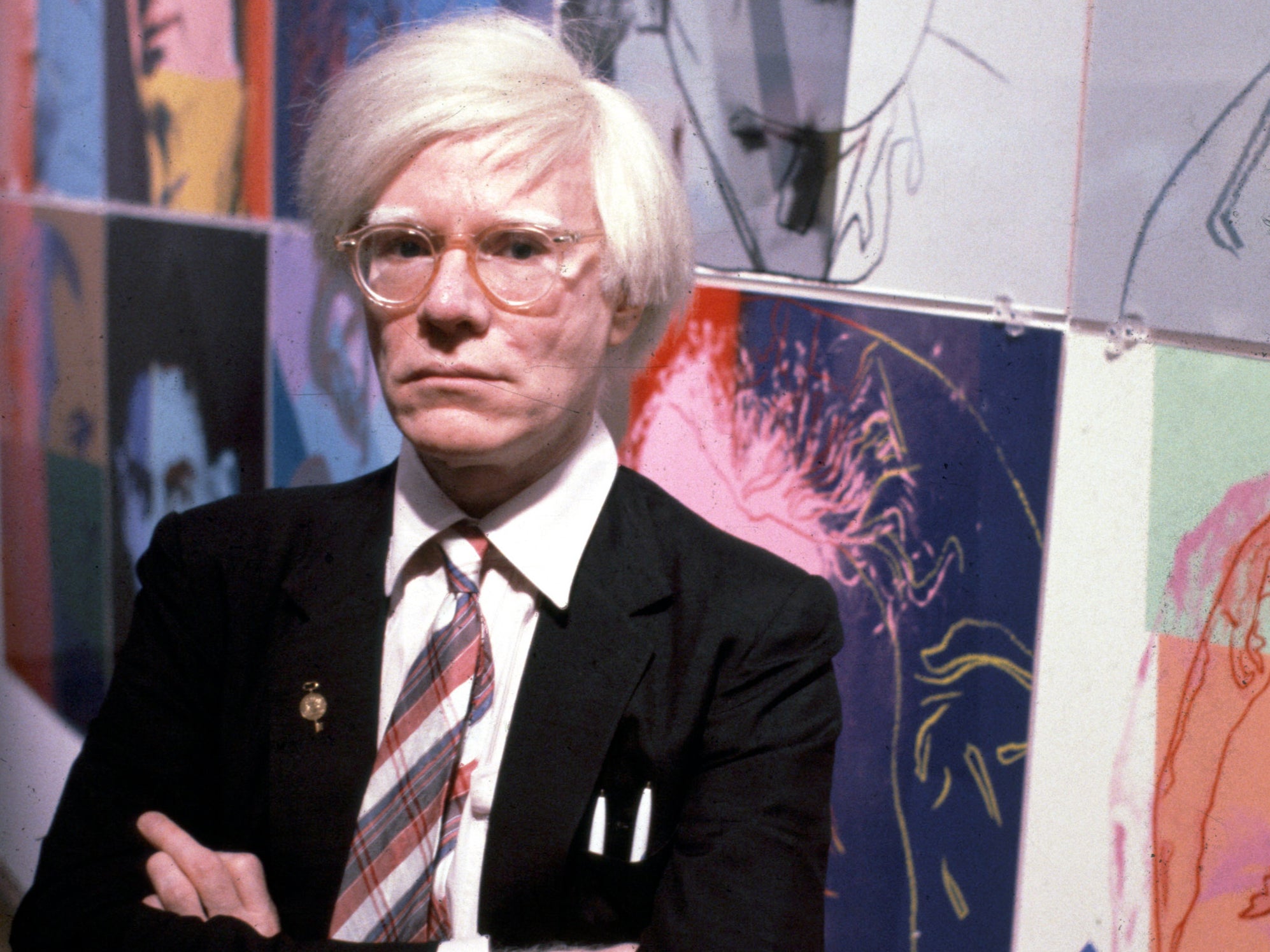

A Prince photograph, Andy Warhol, and the Supreme Court battle that put pop art on trial

Photographer Lynn Goldsmith contends Warhol infringed on her copyright when he used one of her images in several works; the Warhol Foundation insists it was fair. Clémence Michallon looks into the case that has reached the highest court in the land

One day in 1981, Prince Rogers Nelson, wearing a high-collared white button-down shirt, black pants, and suspenders, gazed straight into the lens of Lynn Goldsmith’s camera. He was on his way to superstardom, three years away from the colossal success of Purple Rain. Goldsmith, a court filing would later state, was on assignment for Newsweek. She worked with the lighting to emphasize the artist’s bone structure. She applied eyeshadow and lip gloss on him. She aimed to capture his “willing[ness] to bust through what must be [his] immense fears to make the work that [he] wanted to [make].” She took a series of black-and-white shots using a Nikon 35-mm camera.

Prince, Goldsmith would later recall, seemed nervous and uncomfortable, and left the shoot before she could take additional photos. She came out of the session with 23 images – 11 in color and 12 in black and white. Among the black-and-white photos was the image which, 40 years later, would become the center of a lengthy legal battle, rising all the way to the Supreme Court.

Back in the Eighties, Andy Warhol used the photo in several artworks, transforming it similarly to images Marilyn Monroe, Elvis Presley, and Mao Zedong he used in other works. It was Andy Warhol’s estate, not Goldsmith, who first took legal action by suing the photographer in April 2017. The suit, filed in New York, asked a court to declare that Warhol’s Prince artworks are protected from litigation and that they do not infringe upon Goldsmith’s copyright. It made its way through the lower courts, first in the Southern District of New York, and then in the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit.

On Monday (28 March), the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case. It will determine whether Warhol infringed Goldsmith’s copyright when using her photo, or whether he transformed the image to such a degree that it’s essentially immune from copyright claims.

Goldsmith is a prominent photographer whose subjects have included some of the world’s most famous musicians. Her work has been featured on more than 100 album covers. (The ethereal photo on the cover of Patti Smith’s Easter? That was her.) Bob Marley, Kiss, Miles Davis, and many, many more have graced her catalog. According to the appeals court, she first licensed her photo of Prince to Vanity Fair in 1984 through an agency.

“The license permitted Vanity Fair to publish an illustration based on [the photograph in question] in its November 1984 issue, once as a full page and once as a quarter page,” the court of appeals wrote. “The license further required that the illustration be accompanied by an attribution to Goldsmith. Goldsmith was unaware of the license at the time and played no role in selecting the Goldsmith Photograph for submission to Vanity Fair.”

Vanity Fair commissioned Warhol to create an artwork for a piece on Prince. It ran in November 1984 with the headline “Purple Fame” and an attribution to Goldsmith, per the appeals court. Warhol’s artwork for Vanity Fair used Goldsmith’s photo, adding color to it and transforming it in several ways.

Warhol created several more artworks based on Goldsmith’s photo, producing 16 images in total. These have become collectively known as the Prince Series.

According to the court of appeals, Goldsmith didn’t know about the Prince Series until 2016. Following Prince’s death that year, Condé Nast, the media company behind Vanity Fair, put together a special commemorative magazine using an image from the Prince Series on its cover. “It was at this point that Goldsmith first became aware of the Prince Series,” the court of appeals wrote. “In late July 2016, Goldsmith contacted [the Andy Warhol Foundation] to advise it of the perceived infringement of her copyright.” (The foundation argued in its own, original filing that the Prince Series had been “widely published throughout the United States.”)

The Andy Warhol Foundation filed its lawsuit against Goldsmith on 7 April 2017, asking for a declaratory judgment that the Prince Series doesn’t violate the photographer’s copyright, or that it is protected by a doctrine known as fair use. (Fair use, per the US Copyright Office, “promotes freedom of expression by permitting the unlicensed use of copyright-protected works in certain circumstances.”) According to the court of appeals, Goldsmith countersued for alleged copyright infringement.

In July 2019, the district court ruled in favor of the Andy Warhol Foundation. It argued in part that the Prince Series was “transformative”, a key concept when trying to argue fair use. Per the US Copyright Office, “transformative” uses – which “add something new, with a further purpose or different character, and do not substitute for the original use of the work” are “more likely to be considered fair.” For the district court, Goldsmith’s photo portrayed Prince as “a vulnerable human being” and “not a comfortable person”, while Warhol’s work “can reasonably be perceived to reflect the opposite”, presenting him as “an iconic, larger-than-life figure.”

Out of the four factors typically weighed to judge whether fair use should apply to a dispute, the district court that three were in favor of the Andy Warhol Foundation, and one was “neutral”. It therefore granted the foundation’s request for a summary judgment.

But the court of appeals disagreed. On 26 March 2021, it reversed the district court’s decision and remanded the case for further proceedings. While it admitted that “it may well have been Goldsmith’s subjective intent to portray Prince as a ‘vulnerable human being’ and Warhol’s to strip Prince of that humanity and instead display him as a popular icon”, it found that whether a work is transformative shouldn’t be judged on the perceived intent behind that work.

“The district judge should not assume the role of art critic and seek to ascertain the intent behind or meaning of the works at issue,” it added. “That is so both because judges are typically unsuited to make aesthetic judgments and because such perceptions are inherently subjective.”

On Monday (28 March), the Supreme Court announced it had agreed to hear the case. It’s a relatively rare decision: the court generally doesn’t have an obligation to hear a case, and according to its own numbers, it usually takes on between 100 and 150 of the more than 7,000 cases it is asked to review each year.

Roman Martinez, an attorney for the Andy Warhol Foundation, told Reuters he welcomed the Supreme Court’s decision to hear the case and hopes it will “recognize that Andy Warhol’s transformative works of art are fully protected by law.”

Goldsmith celebrated the Supreme Court’s decision in an Instagram post which read in part: “I fought [the Andy Warhol Foundation’s suit] to protect not only my own rights, but the rights of all photographers and visual artists to make a living by licensing their creative work – and also to decide when, how, and even whether to exploit their creative works or license others to do so. I look forward to continuing that fight in the Supreme Court.”

In a follow-up post, she added: “Photographers work very hard, often with great physical and material cost to create imagery. They should have the right to determine if others can use what they create for their own purposes or to change it in any way. Permission should be asked.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.