The tree of life (and its super fruit)

The medicinal properties of the baobab fruit are the stuff of African legend. Claire Soares says it also tastes great and, thanks to an EU ruling, we will all be able to try some soon

It didn't matter what was wrong with me, be it a stomach upset or a rogue spot, the remedy prescribed by Senegalese friends was always the same. Baobab fruit – and lots of it.

Usually it was administered in the form of a Senegalese smoothie, the fruit pulp mixed with water to make what is known in the local Wolof language as bouye. The white drink delivered hints of velvety yoghurt with a flick of tart sherbet to the tongue. And it was not only mighty tasty, it left Western anti-diarrhoea fixes, such as Imodium, lagging and was soon an ever-present item in my fridge.

The baobab fruit has three times as much vitamin C as an orange, 50 per cent more calcium than spinach and is a plentiful source of anti-oxidants, those disease-fighting molecules credited with helping reduce the risk of everything from cancer to heart disease. Until recently, this super-fruit was off limits to British consumers, unless they fancied a shopping trip to Africa. But now the baobab fruit has won approval from EU food regulators, expect it to be winging its way to a supermarket shelf near you.

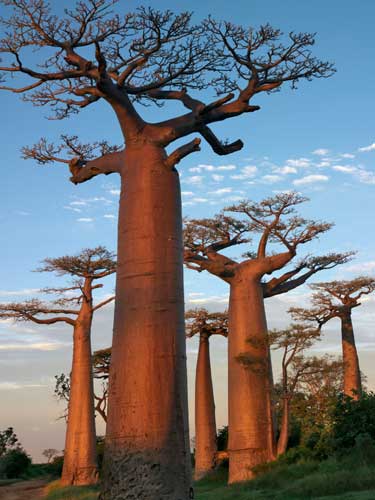

The baobab tree is an integral part of the African landscape. Nicknamed the "upside-down tree", it looks like it has been planted on its head, with its roots sticking up into the air to produce a somewhat eerie silhouette.

Bush legends about the baobab abound. One has it that the god Thora took a dislike to the baobab growing in his garden and promptly chucked it over the wall of paradise; it landed below on earth, upside down but still alive, and continued to grow. In another popular myth, the gods get so irritated by the vanity of the baobab, as it tosses it branches, flicks its flowers and brags to other creatures about its superlative beauty, that they uproot it and upend it to teach it a lesson in humility.

Today, many Africans refer to it as the "Tree of Life", and it's not hard to see why. With a trunk that can grow up to 15m in circumference, a single tree can hold up to 4,500 litres of water. Fibres from the bark can be turned into rope and cloth; fresh leaves are often eaten to boost the immune system; and some hollowed-out trunks have been used to provide shelter for as many as 40 people. And then, of course, there's the fruit.

In Senegal – where the tree is such a part of the national psyche that it has given its name to one of the country's most successful bands Orchestre Baobab – the idea of Europe suddenly discovering the plant amuses many.

But the scale of Europe's appetite for the unusual fruit – with its hard nut-like shell and white, powdery pulp – could play a crucial role in improving the lives of millions of people across rural Africa. People such as Andrew Mbaimbai, a fruit harvester in Malawi.

He and his family collect the gourd-like fruit – which dangles from the branches on long stems and resembles sleeping bats from a distance – along the shores of Lake Malawi, and he has been able to pay for schooling for his 15- and 18-year-old daughters with the income. "It's very good news. We are still improving all the time, and I hope that we will have even bigger demand now and I might even be able to employ someone," Mr Mbaimbai said.

A recent report by the UK-based Natural Resources Institute estimated that the trade in baobab fruit could be worth up to $1bn (£500m) a year for African producers, employing more than 2.5 million households across the continent.

However, before that could even begin to happen, the baobab needed to extend its reach beyond Africa and the key to that was winning what is known as Novel Foods approval from the European Union.

Since 1997, foods not commonly eaten in the EU have had to be formally sanctioned before going on sale. The baobab charge was led by the non-profit group PhytoTrade based in Johannesburg, which spent two years and more than £150,000 lobbying Brussels. This month they finally saw the fruits of their labour.

"This approval unlocks massive opportunities for the very poorest rural communities where there aren't many income-generating options," said PhytoTrade's chief executive Gus Le Breton. "We already have a couple of hundred tonnes of baobab fruit pulp that has been sitting in warehouses for the last year, just waiting for this moment."

According to Mr Le Breton, the first baobab pulp could be in UK shops in less than three months. In the next year, he expects to see major juice and smoothie companies rolling out their own baobab lines. Cereal bars, biscuits and confectionery are other areas ripe for development.

And the euphoria is stretching across the continent from Lilongwe to Dakar. "We're delighted, what better news could there be?" said Chris Dohse, the general manager of TreeCrops in the Malawian capital. Oumar Dieme of Food Technology Institute in Senegal agreed: "It's great news for us. We hope we can profit from all the baobab trees across Senegal."

One advantage to baobab harvesting is that there is no need for fancy start-up equipment. All you need is a pair of hands. And because the baobab is an indigenous plant, better placed to survive in arid climes, it is not expected to be as vulnerable to the ravages of climate change that Africa is expected to have to endure over the coming years. Earning an income from the vegetation already in place also provides an incentive to rural communities not to rip up established plants in favour of whichever cash crop is in vogue and hence preserve the soil structure, according to some agriculture experts.

However, there are fears about making Africa's resource sustainable, especially if demand rockets in Europe. "We're blessed with baobab trees, but if this fruit becomes Africa's apple and goes global, which I believe it will, then we need to plant more trees," said Mr Dohse of TreeCrops. "And we need to start now."

And the worry of not enough baobab fruit to go round is shared by ordinary Africans too.

"We've been eating the fruit for years. I grew up on it, so did my ancestors," said a Dakar resident, Marie Manga, "and although I'm glad the Europeans are going to get to try it, I do hope they leave some for us."

African superfruits

Marula

Callled the elephant fruit, this round yellowy-green specimen looks like it could be a close relative of the plum. The flesh has eight times more vitamin C than an orange, and the nut is also rich in minerals. It is already the base for the South African liqueur Amarula, and according to PhytoTrade is set to be "one of the next big ones".

Mongongo

Native to Zambia, Botswana, Namibia, the mongongo is rich in vitamin E. The dry fruit is often steamed first to soften the skin. Once the husk is removed, the edible red pulp can be used in jams and porridge, while the inner nut can be roasted or pressed for oil. Some people prefer to let elephants do the shelling – the nuts can pass whole through the animal's digestive tract and be collected from the dung.

Myths and medicine

* The trees are native to Africa but are also found in Australia and India.

* Baobabs can grow up to 30m high and their trunks can be up to 15m around. One ancient tree in Zimbabwe is so large that 40 people can shelter inside. Others have been turned into shops, prisons, bus shelters and bars.

* The trees are very difficult to kill. If stripped of their bark, they simply form new bark and carry on growing. Carbon dating has found some specimens to be at least 3,000 years old. When they die, they rot from the inside and suddenly collapse.

* The trunk can store thousands of litres of water and elephants have been known to tear them apart to get to the moist wood.

* The gourd-like fruits, above, which are six to eight inches long, hang by long stems off the branch.

* Some people believe that if you pick a flower from a baobab tree you will be eaten by a lion. But if you eat water in which baobab seeds have been soaked, you will be safe from a crocodile attack.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks