The Big Question: As its leaders gather in Uganda, what purpose does the Commonwealth serve?

Why are we asking this now?

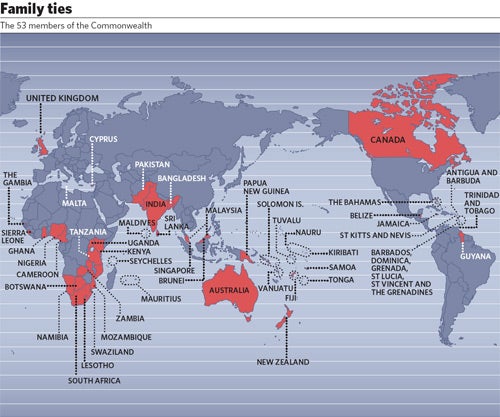

Because the leaders of the 53 Commonwealth nations are meeting in the Ugandan capital, Kampala, from today when the Queen opens their biennial summit, known affectionately as the CHOGM (pronounced Choggum). The question about the association's relevance comes to the fore every time a Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting takes place, as people wonder why so many leaders of former British colonies remain so interested in using up airmiles to hob-nob with the Queen. The secretary-general of the Commonwealth, Don McKinnon, was busy batting away the "irrelevance" accusations in his online blog from Kampala yesterday.

In fact, the Commonwealth is much more than a talking shop. It is a formidable network whose rich members – such as the UK, Canada and Australia – get involved in sharing business best practices and technology with the Commonwealth members from developing nations. The Commonwealth states, representing 2 billion people, make up a giant melting pot of different races and faiths, united by shared democratic values. And, of course, by a love of cricket. The club also provides an opportunity, particularly at summit level, for the burning political and trade issues of the day to be aired informally at the leaders' traditional "retreat".

What's on the agenda?

The summit has been overshadowed by President Pervez Musharraf's declaration of a state of emergency. That delivered a slap in the face to the Commonwealth, which sets great store on its core values, and posed the organisation with the challenge of deciding whether to suspend Pakistan for the second time. A committee of Commonwealth foreign ministers was grappling with the decision yesterday.

On the surface, it looked like an open and shut case after General Musharraf was given until yesterday to comply with a series of demands on restoring democracy, including the lifting of the emergency and shedding his military uniform as head of state. But in fact General Musharraf's decision split the Commonwealth, with Britain urging a delay to allow the Pakistani president time to make good on his promises to organise "free and fair" elections in January, even though he argues that they should take place under the emergency regulations. Britain ensured that Pakistan was given some room to manoeuvre by getting the foreign ministers to agree that they would "review progress" by General Musharraf towards meeting the Commonwealth demands.

But there have been mutterings of "double standards" aimed at the British from the Africans whose leaders took off their military uniforms long ago. Pakistan was suspended for the first time when President Musharraf seized power in 1999, but was readmitted in 2004 on the promise that he would take off his uniform. We are still waiting.

Why is Britain sticking with the general?

Because he has been the partner of the US and Britain in the "war on terror" since 11 September 2001, although some thought has been given to a Plan B in the corridors of Whitehall for a while now.

Does Pakistan care about suspension?

Nobody likes being ejected from a club, and Pakistan is no different. President Musharraf in the run-up to the Commonwealth summit made a series of concessions and his government was pleading for a delay in the Commonwealth's decision. But apart from the stigma of barring countries from attending its meetings, the Commonwealth has no bite to its bark. It does not expel nations, nor does it impose economic sanctions on offenders.

What else will be discussed?

Climate change, global trade, education and poverty. Rwanda, which is one of only a handful of countries not to have been a British colony in the past, will be admitted as a new member. The Rwandans were so keen to join, they even learned to play cricket. Mr McKinnon's successor as secretary-general is due to be chosen. There are two main contenders, the Indian High Commissioner to London, Kamalesh Sharma, who has been travelling the globe to press his candidacy, and the Maltese Foreign Minister, Michael Frendo.

Malta hosted the last Commonwealth summit in 2005. It is being whispered that it is "Asia's turn" to lead the organisation, but a consensus needs to emerge around the winner. In the absence of that, the summiteers will vote on the next secretary-general this weekend.

Have the summits changed much?

Quite a bit, although Commonwealth leaders have met regularly for more than a century. Until the 1960s, even after the British Commonwealth was replaced by an association of "freely and equally associated states", they met in London.

But in recent decades, as different members have hosted the summits at the end of November on a biennial basis, the formula has remained pretty much the same, although the "retreat", invented by Pierre Trudeau of Canada, has been retreating because of the busy lives of the leaders. And in these days of round-the-clock news, the retreats have become less private.

The summits have often concluded with high-minded declarations – the most significant of which was the Harare Declaration in 1991 in which the members pledged anew their commitment to democracy, human rights and the rule of law. It was under that declar-ation in 1995 that the organisation set up its police arm, the Commonwealth Ministerial Action Group to monitor compliance, which is arguably the association's most important mechanism.

But more often than not, the summits are hijacked by a single issue – at the last meeting, in 2005, it was the world trade talks which were at a critical juncture. In 2003, it was the membership of Zimbabwe. In 1995, Nigeria was suspended during the Auckland summit after the execution of Ken Saro Wiwa and nine other Nigerian environmental activists while the Chogm was in session.

Any other memorable moments?

Presidents have lost their jobs in coups during Commonwealth summits, and the organisation came close to collapse in 1971 over a demand by the then British prime minister, Ted Heath, for the resumption of arms sales to South Africa. It must have been quite a sight to see Margaret Thatcher dancing with President Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia at the Lusaka summit. Or M Trudeau, the newly-elected Canadian prime minister, sliding down the banisters at Marlborough House during a London meeting. It seems that sometimes the leaders actually have fun.

Should the Commonwealth exist?

Yes...

* Any club that has 53 members and new ones queuing up to join must be worth saving

* It's a modern North-South grouping whose values and commitment to democracy have kept up with the times

* Abandoning the Commonwealth would leave an open goal for the French and La Francophonie (also 53 members)

No...

* It should come to a natural end when the Queen dies. Even Prince Charles has only shown a belated interest in the Commonwealth

* It's irrelevant and no longer appeals to younger generations

* The costly summits consume too many air miles and make the leaders look like lotus eaters at their luxury "retreats"

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies