Going, going, gone...to the light-fingered porters

For more than a century, the "Savoyards" were a closed society of Alpine villagers which monopolised portering duties at the world's oldest auction house.

French investigators have now formally accused them of becoming an "organised crime gang" which conspired to steal antique furniture and valuable works of art.

The uniformed, self-governing group of porters – recruited from a handful of villages in the French Alps – have been banned by a "judicial control order" from removal and ushering duties at the Drouot auction house in Paris which have been their exclusive prerogative for more than 150 years.

Twenty of the 110 porters have been formally accused of pilfering objects ranging from antique furniture, to diamonds, to Gustave Courbet and Marc Chagall paintings. They have been placed under investigation for "criminal conspiracy" and the "theft and receipt of stolen goods in an organised gang".

After an eight month investigation, police and an examining magistrate believe that – although many porters were honest – thefts by the "Savoyards" had become systematic. Their association, the Union des Commissionaires de l'Hôtel des ventes, has therefore also been "mis en examen" for criminal conspiracy.

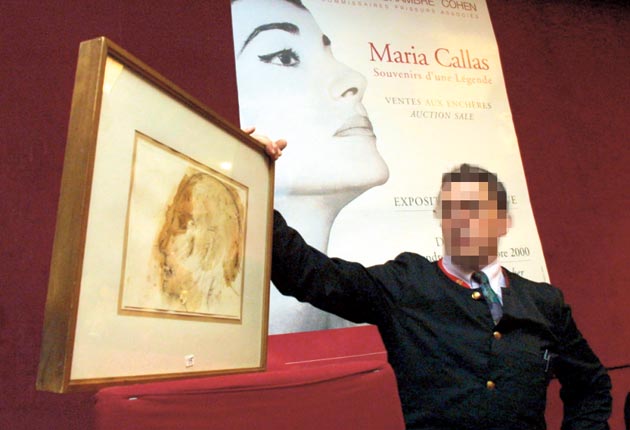

The investigation began last December after one of the porters tried to sell a painting by the French "pre-Impressionist" Gustave Courbet in the back room of a bar near to the principal Drouot auction house in the ninth arrondissement of Paris.

A series of police raids uncovered a treasure trove of allegedly pilfered objets d'art in porters' homes or in 125 large containers used by the Savoyards at a warehouse on the eastern edges of Paris. They included a watercolour by Marc Chagall, diamonds, antique furniture and ancient books.

Over 800,000 objects pass through the hands of the three Drouot auction houses in Paris each year. Not all of them, it seems, fall under the gavel of an auctioneer. It was the job of the corps of 110 self-employed, self-regulating, uniformed Drouot porters to collect items for sale. One of their most frequent – and, it now appears, lucrative – tasks was to collect all the furniture and art works left by deceased, wealthy old people.

French investigators believe that some – but by no means all – porters hid away items from large and valuable estates. If someone complained, the missing item mysteriously reappeared. If the theft was not spotted by the heirs, the items were sold privately or auctioned at Drouot after a period of months or even years. Police and art dealers say that slow-motion thefts of this kind have been widespread at Drouot for decades but have traditionally involved relatively low-value items.

Another common practice, dealers say, was for porters to steal parts of an antique in transit– such as the doors of a wardrobe – and then buy the "incomplete" article for a low price. Several months later, the item would be re-assembled and sold on for a big profit. In recent years, however, it is believed that these dishonest practices have become more widespread and more ambitious. The judicial investigation is also examining the alleged role of a handful of chartered auctioneers who are suspected of knowingly selling goods stolen by the porters or providing fake certificates of provenance.

Portering duties at Drouot have been monopolised by men from the high Alpine pastures of Savoie since the 1830s. Before the invention of skiing holidays, villages such as Tigne had to export part of their male population to the big city. The hold of "Savoyards" on the jobs at Drouot was officially recognised by the Emperor Napoleon III in 1860.

The auction house did not employ them directly but paid their organisation a percentage of its profits which was shared among the porters. Each of the 110 jobs was numbered and passed on within the same families or sometimes, more recently, sold to other Savoyards for up to €50,000 (£42,000).

With the growth of the winter sports industry, the original porter-supplying villages, such as Tignes, shared out the jobs with other villages in Savoie and Haute-Savoie. Each porter wore a black uniform, with a red collar carrying his official number. They were often known by nicknames, such as "Narcissus" or "The Sow", which also passed on from generation to generation.

Those porters who have not been accused of theft have told the French press that they expect to resume their work under a new guise in September. But the official watchdog of the French art market, the Conseil des Ventes Volontaires, says it believes that all 110 ex-Savoyards are forbidden to even enter the three Drouot premises.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies