Musharraf: the legacy of the enigmatic general who became president

Pervez Musharraf was the ultimate political enigma, a military dictator who promised genuine democracy, a strongman who launched a coup in what he said was a bid to end corruption. He locked up thousands of political opponents and dissidents yet oversaw an increase in the freedom of the media and he busily rigged elections before losing power by holding a free and fair ballot. Now after almost nine years of rule, Mr Musharraf has gone. For Pakistan and the world, what legacy does he leave?

Relationship with the West

He was the man the West could do business with. He was a vital ally in the "war on terror" and – in the words of George Bush – a "strong defender of freedom". He wore well-cut Western suits, drank whiskey and enjoyed a cigar. He was recognisably "one of us". He was even prepared to appear on late-night comedy shows and be gently teased by his host.

When Pervez Musharraf seized power in a 1999 coup, there was initially consternation in the US. But just days after 9/11, Washington gave him an ultimatum: Pakistan was either "100 per cent with us or 100 per cent against us". That's when the military leader began playing a clever game with the West.

When it suited him he could warn of the threat of Islamist terror emanating from inside the country and argue that his leadership was essential not only for the people of Pakistan but for the safety of the West. Yet when he needed to reach out to Islamist parties for his own domestic political needs, he did so. Playing the role of the strongman earned Pakistan billions of dollars in military aid from the West since 2001. Moreover it ensured that he received unprecedented political support from the US and Britain, to the extent that, for many years, critics of Washington's backing of a dictator were told there was no "Plan B". He retained this support right to the end. After last February's election in which Mr Musharraf's parliamentary allies were defeated, the US and Britain urged his opponents not to force his resignation. In the past 10 days those same allies have been negotiating his exit package.

War on terror

If there is defining feature of Mr Musharraf's presidency it will be his role in Washington's "war on terror". Swiftly signing up to George Bush's project, it required a rapid U-turn in a key policy area as Pakistan's army and its notoriously powerful spies had previously enjoyed intimate links with Islamist militants.

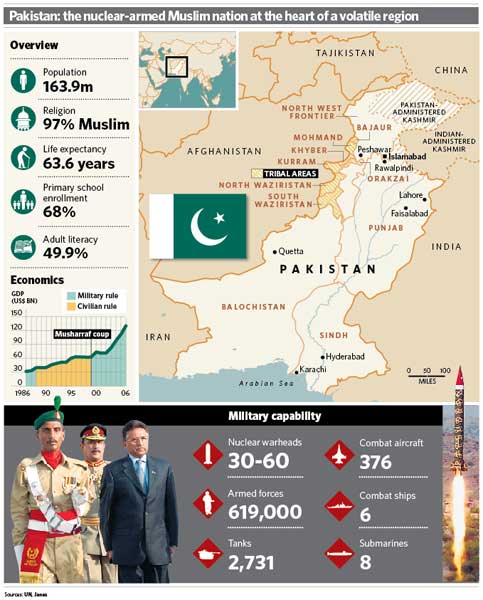

While Mr Musharraf's decision to allow use of Pakistani airspace in the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan won him few friends at home, it did bring rewards. Over the past seven years, Pakistan has received close to $12bn (£6bn) in aid – chiefly for its military. This shower of largesse, paired with the lifting of sanctions related to its 1998 nuclear tests, helped revive an ailing economy.

But it has involved grave risks. In recent years, the war in Afghanistan has spilled across the porous Durand Line into Pakistan. Al-Qa'ida and Taliban elements were introduced into the semi-autonomous tribal regions and Mr Musharraf and his regime became a target. The President narrowly cheated death twice when militants attempted to blow up his car in Rawalpindi.

Yet whatever he did, Washington demanded more. In late 2004, the army was forced to go into Waziristan, the tribal badlands where Osama bin Laden has been suspected of hiding and a local variety of the Taliban has emerged. The US army routinely dispatches pilotless drones over it and other tribal areas to collect intelligence and fire at select targets.

Today, the fall-out from the push into the tribal areas continues to shake Pakistan. A military operation is underway in the Bajaur tribal agency, where jets and helicopter gunships are targeting 3,000 militants. More than 460 militants and 22 troops have been killed, as more than 200,000 residents have been force to flee the area. The Pakistan military has some 80,000 troops positioned in the tribal areas. But their presence has come at a cost, as more than 1,000 soldiers have died.

Even recently the Pakistani Taliban have seized territory deep into the settled areas of the North-West Frontier Province. A tenuous peace holds in certain parts from a series of negotiated peace deals. But even the likes of Maulana Fazlur Rehman, an Islamist politician who once considered himself a patron of the Taliban, have begun to warn that the province is fast slipping out of Islamabad's control.

Economic policy and education

The money received from the US undoubtedly helped Pakistan's ailing economy. With the input of terror dollars, he was able to oversee a steady turn-around. During the second part of his eight-and-a-half years when growth was running at about six per cent, Mr Musharraf won the support of large segments of the business community.

Much of that support remains. As Mohammed Anis, a stationery store owner in Islamabad's Jinnah Market, said yesterday: "Business was good when he was in charge. The problems that we have now have all come under the civilian government."

Much of Pakistani society is backward and feudal and that has not changed since 1999. Under Mr Musharraf, education expenditure rose from 1.8 per cent of GDP in 2000 to 2.25 per cent in 2005. Government figures claim that, while the literacy rate in 2005 was a modest 54 per cent, compared to more than 60 per cent in India, it had risen nine points in the past five years.

Mr Musharraf always claimed he was tackling the issue of Islamic schools, or madrasas, and in 2002 announced a crackdown. But while a number of the madrasas were reformed, many of the Islamic schools continued to flourish.

Internal Democracy

If the former military commander had an ambiguous attitude towards Islamism, his relationship with democracy was also two-faced. The man who so proudly wore his military uniform always said he wanted to return Pakistan to democracy. On the very night in 1999 that he seized power in a military coup, he said he had done so with great reluctance and he wished to return the country to civilian rule. "The armed forces have no intention to stay in charge longer than is absolutely necessary to pave the way for true democracy to flourish," he said.

The reality was somewhat different. Though he talked of the three-phase transition to democracy, he was reluctant to give away the power he held as a result of his uniform and it took him until the end of 2007 to stand down as head of the army. Along the way he oversaw a rigged election in 2002 he blamed on the "over-enthusiasm" of his supporters. While the man who stamped out dissent and locked up thousands of people without charge felt able to hand over some powers to the government, that was because they were his supporters.

Mr Musharraf's downfall dates from his decision to sack the Chief Justice, Iftikhar Chaudhry, in March 2007. The move resulted in a huge backlash against a position that most Pakistanis believed should be independent. He was eventually reinstated by the Supreme Court.

Mr Musharraf was re-elected to a second five-year term by the country's lame duck parliament in October last year. But the Supreme Court said that, while the election should go ahead, it retained the right not to invalidate the decision. A few days before the court was expected to rule against him, he pre-emptively declared a state of emergency. Once again the move towards democracy took a back seat. To the surprise of most, last February's election was free and fair and it delivered a devastating blow to Mr Musharraf and his allies. Six months later, the election victors have forced him from office.

Relationship with India

For a man who participated in the 1965 and 1971 wars with India, Mr Musharraf ultimately developed a healthy relationship with Pakistan's massive nuclear-armed neighbour. While he was serving as army chief in 1999, Pakistani paramilitary troops and Kashmiri fighters crossed the Line of Control at Kargil.

The conflict did not erupt into wholesale war but two years later, by then with Mr Musharraf serving as president, Pakistani and Indian troops massed once again along the border. This time the build-up was triggered by India following a bomb attack in the parliament in Delhi which it blamed on militant groups based in Pakistan. A stand-down was only achieved after the international community intervened between the two nuclear powers.

In 2004 Mr Musharraf helped initiate a peace accord with the BJP government in India which has led to a reduction in tension.

Ironically, since the civilian government came to power in Pakistan in February, the number of cross-border incursions in Kashmir have increased. There is concern that now their former foe is gone, a weaker civilian government will be unable to exert the same control that Mr Musharraf did over Pakistan's army and the powerful ISI intelligence agency which India suspects has a hand in most attacks on its soil.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies