Tibet's Secret Temple: Wellcome Collection's new exhibition showcases the glories of Lhasa's Lukhang Palace

The images and murals that adorned the private temple of Tibet's Dalai Lamas, once glimpsed only by initiates, are now on show at a new exhibition in London. Peter Popham explores the earthly treasures of Tantric Buddhism

As a young boy, marooned in the crumbling splendour of the Potala Palace in Lhasa, Tibet, one of the Dalai Lama's great pleasures was his telescope. His bedroom was on the seventh and top floor of the palace, and as soon as his lessons were over, as he wrote in his autobiography, "I would rush out on the roof" to see what could be seen. The palace roof had "a magnificent view" and he would turn his lens in all directions, inspecting the nearby medical school, the Jokhang temple, and the state prison in the village of Shol, where the prisoners exercising in the yard "threw themselves down in prostration" when they caught sight of Tibet's most revered monk gazing down on them.

But there was another tantalising sight, closer to hand than the prison but equally inaccessible to the young boy: the Lukhang Palace, a three-storey polygonal structure, designed in the form of a mandala, a symbolic representation of the cosmos, which rose from a small lake directly behind the Potala.

Like the Potala, the Lukhang was built as a residence for the Dalai Lamas, the de facto rulers of Tibet for centuries. But unlike his vast, austere home, where he lived among mice and centuries of dust, the Lukhang was closed to him. The view from the roof was as near to it as he could get.

It had been built towards the end of the 16th century on the orders of the present Dalai Lama's most famous predecessor, the man known as "the Great Fifth", then completed during the long interregnum that followed his death. On completion it was occupied by the next reincarnation to be crowned Dalai Lama, the Sixth.

Very different from the austere yet charismatic Fifth, who did more than anyone to unify the country, the Sixth Dalai Lama seemed a bad fit for the top job. "The sixth Dalai Lama showed a worrying lack of interest in his studies," Tibet historian Sam van Schaik wrote. "As he approached adulthood, [he] became quite sure that he could not be a monk… [He] started going out at night, and was seen drinking in bars, and staggering drunkenly through the streets singing with friends."

"He delighted… in nightly assignations with girls from the town," Ian Baker writes. He would invite them to his splendid new home, the Lukhang Palace, also known as the Serpent House, which was accessible only by a rowing boat made of animal skin. There he would meet them in the long upper room "with its view across the dark water to the trees beyond."

Entirely secluded, closed to the world and surrounded by water, a more charming place of assignation is hard to imagine. And when the lovers tired of their amorous frolics, and of the views beyond the woven yak-hair curtains that shaded the rooms, the young man would have led his lover by the hand through the rooms of his home: the chapel on the ground floor devoted to the serpent-like Nagas for whom the palace had been named, the paintings on the floor above depicting the mythical adventures of an early Tibetan sage in the Nagas' underwater realm, and finally the private meditation chamber on the top floor, its walls covered with murals unlike any others in the world.

Those murals have now become, at the urging of the present Dalai Lama, the basis of a remarkable exhibition that opens in central London tomorrow.

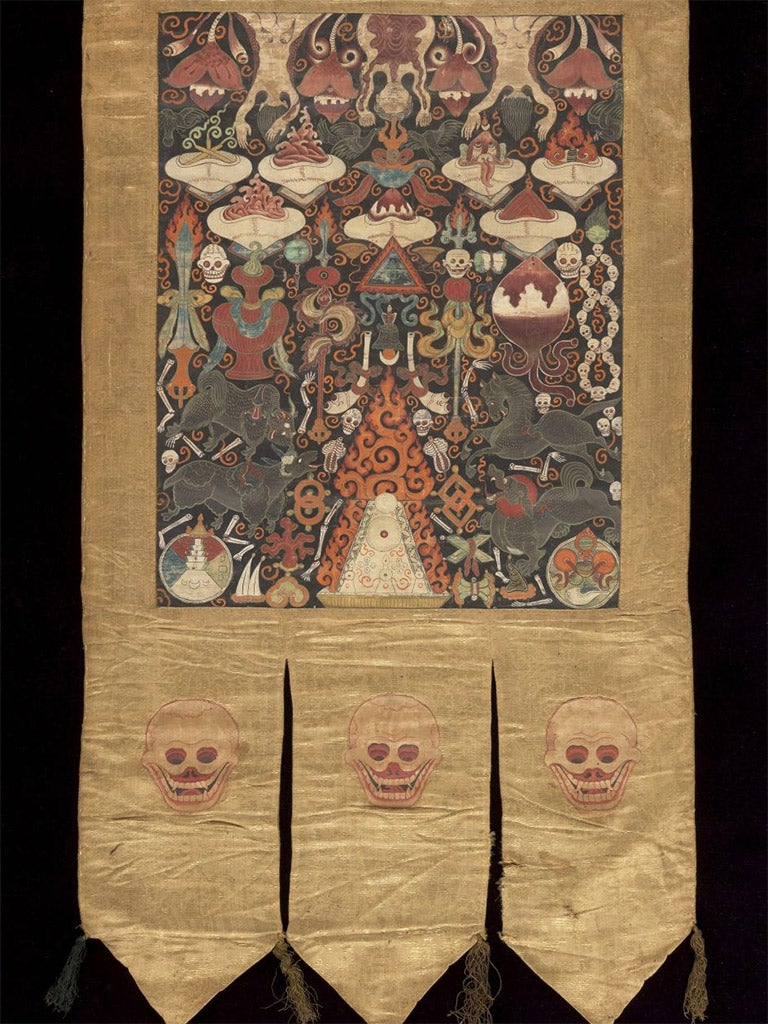

These are no ordinary wall paintings. Entering the Lukhang was to enter a world of faith and spiritual endeavour that has no parallel in the Buddhist world, and which remained unknown to the great majority of pious Tibetans; even the Dalai Lamas were only admitted to it in adulthood, after a series of initiations. Because the paintings on its walls were not decorative: they formed a series of visual instructions into the most esoteric practices and beliefs of Tibetan Buddhism.

The present Dalai Lama fled from the advancing Chinese in March 1959 when he was 24. He had yet to receive the initiations that would have opened the doors of the Lukhang to him, and he had never seen the paintings on its walls. But many years later he received a visit from a tall, sturdy young American with a thick black beard who had come to his Indian home in the Himalayan town of Dharamsala bringing a party of American students.

The young man was Ian Baker, who had already been a practising Buddhist, the student of a high Tibetan lama in Kathmandu, for some years. Under Chinese rule the formerly secret chambers of the Lukhang, which by some miracle had survived the depredations of the Cultural Revolution, were now open to tourists, and Baker went to see them. "I first went to Tibet in 1985 and started taking photographs of these things," he told me. "At that time, I was seeing the Dalai Lama twice a year because I was taking groups of American students there in groups. And I showed him photographs from the Lukhang.

"He was very excited. He had had to leave Tibet before he had had the required initiations and he had never gone to it: he had seen it from the top of the Potala with a telescope and had lived with this image of the Lukhang in the lake but then had to leave Tibet before he could visit it himself.

"I showed him the photographs and he said, 'Make a book about them.' That had never been my intention until he said it. He said these images are very important for Westerners to see. He said they would be very helpful to Westerners – more than to see images of multi-headed, multi-armed Tantric gods. He said the time of secrecy is over: the reason for keeping these things secret in Tibet no longer pertained. If we do not reveal them now, he said, they will be lost."

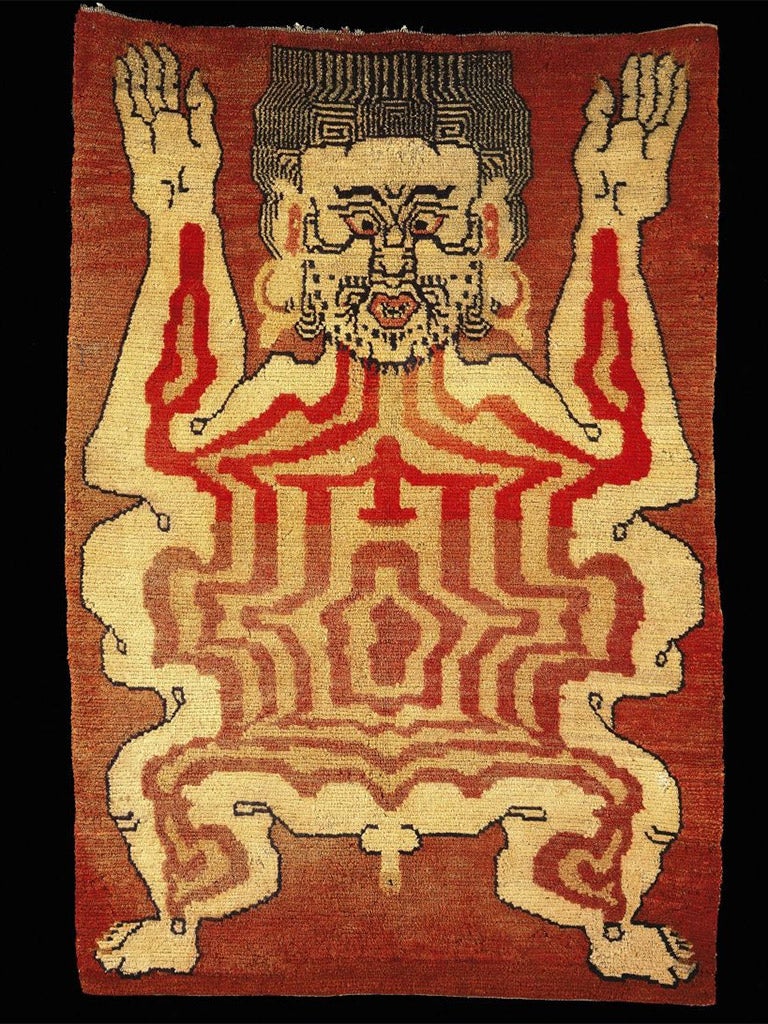

That conversation has now borne fruit. Today, at the Wellcome Collection in central London, an exhibition entitled "Tibet's Secret Temple: Body, Mind and Meditation in Tantric Buddhism" opens, running until February. High-quality, full-size digital photographs of the murals of the Lukhang, by photographer Thomas Laird, are complemented by David Bickerstaff’s film of life and devotion in Lhasa today and a quantity of objects, some very rare, borrowed from museums including Pitt-Rivers in the USA and the Musée Guimet in Paris. The exhibition culminates in a virtual recreation of the palace's top-floor meditation room.

Ian Baker, the author of highly praised books on Tibetan and Himalayan cultural history and joint curator of the exhibition, says, "It is a way of bringing visitors into a virtually created world of Tibet at the height of its artistic and cultural production at the turn of the 17th century."

The Lukhang had its origins in a dream experienced by the Fifth Dalai Lama while the Potala Palace was under construction, in which he was visited by the Nagas, the subterranean serpent spirits, who complained that the building work was disturbing them. To propitiate them, he promised to build them a temple, and projected the smaller, secluded palace that became the Lukhang, the Temple of the Serpent Spirits. It was brought to fruition by Sangye Gyatso, the regent who ruled Tibet after the Fifth Dalai Lama's death.

As Baker sees it, the pleasure-loving Sixth Dalai Lama's rejection of the trappings and restrictions of being a monk connects with the teachings by which he would have been surrounded in visual form in the Lukhang. "It wasn't that he didn't want to be the Dalai Lama," he says. "Rather, he wanted to live out the life of the Tantric adept, the mahasiddha."

Tibetan Buddhism is mostly known to the outside world through its monks, of whom the Dalai Lama is the most famous. The uniform of simple maroon robe, the discipline of the monastery with its numerous precepts including celibacy and teetotalism – these are the most recognisable features of the Tibetan faith, linking it to the related monastic traditions of Burma, Thailand, Japan and elsewhere.

But Tibet has also, from the earliest days, been home to a very different Buddhist tradition, that of Tantric or Esoteric Buddhism. Like the monastic variety, this arrived more than 1,000 years ago from India; both found remarkably fertile conditions in the freezing Himalayan plateau. But the adepts of Tantric Buddhism, the mahasiddhas, appear to have little in common with the monks: each adept, often wearing the long, tangled locks and beard of the sadhus of India, follows his own path, without the disciplines of renunciation and uniformity that are the stamp of the monasteries.

Monasticism became prevalent in Tibet, Baker maintains, "for political reasons, because you couldn't unify Tibet within the wild, freewheeling lifestyle of the Tantrics, so you had to bring back a monastic form of Buddhism." But the Tantric side was always there, it was just "hidden away", as he puts it.

"This temple documented in visual form these secret practices that otherwise were unknown to the common people except by rumour, and even to monks, who were never initiated into these practices, for the most part, because they really go against the monastic vows." So the Dalai Lama, like many other lamas, was initiated into the Tantric practices, but because some of these involved breaking the strict monastic code, the initiations took place in secret, without publicity.

But even for those who ventured deep into Tantric practices, this path was not a rejection of the moral and ethical ideas that are the foundation of mainstream Mahayana Buddhism. Baker says: "My teacher said it's like the two wings of a bird. You can't fly with only one wing: you need the ethical, moral foundation as well as the Tantra."

The murals in the exhibition cover a wide range of the activities and studies characteristic of Tantric Buddhism: Tibetan medicine, a fusion of Indian Ayurveda with Chinese traditional medicine; forms of yoga that flourished in Tibet and that are still practised by Tibetans; methods of meditation which are strikingly different from the familiar ones. They also show deities, teachers and the Buddha himself, in joyous sexual congress with their consorts.

All these practices, Baker says, have a single aim. "These paintings were made to show the quickest path to enlightenment," he says. "'Tan' in the word 'tantra' means to expand, so this wasn't about renunciation, it was about expansion. It was no longer about withdrawal from the senses; desire was no longer seen as something that was inimical to the realisation of our true potential as human beings but as something that needed to be explored and purified, to be redefined in our own experience."

But what can all this mean to the visitor walking in off the Euston Road? What is the point of immersing ourselves in such imagery? Can we obtain some benefit from them? Or are they no more than fascinating specimens of orientalist exotica? One British lama in the Tibetan tradition, himself an initiate into many Tantric practices who has been teaching them to his carefully prepared students for many years, cautions, "This is extraordinarily technical material to be used by yogins" – practitioners of 'yoga' in the deepest sense – "endowed with the ethical impulse of achieving enlightenment, a state beyond birth and death, for the benefit of all beings."

He goes on, "To make this material appear relevant to a secular audience, it has been commodified – hence the teasing stress on 'secrecy'. I'm sure the exhibition has been put together with some care, but in the end one must just ask 'Why?'"

Ian Baker replies, "What this exhibition is about is trying to show a whole culture dedicated to transforming the human condition. That's what makes it relevant in the world today. We don't have to apply these things literally, but what they show symbolically is this heroic idea that what we've inherited we can change.

"We're seeing that some of the things that get us into trouble, sexuality for example – there's another way of relating to them. Desire isn't something we have to give up, it's something we have to fully comprehend. When our passions are mobilised we discover that there is a whole wealth and possibility of joy and creativity that comes from within.

"This was a civilisation dedicated to discovering a new definition of the human condition. The exhibition hopes to be an inspiration for people to see the possibility of what can be done with human life. It doesn't give a prescription, it's not a how-to guide book, but it will point people in that direction.

"The best outcome is for people to recognise that on the other side of the world there was a civilisation dedicated to a completely different concept of what being human is all about. What we see in this world of Tibetan Buddhism is incredible diversity. This exhibition begins where a lot of yoga classes end. It's about encountering life and death."

Tibet's Secret Temple: Body, Mind and Meditation in Tantric Buddhism, Wellcome Collection, Euston Road, London NW1, from today until 28 Februrary

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments