The mysterious Monsieur Jacques: Behind the scenes of apartheid, French businessman Jean-Yves Ollivier was a shadowy broker for peace

As a new film explores his extraordinary influence in Africa, Francesca Steele meets an unlikely arbitrator

On an airstrip in Mozambique in September 1987, a genial Frenchman stood looking on from the sidelines as a prisoner exchange took place between several African nations more commonly seen at loggerheads than in successful negotiation.

The event involved the release of Du Toit, a high-profile South African officer who had been captured during a controversial operation in Angola two years before, as well as 133 Angolan soldiers and two anti-apartheid activists. It had taken seven months of difficult and often dangerous talks between South Africa, Angola, Mozambique and several other nations to reach this point. It was also, some observers later remarked, a key moment in the events and peace talks leading up to the release of Nelson Mandela and the dissolution of apartheid.

The mysterious Frenchman in question was Jean-Yves Ollivier, a key player in these negotiations and yet a man with no official political function whatsoever. Known to the South African secret service as "Monsieur Jacques", Ollivier, a successful commodities trader with an extensive contacts book including everyone from the Mitterrand family and Margaret Thatcher to several African presidents, had fashioned himself into a covert political arbitrator, spending hundreds of thousands of pounds of his own money flying back and forth between different nations, arranging unofficial parleys between leaders and, ultimately, securing the prisoner exchange on that hot September day in Maputo. Later, Ollivier would go on to become the only foreigner ever decorated both by the apartheid regime and then again under Nelson Mandela. But why had he got involved in the first place?

In the flesh, dressed in slacks a tad too short with eccentric green socks peeking out from underneath, Ollivier, who will be 70 years old later this year, is laid-back and equipped with an easy charm. He merrily recalls dangerous desert missions under the burning African sun from the comfort of his armchair at a lavish Mayfair hotel in rainy London. He is spending some time here to promote the documentary Plot for Peace, a film made by the African Oral History Archive, a not-for-profit foundation set up to safeguard African story-telling.

It was when Mandy Jacobson, Plot for Peace's producer and director, was rummaging through the organisation's video footage and photo archives that she came across various references to the mysterious "Monsieur Jacques", prompting her to track down Ollivier and persuade him to participate in a film. "Initially, he was reluctant," says Jacobson. "I think he had spent so long under the radar it was difficult to consider coming up above the parapet." Through the organisation's contacts, Jacobson also managed to persuade an illustrious line-up of former politicians and key figures to be interviewed, including Winnie Mandela, former South African President Thabo Mbeki, and the former President of Mozambique, Joaquim Chissano.

Plot for Peace is a serious, complex and rather extraordinary film, featuring grainy archived footage of the apartheid regime interspersed with original interviews, and a voiceover from Ollivier himself, who is presented with almost hesitant gravitas, as a shadowy figure playing cards alone in a darkened room. Several of the interviewees question Ollivier's motivation. "What he was looking for I'm not sure, because he never asked for money," says General Neels van Tonder, one-time head of South African Military Intelligence. Jacinto Veloso, a former Mozambique Security Minister, strongly implies that Ollivier hoped to gain indirectly from improved business conditions and contacts. And Odile Biyidi, president of Survie, a non-government organisation, insists that Ollivier was part of the French Secret Service.

Most of these suggestions seem plausible, in particular the last one, but Ollivier himself blithely dismisses them all. He was not a spy, he insists, and nor was he driven by an expectation of financial return, though he admits begrudgingly that a peaceful Africa – and a South Africa no longer under the trade sanctions of the 1980s – was certainly better for business. "Do you need a reason to stop when you are driving a car along the road and there is an accident ahead and you know that there are some people wounded?" he asks me. "Of course not. You stop your car. I felt that I had the means to help and that I had to do something. It was my duty as a human being."

The car crash that Ollivier feared was an ousting of the white South African community, a scenario that he wished to avoid for reasons personal as well as financial. Born in French Algeria – a "pied-noir" – he had been a teenager during the revolution, siding squarely with those who wanted to remain French. When Algeria became independent in 1962, Ollivier's family was forced out of the country. He rebelled and was incarcerated in Paris for five months, where he was "roughed up" by the French police and where he longed for the African continent that he had grown up in.

The experience had a profound effect. When in 1981, Ollivier went to South Africa on business, he foresaw a similar fate for this nation currently embroiled in racially motivated violence and widespread poverty. "I will never forget it," he says. "I put my first foot on the soil and immediately realised how wrong it was. I wanted to help apartheid die in peace."

What would have happened if he had not tried to help? "Look, apartheid was an insult to humanity. It was going to die anyway." But would that have happened less peacefully, without his own contribution? A Pinteresque pause. "Yes."

Ollivier is given to dramatic silences. A natural storyteller, he also utilises strategic displays of intimacy. "I'm going to tell you a little secret," he says in hushed tones, leaning in. "I was 13 when General de Gaulle came to Algeria, and I watched him say: 'This is your country, it will remain French and you can stay here.' We felt saved. And then he reneged on his words. I promised myself that I would never do that."

He has certainly found trustworthiness to be a valuable commodity. It was Ollivier's reliable track record as a businessman, along with incomparable networking abilities and friends in high places, that enabled him to broker the prisoner exchange, in which deals were cemented not with documents but with handshakes. "I always went along to meet a new contact accompanied by someone who already knew and trusted me," he explains. "That way, if someone didn't know quite who I was, they could depend on the faith they had in that person standing next to me."

Here, after all, was a continent beset by mistrust. Official deals often had little impact and were regarded with derision; along with trying to combat the African National Congress, which it viewed as a terrorist organisation, the South African government was also trying desperately to curb Soviet expansion in places such as Angola, where Cuban troops were stationed. The Reagan administration had adopted a heavily criticised, less hostile approach to South Africa known as "constructive engagement", to ward off Marxist revolutionaries, but the talks were still largely bilateral.

The success of the prisoner exchange buoyed confidence between nations. Ollivier and his good friend Jean-Christophe Mitterrand, the son of Francois Mitterrand, persuaded representatives from South Africa, Mozambique and Angola to attend informal talks in the Kalahari desert, where they put together the basis for the 1988 Brazzaville Protocol, an agreement that mandated the withdrawal of Cuban troops from Angola and the independence of South Africa-occupied Namibia. Soon after, apartheid hardliner PW Botha resigned as President of South Africa.

"I'll tell you a little something," whispers Ollivier. "I don't think it would have been possible without US policy to achieve Brazzaville. But at the same time, I don't think that official policy would have worked without trust between the different parties. And I was instrumental in that."

Is Ollivier overstating his claim? Stephen Smith, the scriptwriter and historical consultant on Plot for Peace and a former Africa editor at Le Monde, does not think so, although he does not necessarily approve of Ollivier's modus operandi either. "Why have secret services if, when it comes to the crunch, you use businessmen... to approach adversaries?" Smith says. "We all know how powerful interpreters are. They tweak messages the way they want and are difficult, if not impossible, to control. I hope the film makes this as clear as the advantages of bypassing institutionalised channels." The film's producers say they chose Smith precisely because of his reservations about the clandestine nature of Ollivier's involvement, to better substantiate its claims.

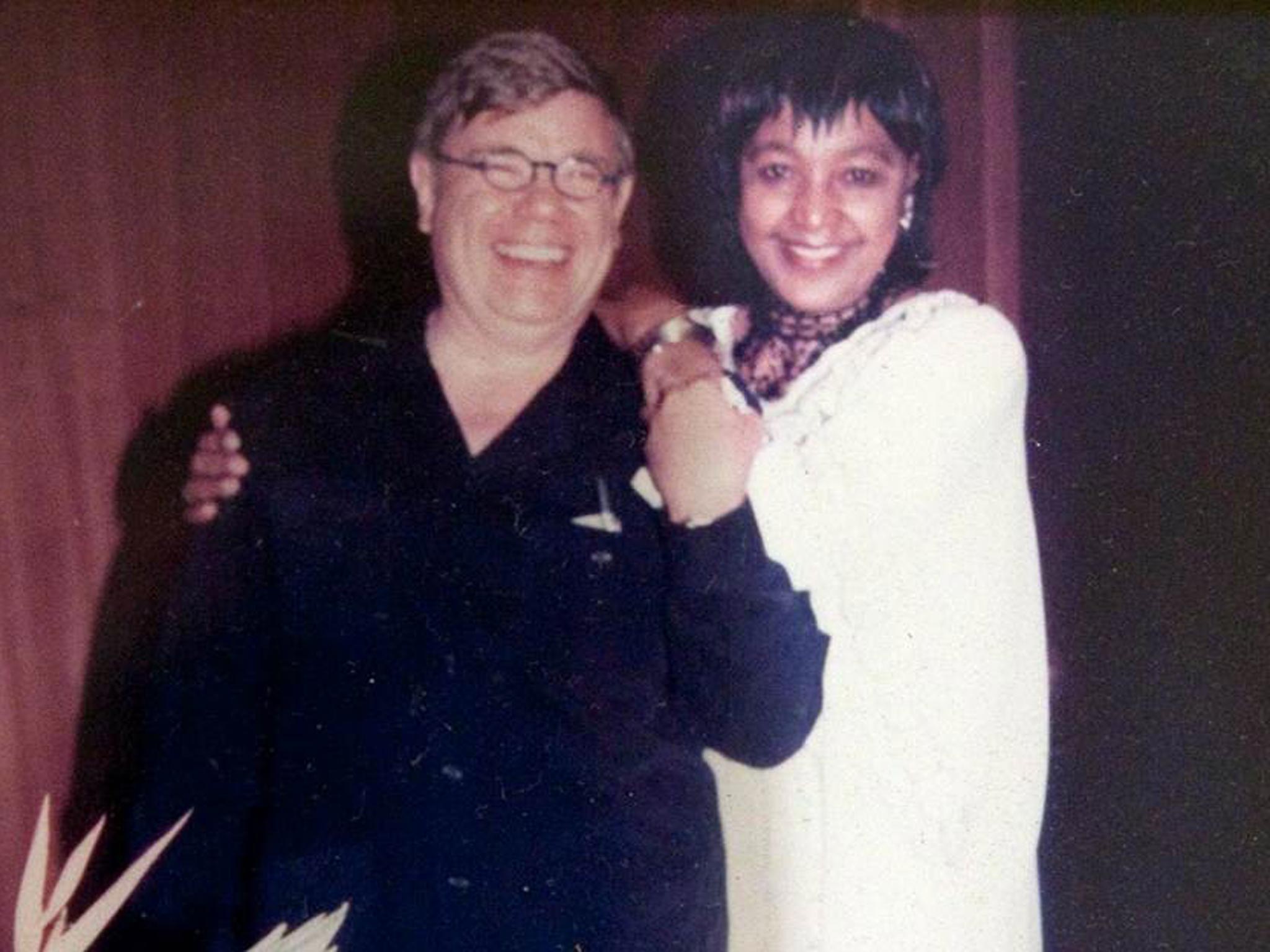

Either way, it has all worked out rather well for Ollivier. He became great friends with Winnie Mandela, and met the late Nelson Mandela on several occasions ("He left this planet sadly without seeing his dream fully realised," Ollivier tells me). He is also clearly still a man of substantial means, with six houses, two of which are in South Africa. He insists that the only money he was ever given during his political dealings was about £50,000 by the South Africa government "to cover some expenses".

Along with the documentary, Ollivier has a book out now in France – Ni Vu, Ni Connu – De Chirac et Foccart à Mandela. Ma vie de négociant en politique ("Neither Seen, Nor Heard – My Life as a political broker from Chirac and Foccart to Mandela"), as well as a website on which he blogs extensively. Why the sudden transformation from voluntary anonymity to mass exposure? It seems odd when discretion was once his main currency. The film's producers say that he has simply "embraced" talking about his contribution to history.

Still, one can't help but feel that "Monsieur Jacques" still has a trick or two up his sleeve – another business venture perhaps (he still runs businesses investing in infrastructure projects around the world) or a covert political operation of some kind. It is a sense of mystery that he seems keen to bolster as he flits coolly between candor and elusiveness.

What job do his official papers say he does now then? "Ah, well, my passport says I am retired," he says, winking mischievously. "But that's a lie."

'Plot for Peace' is released in UK cinemas today

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments