The man, the myth: In public, JFK was the emblem of a shining new age. In private, he was a drug-taking philanderer with Mob links

To the public, he was the ultimate emblem of a shining new age. In private, he was a drug-taking philanderer with Mob links. In the week of the 50th anniversary of John F Kennedy's assassination, Professor Mark White salutes the president of spin

Even before his assassination, John F Kennedy was an iconic figure for many Americans. Young, dashing, charismatic, he promised a brighter future for America. It seemed that he had achieved much in his two years and 10 months in the White House: defusing the Cold War crises over Berlin and Cuba, defining civil rights as a national objective and introducing the Peace Corps.

Public opinion polls show that the American people consistently rate Kennedy as one of the greatest leaders in US history, secure in the presidential pantheon alongside Abraham Lincoln and Franklin Roosevelt.

It is probably sobering to the public, on both sides of the Atlantic, to learn that many historians view Kennedy differently. In polls of academics, Kennedy tends to be rated merely as an "above-average" president. He is consistently rated below Harry Truman, for example. This more critical view is due to the fact that since the 1970s, a different narrative of the Kennedy years has emerged. He failed to secure the passage in Congress of his Bills on education, healthcare for the aged and civil rights.

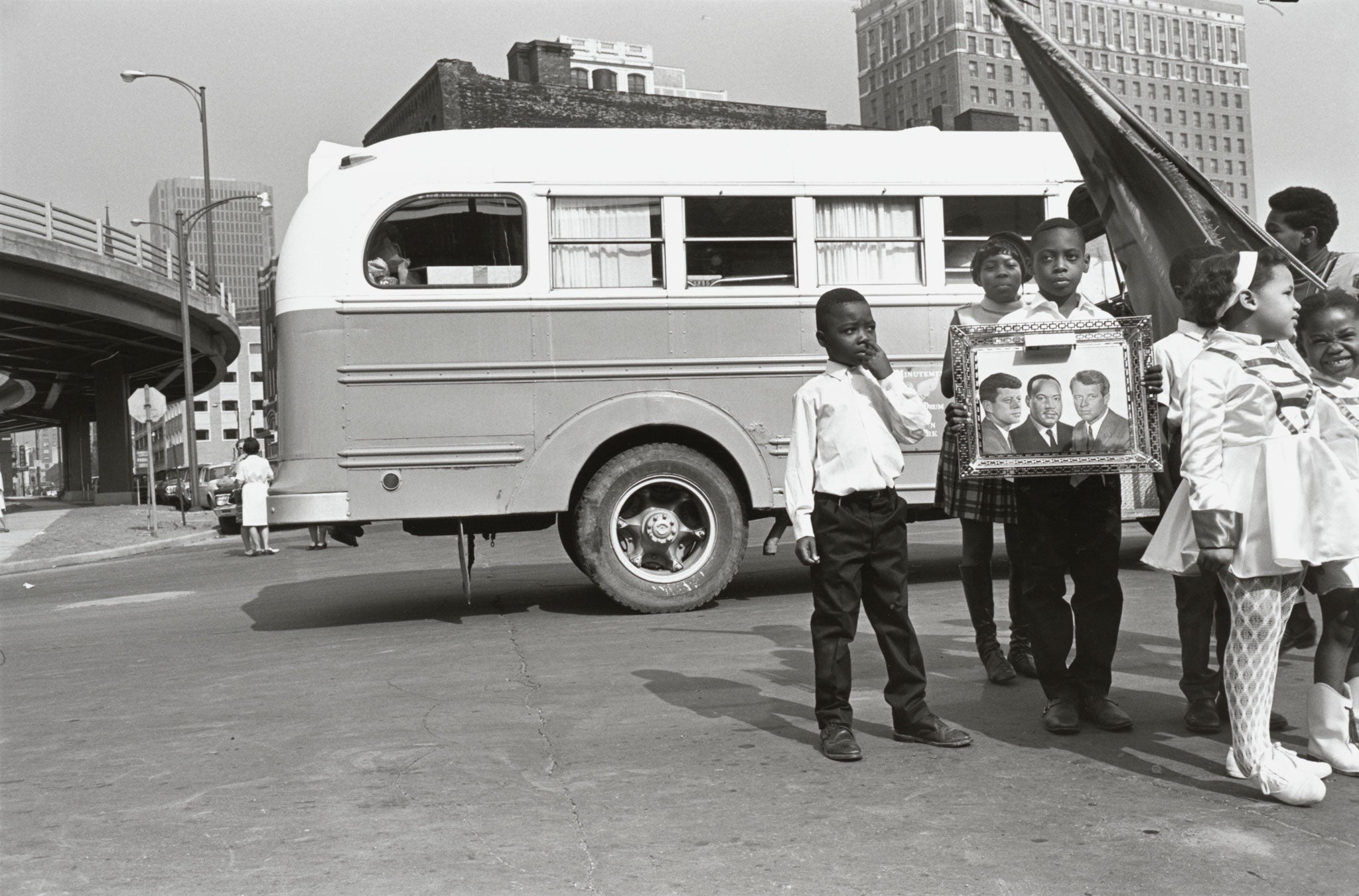

Despite being venerated by many African-Americans, the passage of his civil-rights Bill to end racial segregation in the South required Lyndon Johnson's genius for persuading Congress to do his bidding. In addition, Kennedy authorised the Bay of Pigs invasion, the failed attempt to use Cuban émigrés to trigger an anti-Castro uprising. And he escalated involvement in Vietnam, increasing the number of US military personnel there from around 800 to more than 16,000.

So why is it, then, that so many Americans still admire Kennedy? The answer is in part the tragedy of his death – a young president cut down by a terrible act of violence – and an accompanying need to remember him well. But the continuing reverence for Kennedy is due more fundamentally to the power of his image constructed during his lifetime.

No leader on either side of the Atlantic has since come close to the idolatry generated by Kennedy. Barack Obama inspired people with a similar message of hope for a short while in 2008, but it faded quickly. In Britain, Tony Blair's popularity was broad but not so deep-rooted. In Russia, Vladimir Putin seems a crude pastiche of the leader as hero. But with Kennedy, image creation has proven to be a genuine and long-lasting achievement.

It is the multi-faceted nature of Kennedy's image that accounts for its power. In the two decades before he ran for president he established, with the help of his father Joseph P Kennedy, a number of ideas about himself in the public mind.

The publication in 1940 of his first book, Why England Slept, a reworking of his Harvard undergraduate thesis on the British appeasement of Germany, suggested he was a man of letters, a notion furthered by the release in 1956 of his second book, Profiles in Courage, which won a Pulitzer Prize (despite, as we now know, the book being largely the work of others). His courageous conduct in responding to the ramming of his PT boat by a Japanese destroyer in the Second World War was widely reported, led to military honours, and created the idea of Kennedy as a war hero.

His election while still in his twenties to the House of Representatives and to the Senate at the age of 35 suggested he was an exceptionally precocious politician. The publicity given to his large and interesting family, increased by his marriage in 1953 to Jacqueline Bouvier, built up an image of JFK as a symbol of the family – not just an ordinary politician but a representative of a dynasty. And his youthful good looks made him a sex symbol; this was something that was noticed as early as 1946, when he campaigned for Congress.

The 1960 presidential campaign and his inauguration added two further ideas. The campaign issue created by the fact that no Catholic had ever been elected president was a political problem for Kennedy, but it resulted in him being viewed as a man of faith. The pageantry of his inauguration, as well as Jackie's princess-like appearance, helped create the idea of Kennedy as royal – and of the Kennedys as America's royal family.

As president, the media attention given to his wife, children and his brother Robert as attorney general strengthened the idea of JFK as a familial symbol. Marilyn Monroe singing "Happy Birthday" for him at Madison Square Garden in New York augmented his own erotic credentials – the greatest sex symbol of the age performing for his enjoyment. The famous White House events organised by Jackie Kennedy, such as the concert given by cellist Pablo Casals, enlarged the idea of Kennedy as a man of letters and cultural refinement.

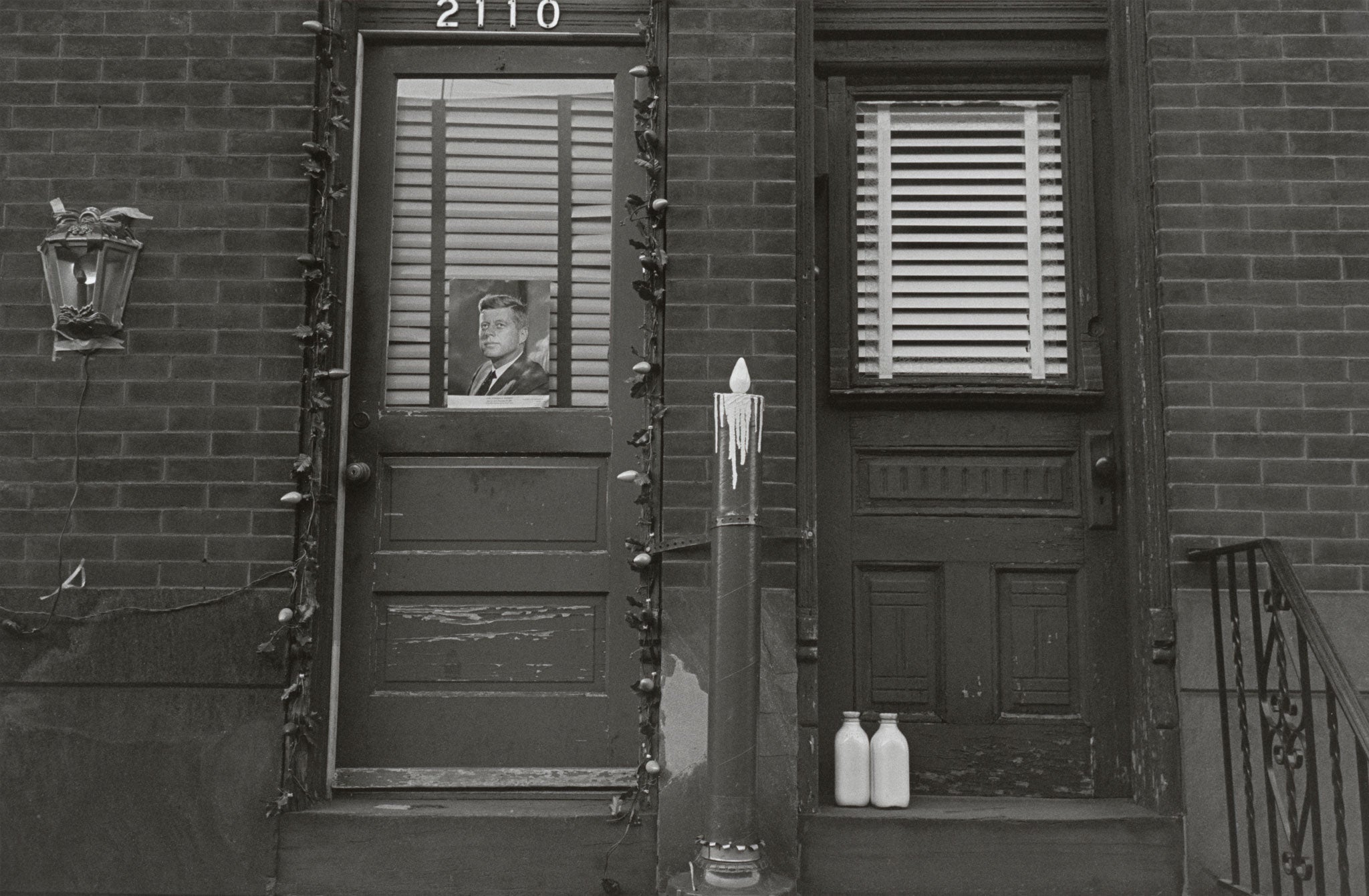

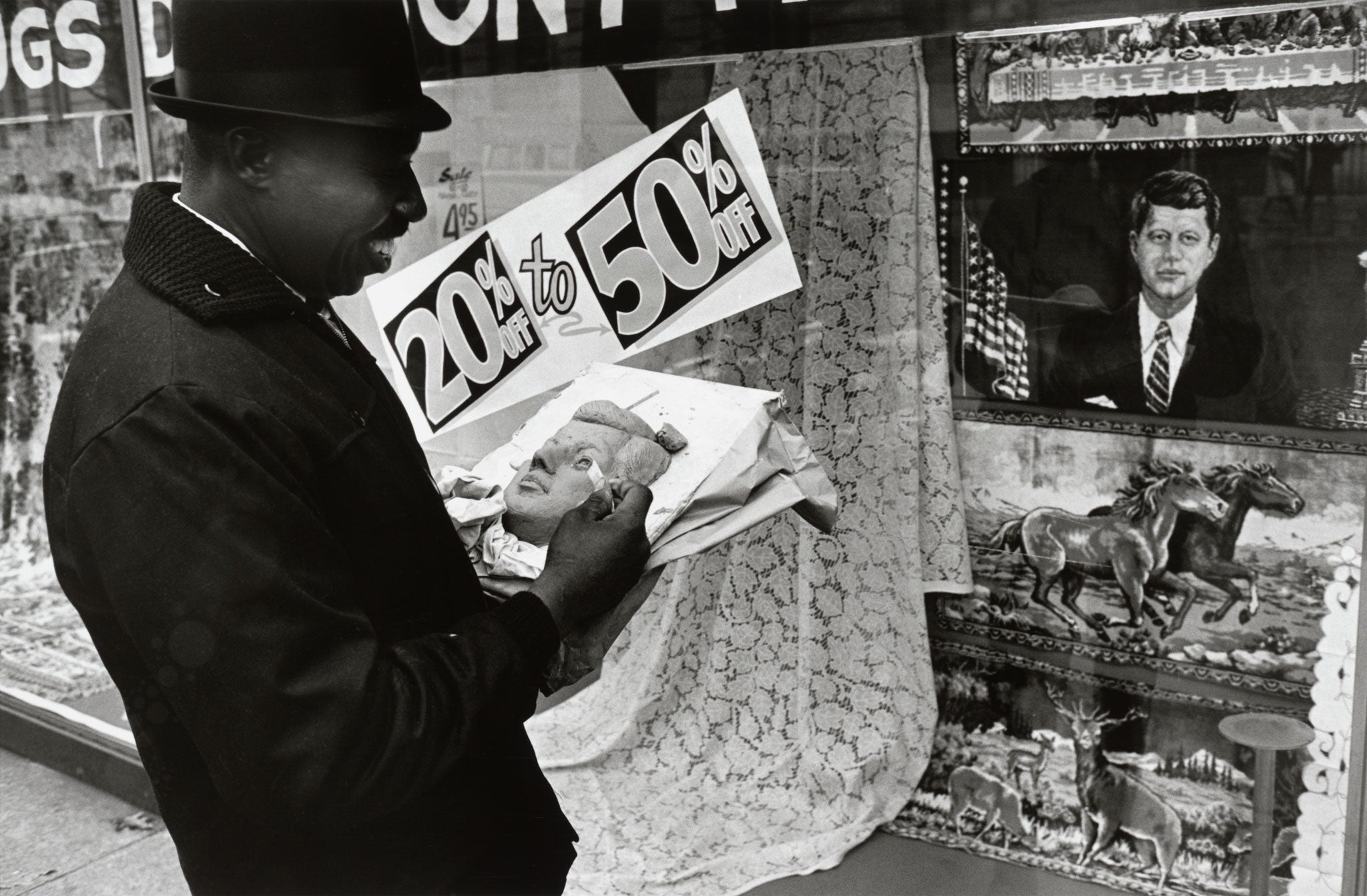

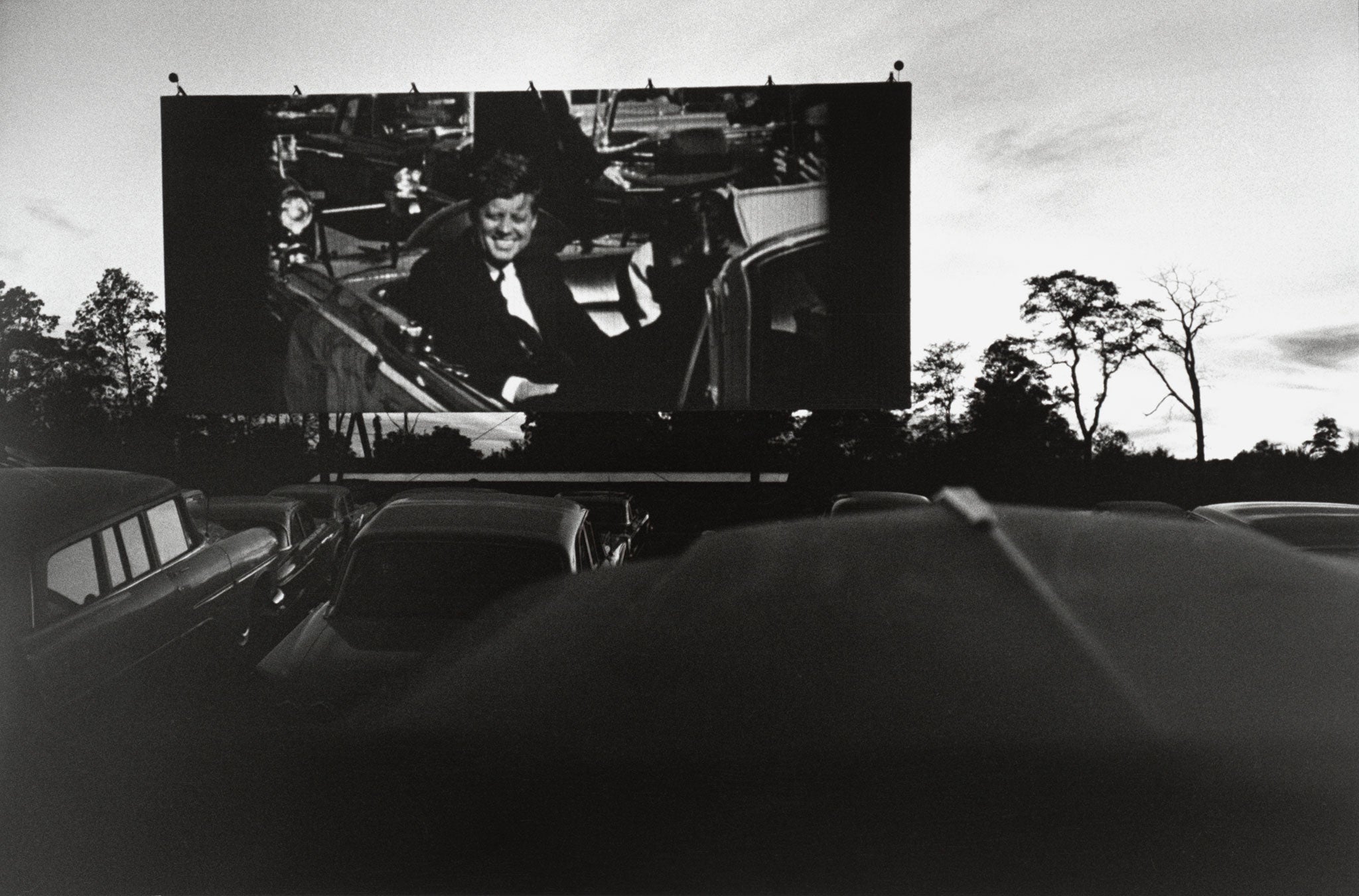

The popular sainthood that Kennedy has posthumously enjoyed, which Lee Friedlander's photographs capture so strikingly, was due, then, not only to the sense of tragic loss felt by Americans after his assassination, but to the potency of his image during his lifetime.

There was one other crucial factor: the role played by Jackie Kennedy. Despite the horror of her husband's murder – most likely perpetrated by Lee Harvey Oswald alone, despite the plethora of conspiracy theories – she was able to focus on how Americans would remember her husband. Worried that scholars would judge his presidency harshly, she sought to use myth to counter history. She decided, therefore, that the funeral would be based on Lincoln's, thereby asserting Kennedy's greatness and martyrdom by associating him with a president who was both great and a martyr.

Most importantly, in an interview with the journalist Theodore White for Life magazine only a week after Dallas, she discussed her late husband's penchant for the musical Camelot. What she implied was that JFK's leadership had been so graceful and inspiring it evoked the story of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table.

With this article, Jackie had given the Kennedy legend a name: Camelot. And in the battle between the former first lady and later revisionist historians over how JFK was to be remembered, Jackie – unquestionably – won.

Since the 1970s, a series of revelations about Kennedy's personal life have threatened to tarnish his lofty reputation. These have included the fact that he was a philanderer of spectacular proportions, had taken drugs and had alleged dealings with the Mob. These are not trivial matters. Potentially they could have destroyed his presidency.

For example, had his affairs with Judith Campbell (who was also seeing Chicago crime boss Sam Giancana) or Ellen Rometsch (who had been a member of Communist Party organisations in East Germany) come to light, he could have been impeached; today, he certainly would be.

But these personal revelations have failed to diminish the American people's adoration for Kennedy, as public-opinion polls make clear. This is because sex appeal was a major part of his image during his lifetime. So although shocking, the revelations about his Don Juan conduct in private are consistent with the pre-1963 idea of JFK as an erotic symbol.

Kennedy succeeded in constructing an image of himself as a war hero, a man of letters, a sex symbol, a family man of religious conviction, and a political prodigy with a royal sensibility. Kennedy appeared to be all these things; and as his record as a policy-maker and a man is clearly mixed, it is this dazzling image that continues to fascinate us.

Mark White, professor of history at Queen Mary, University of London, is the author of several books on JFK, including 'Kennedy: A Cultural History of an American Icon' (£18.99, Bloomsbury). 'JFK: A Photographic Memoir' by Lee Friedlander is published by Yale University Press, priced £35

All pictures: Gelatin silver print. Yale University Art Gallery. © Lee Friedlander, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments