Luxury gap: how Japan turned into a nation of the haves and the have-nots

It used to be described as a nation of 100 million middle-class people. But the <i>nouveau riche</i> have taken to flaunting their wealth – while the rest of society prepares for a recession. By David McNeill

In a planet slowly cooking in greenhouse gases, it is one of the more depressing urban sights: a 2.9 tonne, petrol-guzzling monster inching down some of the narrowest, busiest streets in Asia. Long the preferred transport accessory of US hip-hoppers and young corporate titans, the Hummer can increasingly be seen trundling through the hipper districts of Tokyo, being waved away from car parks built for family Toyotas and Nissans.

Some of the newer Hummers are nine-mile-per-gallon bling on wheels, sporting fur seats, dashboard Bulgari clocks and crystal-studded steering columns.

Not long ago, such conspicuous displays of wealth were frowned on in Japan, which revelled in its reputation as one of the most egalitarian developed countries in the world. Bulky American cars were once the preserve of rich dentists and Yakuza gangsters, while bosses were ferried through Tokyo in discreet black Toyota limousines. The rich often opted for high-end but low-key German cars during the so-called bubble-era of the late 1980s, when soaring land and stock prices fuelled a now infamous consumption boom. Now, it seems, the good times are back... at least for some.

Despite a looming recession, declining stock market and Japan's inexorable long-term economic slide, the glitzier shopping districts of Asia's richest metropolis are booming. In Ginza, the Italian jewellery brand Bulgari has just opened its biggest store, a 10-floor, 940 sq m behemoth called Bulgari Tower, complete with Roman-style marble walls and eye-watering price-tags. It was the firm's second Tokyo opening in a year. Armani and Gucci have also just set up huge stores in Japan, which is now the world's top market for many designer brands. The HSBC bank recently estimated that up to 45 per cent of luxury goods are sold here.

Tokyo is also the planet's culinary capital, according to the famed Michelin Guide, which last November gave 150 restaurants in the city a total of 191 stars, relegating Paris to a distant second with 94 and New York an embarrassing third with 54. London scored just 50.

"Tokyo has become the world leader in gourmet dining," the guide announced.

The world's most expensive restaurant, says the New York-based guide Zagat Survey, is the Aragawa steakhouse in Shimbashi, Tokyo, where the menu starts at 70,000 yen (£330); a bottle of wine can set you back 160,000 yen (£750) and an empty table is rarer than a swallow in winter. Hummer Japan will ferry you there in its 10m stretch limousine: a snip at 300,000 yen (£1,400) a night. The company recently added another limousine to its line-up. "Business is good," said a spokesman.

After years of dire predictions for the fate of the world's second largest economy, some consider the emergence of a new generation of nouveau riche a healthy sign. But politicians are increasingly being forced to admit the unthinkable in a nation that once coined an expression roughly translated as "100 million middle-class people" – Japan is becoming a two-tiered society.

"We are being divided into rich people and poor people," the Social Democrat opposition leader Mizuho Fukushima recently told the Japanese media. "And the gap is widening."

Even the Imperial Family, long a model of frugality compared to their spendthrift European counterparts, is not immune: Princess Masako is under fire in the tabloid press for her splashy consumption.

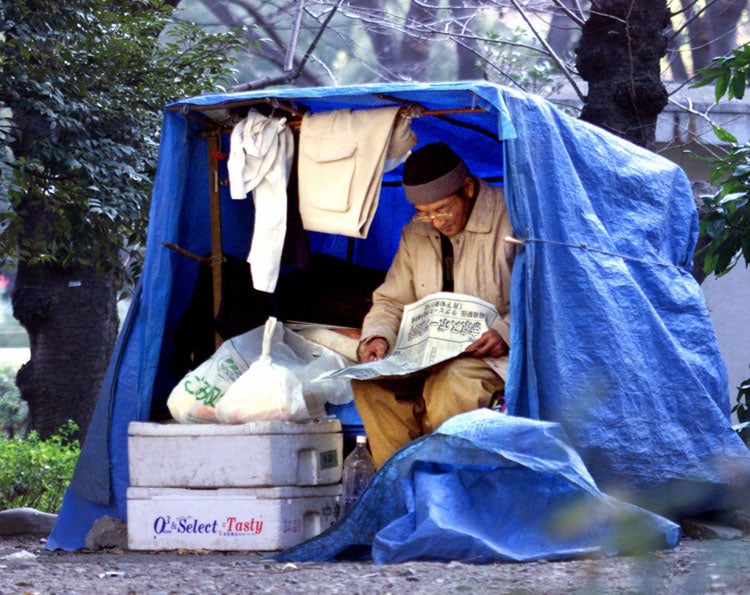

The fear that Japan is entering an era of what the TV pundit Takuro Morinaga calls "dog-eat-dog US-style capitalism" is belied by Tokyo's orderly, slum-free streets. But the trend has been explored in a slew of books that have popularised the phrase "kakusa shakai," literally meaning "gap society". Morinaga's bestselling book on the vanishing middle class gives readers tips on how to survive on an annual income of less than three million yen (£14,000). He now admits he may have been too optimistic: two million yen (£9,300) has become the de-facto poverty line for millions of Japanese, especially outside the capital.

A quarter of the population is defaulting on national pension payments and the number of households receiving social security topped one million last year, swelled by the growing ranks of poor elderly people. More than one-third of the workforce is part-time as many companies wave goodbye to the famed Japanese lifetime employment system, nudged along by government legislation, which abolished restrictions on flexible hiring a few years ago. Huge temp agencies have stepped in to fill the employment gap, and widen the class divide.

An annual lifestyle survey by the Cabinet Office found that the share of Japanese who believe they are middle class has fallen to just over half of the population, down from a peak of 61.3 per cent in 1973.

The so-called new poor briefly came under the national spotlight recently when three people in western Japan died of starvation after being refused social benefits. One man, found dead and alone in his tiny apartment, left behind a diary detailing his craving for a 100-yen (50p) rice ball. While that was an extreme case, many people say they are living on the breadline.

"I feel that I can't afford to go to the doctor or take off a day," says Noboru Sugawara, one of over four million "freeters" or young people surviving on part-time work. He lives in a flat with no bath and earns 1,000 yen (£4.70) an hour working in a printing factory. "If I fall really ill, I sometimes think that I might just die."

The gap between extremes of income at the top and bottom of society – the so-called Gini coefficient – has been growing in Japan for years. Inequality rose here twice as fast as in other rich countries between 1985 and 2000, according to the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development. But the gap seems to have accelerated under former prime minister Junichiro Koizumi. A supporter of neoliberal economic reforms who privatised the giant post office and cut public spending, Mr Koizumi once said he did not see anything wrong with social disparities and wanted to create "a society that rewards talented people who make efforts".

Some people took that to heart. The Koizumi era is credited with spawning a new breed of entrepreneur, typified by the brash young upstart Takafumi Horie, who built a $6bn empire of smoke and mirrors before going to prison for manipulating the stock price of his internet-services firm Livedoor.

Horiemon, as he was nicknamed, drove a Ferrari, enthusiastically blogged his expensive culinary tastes and once wrote a best-selling book called How to Make $10bn Yen, which won him legions of young fans. The opposition politician Naoto Kan accused Mr Koizumi of turning Japan in a divided society of "Horiemons and the homeless".

Horie and Mr Koizumi are gone, but the winners of that sharp-elbowed era are still with us, and they have money to burn. In the showrooms of Ginza and the upmarket Azabu-Juban in Tokyo, sales of Maserati, Ferraris and Porches that will rarely get past second gear on the city's crowded streets are up in some case by 20 per cent, even as shipments of family cars in Japan fall to their lowest level in 35 years. The Nomura Research Institute tried recently to identify this new breed of super rich, estimating that there are 60,000 Japanese households with assets of over 500 million yen (£2.3m), a number that grows every year.

One Tokyo magazine surveyed the lifestyle of the new elite and found some living on over 100m yen (£468,400) a year. The rich-list of consumer desirables included a Patek Philippe 5074 watch (41m yen, £192,000) and a 3,335 sq m apartment in Tokyo's Park Mansion Chidorigafuchi at 135m yen (£632,300). Meanwhile, sales in ordinary supermarkets and department stores have been sliding for a decade. In some cases, the rich appear to lord it over the rest of the city. The Ritz-Carlton, for example, which opened last year, occupies the top three floors of Tokyo's tallest building, the Midtown Tower, where luxury rooms with some of the "best views of Mount Fuji and the Imperial Palace" can be rented for 2.1m yen (£9,800) a night. The hotel bar's speciality is the 1.8m yen (£8,400) "diamond martini," complete with real gem.

"One man bought one for his wife," explained a spokeswoman, who said the bar had sold just two of the drinks since it opened. "It was very sweet."

Despite the gradual emergence of US-style income disparities, Japan does not have the open social sores of American cities. The ranks of the homeless are still largely out of sight and unemployment is less than 4 per cent. Millions of part-time young workers still live at home, rent free, with their parents, the generation of workers that drove Japan's postwar boom.

But the fear is that as the generation of baby boomers dies out, and the country's economic slide accelerates – Japan's share of the global economy has fallen below 10 per cent from a peak of 18 per cent in 1994 – the income disparities will really begin to pull this society apart. "There has always been an income gap here but it is the rise of poverty that is really the problem," says Kaori Katada, a sociologist at Tokyo Metropolitan University. "If this is not addressed, there will be serious social problems."

Time will tell if the authorities have the power, or will, to tackle the growing wealth gap. The Prime Minister, Yasuo Fukuda, has come under fire from the opposition, who accuse his government of fuelling the divide with reforms designed to make the economy more competitive.

"Kakusa shakai" was one of the buzz words of last year's general election and with the rival Democratic Party gunning for Mr Fukuda's ruling Liberal Democrats (LDP) he has, at least publicly, rejected a society of survival of the fittest. But the rot – if that's what it is – seems to start from the top. Official income reports released last year showed the average annual income for the 10 richest politicians was 115m yen (£538,600). Most of them are in the LDP.

None of which will bother the Hummer Owners Club, which gathers once a month for a bone-shaking cavalcade through the capital to Tokyo Bay. As the 20-car convoy trundles passed goggle-eyed pedestrians, some point while others reach for mobile-phone cameras. But not everybody is impressed.

"Bakabakashii" (ridiculous), snorts pensioner Koji Ichikawa. "Maybe they'll drive into the bay."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments