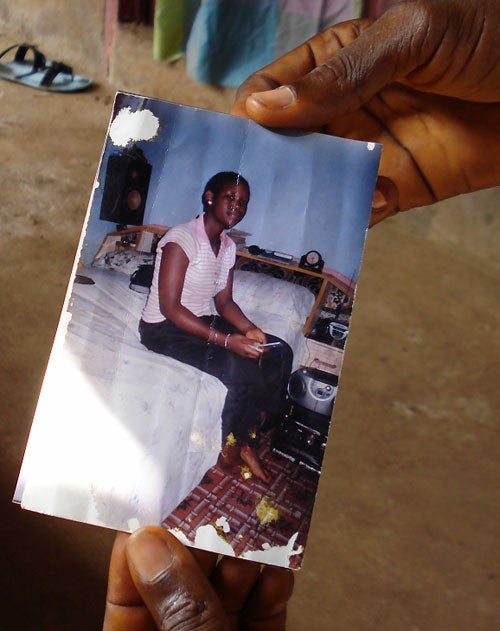

Ramatou Bangura, newborn girl

Ramatou Bangura might be a bouncing four-month-old now had she had been born in Britain, or even Bangladesh, rather than Sierra Leone. Ramatou's mother Abie was just 19, fit and healthy, when she gave birth. Now Abie's husband, Hassan, clutches his wife's death certificate and his daughter's burial report. In the space for cause of death, a Freetown doctor has written "sepsis and obstructed labour".

The entry does not tell the full story of the painful ordeal Abie and her baby endured in a chronically under-funded health system. Abie needed a Caesarean. But the hospital near her home in Kroo Bay, a slum in the capital, charged £60 for that. Abie's husband, a painter and sign writer, borrowed the money, but the delay led to complications.

His wife needed an urgent blood transfusion but that would have incurred an additional charge, so Hassan had to rush around Kroo Bay in a desperate search for blood donor. But it was too late: mother and daughter died within 24 hours of each other.

This tragedy happened despite Sierra Leone's civil war ending five years ago. Aid has poured in and the economy is beginning to recover. It is rich in diamonds and natural resources and at last has a democratic government. Its roads are being paved, and some parts of the capital are thriving. But health care, supposed to be free for mothers and babies under five, is abysmal.

The national health budget is £7m a year, the equivalent of £1.80 per person, per year. Clinics, sometimes lacking electricity, say they have no choice but to charge. It still has the worst under-five mortality rate and one of the worst maternal mortality rates in the world. Even routine infections such as diarrhoea can be lethal. Few can afford steep healthcare charges. Most live on £1 a day but it costs £2.50 to treat a child for malaria.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments