Refugee crisis: Far-right's rise and dehumanising of conflict victims are greatest barriers to joint European action

As Europe faces the biggest refugee movement since the end of the Second World War, it is not only social media trolls using the language of infestation and invasion

For a taste of what happens when Europe draws up the barricades, you need to travel to the wrong side of the fence on the tiny Spanish enclave of Melilla. Living rough on the Moroccan side are people from both poor African nations and war-ravaged Syria – speaking about the pain of leaving children behind, torment at the hands of Moroccan police, and their hope that Europe will offer them a safe future.

Cross over three fences topped with razor wire, trenches packed with more barbed wire, risk detection by motion sensors ready to trigger pepper spray, then face the truncheons of two police forces, and two things happen. First, the refugees and migrants can die, and are often injured and horribly scarred. But the most striking transformation in the dozen or so feet dividing Africa and the EU is that men, woman and children stop being seen as human.

On the other side of the fence, near the well-tended greens of a Spanish golf course, cameras capture the attempts to cross the border. Spanish authorities release this grainy footage of dark specks streaming over the fence at night, their eyes glowing an eerie green. On YouTube, some users post comments joking about a zombie apocalypse.

As Europe faces the biggest refugee movement since the end of the Second World War, it is not only social media trolls using the language of infestation and invasion. British ministers speak of “marauders” and “swarms”. Far-right politicians call for all borders to be closed. The leaders of Slovakia and Hungary openly cite the Muslim religion of many of the refugees as a reason to keep them out. It all feeds into a discourse of “us” and “them” which has robbed the people fleeing chemical weapons, barrel bombs and Islamic extremism of their humanity – and puts at risk the very values on which the EU was founded.

“Familiar issues of xenophobia, denial, and political short-termism afflict the refugees of 2015 just as they did those of the 1930s and beyond,” the European Ombudsman Emily O’Reilly has reminded the bloc’s leaders. “But what distinguishes the European Union of 2015 from Europe in the 1930s… is our much stated commitment to the rights of the human being.”

But even after the picture of three-year-old Aylan al-Kurdi, drowned on a Turkish beach, brought an outpouring of sympathy, European leaders motivated by their histories, economies, and the strength of populist movements, bicker over the best course of action.

While Germany and Sweden open their doors to refugees, Hungary has started erecting a steel fence along its 110-mile border with Serbia. And it is not the first. Spain began the lock-out in Melilla, a territorial relic from colonial times. That border has been progressively reinforced since the early 2000s, resulting in the imposing rampart which symbolises the fortress that Europe has become.

Greece was next, erecting a fence along its 128-mile border with Turkey in 2011 when the country was in the grip of an economic crisis and support for anti-immigrant parties was rising. That sealed off the safest route to the EU just as Syria was plunging into its long and bloody civil war. So, instead, people started moving across the more mountainous frontier with Bulgaria, which also reinforced the border.

But building fences does not stop wars. People are just forced to take greater risks to find safety. So, more people took the most dangerous route: cramming into rickety vessels and crossing the Mediterranean from Libya. Last year saw a record 220,000 people attempt to cross by this route. More than 3,500 drowned. This year, hundreds of thousands have sailed from Turkey to the Greek islands, then trekked through the Balkans to try and reach a country that will welcome them with some humanity. Now, the sealing of the Hungary-Serbia border will deprive them of this route. Perhaps greater numbers will risk their lives casting off from Libya’s shores, or take more risky routes.

Thorbjørn Jagland, Secretary General of the human rights body the Council of Europe, cites reports of Syrians travelling all the way up to the Arctic, crossing from Russia to Norway: “What is going on now is pushing people over the borders to their neighbours and this is a never-ending story, so that’s why one has to have joint European action.”

Sealing borders simply fuels the human smuggling that EU leaders vow to eradicate, without keeping anybody out. The problem is such policies can be easy vote-winners for politicians keeping an eye on growing far-right movements.

Not too long ago, leaders such as Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban could count on a like-minded ally in North Africa. That was the late Libyan dictator, Muammar Gaddafi. In the summer of 2010, as the eurozone crisis fuelled support for extremist parties and migrants and refugees became easy scapegoats, Gaddafi made the EU an offer: give him $5bn a year or he would stop policing the Libyan coastline.

“We don’t know what will be the reaction of the white and Christian Europeans faced with this influx of starving and ignorant Africans,” he said during a visit to Rome. “We don’t know if Europe will remain an advanced and united continent or if it will be destroyed, as happened with the barbarian invasions.”

Despite expressing shock at the offer, the EU agreed to an assistance package for Libya and pledged to develop co-operation on migration. Then, in 2011, when the West backed a bombing campaign of Libya, Gaddafi made good on his threats and packed thousands of foreign workers – most in Libya legally – on to boats and cast them off towards Europe. For all his posturing, Gaddafi knew how to tap into old racial and religious prejudices for his own benefit. And there are plenty of forces in Europe today happy to dredge up these old hatreds for political gain.

“Xenophobia and anti-refugee sentiments are always a relatively easy way to conjure up support,” says Jeff Crisp, a former senior official with UNHCR and now a research associate at the Refugee Studies Centre at Oxford University. “The issue has been quite cynically and quite carefully manipulated by the people on the right.”

In Greece, supporters of the openly racist Golden Dawn give Nazi salutes for the camera and assault ethnic minorities. Politicians from Jobbik in Hungary make openly anti-Semitic statements, then hold their rallies in synagogues. In The Netherlands, opposition politician Geert Wilders accuses Muslims of “barbarism”.

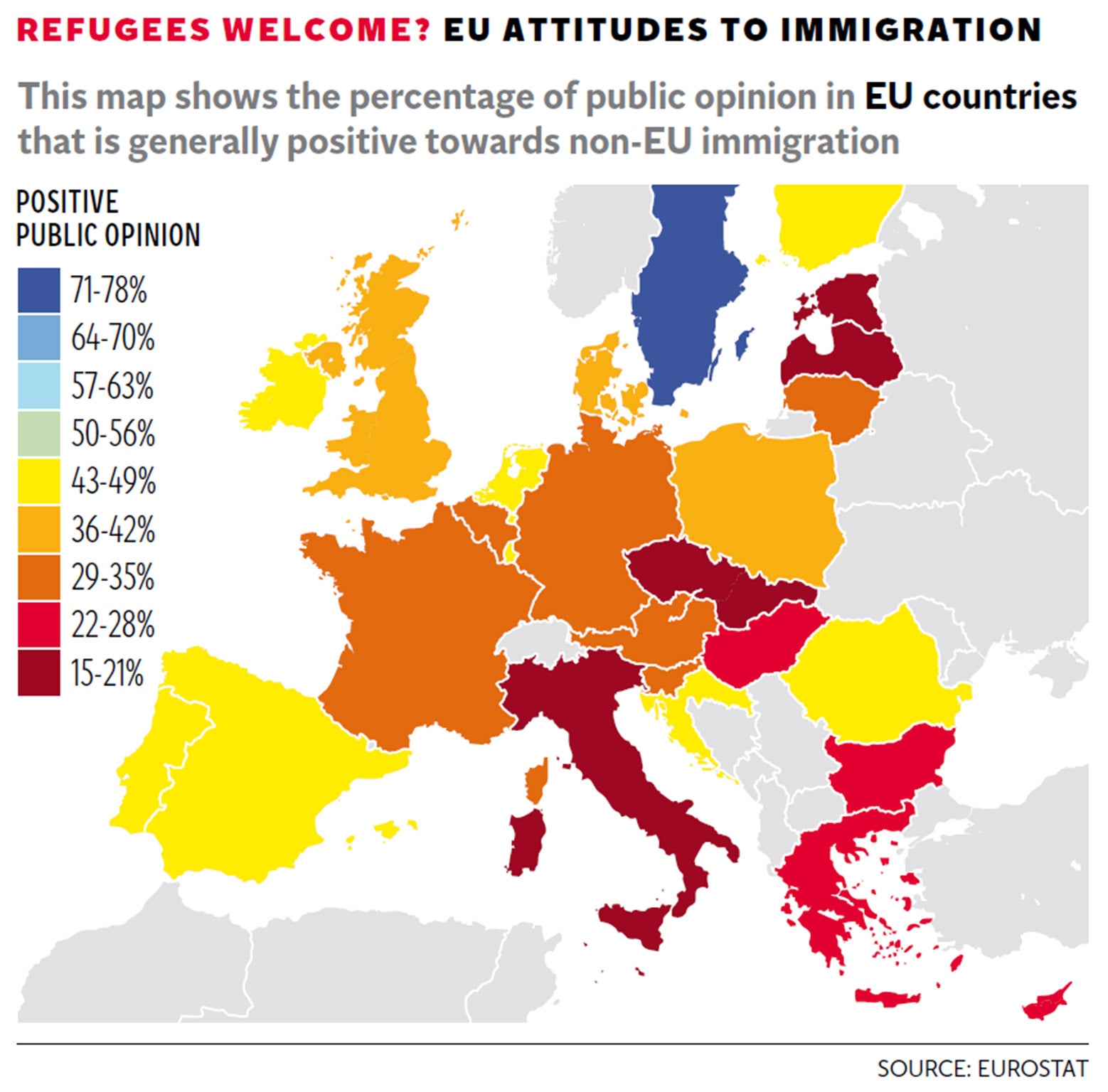

These parties do influence policy. Despite its liberal reputation, The Netherlands has some of the toughest asylum policies in Europe. In Denmark, the anti-immigration Danish People’s Party is now in a coalition government and the country has recently cut benefits to recently-arrived refugees and taken out adverts in a Lebanese newspaper warning Syrians not to expect a warm welcome. In Britain, the government has refused to take part in any EU-wide relocation scheme for Syrian refugees.

This month, EU leaders will have to decide whether or not to back binding national quotas for resettling Syrian refugees – a move most people working on refugee issues agree will help save lives. It remains unclear if the opposition from the Eastern European nations will scuttle the latest effort to forge an EU-wide policy rooted in humanity rather than security. Instead of jumping on the populist bandwagon, Mr Jagland says mainstream politicians should stand up to the hatred and explain the European values. “If one is running after these radical forces then they will win. You can never catch up with them.”

And if the xenophobic forces are able to drive the policy of the bloc, it threatens the EU’s cherished reputation as a haven of human rights.

Majid Hussain was one of the thousands of people Gaddafi forced to sea in 2011. He fled Nigeria when he was 15-years-old after seeing his father killed by a Christian mob. He had been trying to rebuild his life in Libya when he was cast off in the Mediterranean. After two days at sea, he found himself in Italy, which welcomed with a strip search before shuttling him between cramped refugee camps. After a two-year wait, he was granted asylum.

“Here is the democracy that people are dying to have – this is democracy where nobody respects you, you don’t even have dignity,” he says.

His faith in Europe was somewhat restored when he came into contact with citizen movements providing support, and he has found friends among Italian lawyers offering their services for free and the young people helping him find cheap accommodation.

It is movements like these – citizens opening their homes to refugees, crowds at railway stations applauding the Syrians in their march to safety, the hundreds of thousands of people signing The Independent’s petition urging a more humane response to the crisis – which give both Mr Crisp and Mr Jagland hope that Europe is re-discovering its values.

While Germany has seen neo-Nazis marching in the streets, Chancellor Angela Merkel has refused to shift her policy of an open door to all those seeking sanctuary. In France, where the Front National has growing support, President François Hollande has reversed his position and is now supporting EU-wide quotas. And David Cameron has agreed to accept 20,000 Syrian refugees.

“European and British asylum policy... has essentially been overturned by refugees themselves doing their own thing saying we’re not going to stay in Budapest… and by the shifting of public opinion,” says Mr Crisp.

Time will tell if the policy shifts are lasting, but right now Fortress Europe may be lowering the drawbridge a little.

Tomorrow: Robert Fisk examines the crisis in the context of the great migratory waves of history

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments